She’s telling me that she wants to add mold and fungus to my wood floors? I must not be hearing this right! But apparently Oregon State University professor Sara C. Robinson thinks this could be the future of color. I think we need to know more about this new green (and blue and yellow and red…) technique of adding color to the world around us.

Sara, are you actually asking us to put fungus into our wood dyes?

Not just wood, but textiles, stone, glass, paper, wallpaper and so much more. If it can be colored with synthetic dyes, we can color it with fungal pigments, too. Traditionally, naturally occurring pigments haven’t been as colorfast or as easy to produce as synthetic pigments. But this special grouping of fungi makes colorfast pigments in sufficient quantities to compete with synthetic dyes. Bonus: They don’t require the use of petroleum to make and are applied without water, completely eliminating waste water runoff produced by dye industries. And the extracted pigments don’t contain any fungi, so people don’t have to be concerned about anything living in their pigments.

How in the world did you get into this?

I first became seriously interested in woodworking in junior high school, during my mandatory 7th-grade shop class. My interest continued through high school, where I took every available shop class (sometimes twice), and even cut other classes to go to the shop.

Early on I focused a lot on furniture. But my senior year my teacher introduced me to bowl turning, and instantly I was hooked. After a few months he brought in a box elder piece for me to turn. The wood was streaked through with bright red and pink coloring, and I found it enchanting. The red stain of box elder wood isn’t actually spalting—that is a color caused by the tree itself. But of course I didn’t know anything about any of this at the time. I just knew it was beautiful and I wanted to do more of it.

In college I specialized in wood turning and began to specifically seek out colored woods to work with. Most of the time this manifested in heartwood/sapwood color mixtures, but occasionally I would stumble across something more colorful.

I moved into wood science from wood art and design for my master’s, with the hopes of gaining a better understanding of the material I worked with. When I needed a research project, my advisor, Peter Laks, asked me what I was interested in. I still had that box elder bowl from high school (which by then had faded from bright red to light pink) so I brought it in a showed it to him. He asked me what caused the color and I confessed that I had no idea.

It turned out, after doing some reading, that most people didn’t have any idea about the causes of spalting, or even how to define spalting. The word was both nebulous and colloquial, and very little work had ever been done to determine just which fungi caused the color in the first place.

OK, define “spalting” for us please—what is it and what causes it?

Spalting has traditionally been defined as color in wood caused by a fungus or fungi. We’ve been broadening the term recently to include any fungal colorants that readily penetrate porous and semi-porous materials. The definition has to be somewhat specific, since there are many, many fungi that make extracellular pigments, but few actually make pigments that penetrate into wood. It is this difference that makes spalting fungi more commercially viable than mold fungi like Penicillium species, as the pigments released from spalting fungi are meant to deeply penetrate and persist in the environment.

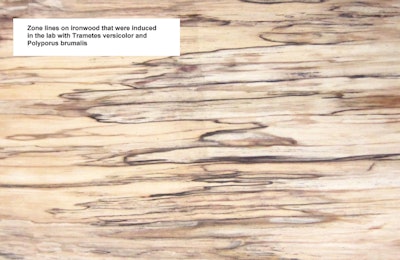

Spalting is generally broken into three main types: the bleaching or “white rot” done by basidiomycete and some select ascomycete fungi, the zone lines (commonly referred to as “black lines,” which is a misnomer since they aren’t always black) caused by changes in environmental conditions or inter/intra fungal antagonism (this is MY wood, you go away!), and the pigments, mainly extracellular (blue stain is an exception), that are released by the fungi into wood to “hold” the wood against other fungi (most fungal pigments have some antifungal properties).

With very little science training up to that point, I decided that understanding spalting, specifically the fungi responsible, would be my research goal for my master’s degree.

I think of spalted maple, and always thought that “spalted” was just a black color.

That’s the dominant type of spalting, what we call “zone lines.” My first research was looking at which fungi could be paired to get the quickest, most prolific black lines on wood.

Amazing. We’ll draw a line (pun intended!) here and pick this up next week!