Underlayment may not be the most exciting topic, but when you're a wood flooring installer, it's an important part—or should be an important part—of your daily life. As an installer years ago, I had builders literally yell at me because I did not have enough red rosin paper to complete a closet on a finished second floor! As an inspector, I've been involved in many horror stories where the wrong underlayment (or no underlayment) was used and the installation resulted in a huge, expensive mess (more on that later). If the contractors had understood how to use underlayment correctly, and which ones to use, the problems would have been avoided.

A quick journey through underlayment history

Over the centuries pros have used what was available as underlayment. Many of the first builders/carpenters who emigrated to America were actually ship carpenters and sawyers who worked with whatever was on hand, and many builders used wide planks as subflooring and even as the floor itself. Newspaper was invented in the 17th century and became popular as an underlayment in the early 19th century. Newspaper could help prevent dust from dirt cellars and crawl spaces, as well as damp, stale, moldy air, from coming up into the living area. To this day, contractors tear up old flooring and find newspapers. I worked on a house that was rebuilt after a fire in 1865, and when I did some patching of the flooring in the barn, I found dozens of newspaper pages. One actually had an ad for hardwood flooring for 39 cents a square foot! (I wish at the time we had iPhones; I never got a photo, and my partner threw the paper away.)

Around 1800–1850, we started to see rolled organic fiber materials, or what we call "rosin paper" today. Rosin paper became the underlayment staple of our industry for many years until the next generation of underlayment, asphalt paper. In reality, rosin paper did little more than newspaper: It kept down dust but did nothing to retard moisture migration. (Keep in mind that the modern luxuries of complicated heating and air conditioning systems were nonexistent; there was little concern for what happened once the hardwood flooring went down.) Rosin paper came in rolls, so it was simply an improvement on newspaper and brought additional sales to the local suppliers while making installation quicker for the installer. It's only in relatively recent years that rosin paper sales tapered off significantly.

In the 1900s, manufacturers created organic fiber "kraft" papers. Most were saturated with asphalt (tar) and called ASK paper: asphalt saturated kraft building paper. This was the first step in the fight against moisture and its potentially negative effects on wood products.

Soon to follow and basically eliminating organic paper was inorganic (a variety of stranded fiber materials not from plant material) asphalt saturated felt—what we now call 15 pound (#15 class 1) and 30 pound (#30 class 2) Grade D moisture vapor retarders. Many gymnasium installers, concerned about moisture migration, would use hot roofing tar or adhesive to glue layers of this "black felt" over concrete prior to laying screeds/bunkers/sleepers and then hardwood flooring (mostly 33/32-inch hard maple strip).

RELATED: 5 Wood Flooring Installation Sins

Today we have many options for wood flooring underlayment. Instead of worrying about the filth from the basement migrating up through our wood floors, our primary concerns are moisture and sound control. We all know wood and water don't mix and "squeaks make squawks." Also, a floor that absorbs or reflects sound can be a massive issue—and even a legal matter!

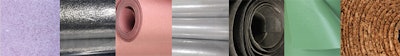

Our modern underlayments are manufactured using many products and recycled materials including: high-density polyurethane foam, nylon and polyester fibers, soybean, polyol, vegetable oils, closed-cell polypropylene, wood fiber and plastic composites, and polyethylene film (6-mil is common). They may combine different materials, such as breathable fiber with a plastic membrane. There has been a move toward inorganic, recycled and more efficient materials as organic waste materials such as wood fiber have become more valuable in the production of other items.

Each underlayment manufacturer will be quick to point out the features and benefits of their particular products—and we would need to write a novel to cover them all!—so let's focus on what is important for today's hardwood flooring installers: moisture and sound. Today's underlayment manufacturers focus on both moisture and sound issues in a very scientific and calculable way.

The 411 on moisture and underlayment

First things first: Moisture! Nothing and I mean NOTHING will mess up a hardwood floor (even existing floors) more than water. Water vapor, ice, snow, standing water, running water … the wetter it is, the worse things get. We have all heard wood is "hygroscopic," which basically means wood is a sponge, swelling with the introduction of moisture and shrinking with the loss of moisture. (In case you underestimate that, consider that ancient cultures would dry wood in the hot sun, hammer the wood into cracks in marble cliffs, pour water onto the wood and use the mountains of marble that would come tumbling down—that is how strong swollen wood can be.)

The primary concern with hardwood flooring is an uneven passage of moisture from below the flooring, traveling upward and causing the floor to swell or even lift. The point of modern moisture underlayment is either to slow down or minimize moisture (today we call products that do that "retarders") or block the moisture entirely (we call those "barriers"). Totally blocking water and moisture is possible using plastic or rubberized materials, membranes and sealers, although in most cases with wood flooring, we want to slow down moisture, not block it entirely. We don't use plastic against untreated wood components where there is the potential of trapping excessive moisture in the subfloor.

Of course, WFB readers are well-versed with the concerns and issues that arise when wood and water collide, and you are also familiar with the tools for measuring moisture in the wood and in the air (see my recent blog post about my inspection tools for more on that). Here are the basics you need to understand when looking at "moisture retarder" underlayments.

Understanding permeability

Simply put, permeability is the rate at which moisture transmits through a membrane. That rate is measured in "perms," telling us how much moisture can pass through a membrane in a 24-hour period. The lower the number, the better the performance for retarding moisture migration.

RELATED: How Inside Air Affects Wood Floors

There are four classes to keep in mind when protecting hardwood flooring from possible moisture-related issues:

Vapor impermeable: 0.1 perm or less

Vapor semi-impermeable: > 0.1 – 1.0 perm

Vapor semi-permeable: > 1.0 – 10 perms

Vapor permeable: > 10 perms

Which class of permeability do you need for the wood flooring you're installing? Your best option is to ask the wood flooring manufacturer what is required, taking into consideration the flooring, subflooring and conditions for the installation. If you're installing a floating floor, the manufacturer will recommend specific underlayments. If you're installing on a second story of a home where you don't ever anticipate any moisture issues, you might be able to use red rosin paper just to make installation easier, but in most situations it's likely you'll want something that offers more protection.

Need-to-know info about sound control

Let's look at the concerns with sound control, which seems to be growing in importance for many hardwood flooring contractors. When you're dealing with sound control, there are a few terms you must understand:

IIC: Impact Insulation Class: It measures how much sound is dampened upon any impact—in our case, the impact on hardwood flooring, such as footsteps or something dropped. It is measured in decibels (dB) for sounds with frequencies between 125 and 4,000 Hz (most sounds in our daily lives). The higher the IIC rating, the more vibration is absorbed by the material. Low-rated materials come in at about 25 dB; and high-IIC underlayments can be 85 dB and higher.

STC: Sound Transmission Class: This measures how much airborne sound is absorbed. Think stereo music, the neighbors yelling, etc. It is also measured in decibels.

The list below tells you how much protection to expect at different levels:

25: Normal speech easily understood

30: Normal speech audible but not intelligible

35: Loud speech audible and fairly understandable

40: Loud speech audible but not intelligible

45: Loud speech barely audible

50: Shouting barely audible

55: Shouting not audible.

An IIC/STC of 50 is required by the International Building Code; levels reaching 70 can be considered virtually soundproof.

Delta IIC: This is the total IIC performance gain once you add your underlayment. Note that the ASTM test for this doesn't compare your flooring to what the level is with added underlayment—it compares flooring with the underlayment to a 6-inch slab without anything on it.

These sound transmission ratings are important when meeting construction codes for sound transmission, especially in multi-floor dwellings such as commercial buildings and condominiums. Violating any defined sound limits can literally cost a contractor millions of dollars. I inspected a project where many million-dollar-plus condominiums did not pass sound control parameters. Tenants had to be moved out until specifications were met. That included moving personal belongings and housing the tenants; you can imagine the expenses this debacle incurred.

Keep in mind that the biggest contributing factor to sound control is the floor-to-ceiling assembly and materials used by the builder; underlayments are just one aspect of that entire assembly. On a related note, a product with a high IIC in the lab won't necessarily perform with that high IIC in real life—it depends on the materials and construction used.

As a general rule of thumb, an IIC and/or STC rating of 52 dB is commonly acceptable for a wood floor underlayment. Hardwood floors by themselves often have an IIC of 30–40 dB, so when you add a legit sound-control underlayment you should usually have acceptable sound levels in the condo—and happy neighbors who aren't contacting their lawyers.

Old-school underlayments like newspaper, red rosin paper and asphalt felt are insignificant as far as sound transmission is concerned. Cork underlayments that are 6-mm (1/4") thick have STC ratings around 54, and the most common sound control underlayment products (2 mm–6 mm) in our industry today have IIC and STC ratings ranging from 50–74.

Though sound evaluations when installing hardwood flooring may not come up as often as moisture control, it is extremely important to be aware of the concerns with sound migration. For wood flooring contractors who want to expand their business to profitable commercial projects, understanding sound control is of utmost importance.

Whether for sound or moisture control—or both—the selection of the right underlayment product is critical to the performance and comfort of any hardwood floor installation and can even result in additional profit for the flooring contractors. On every job you do, pay attention to the flooring environment and the potential variables, and construct a flooring system that will perform well for everyone involved.

Perm ratings of common underlaymentsHere are the perm ratings for some underlayments that have been commonly used. Of course, modern brand-name vapor retarders have their own ratings; most will fall into the semi-impermeable range. LVT: 0.05 Rubber: 0.05 6-mm cork: 0.05 6-mil polyethylene plastic sheeting: 0.06 Silicone vapor paper (without nail holes): 0.46 Silicone vapor paper (with nail holes) 0.712 #30 asphalt felt paper: 1.75 #15 asphalt felt paper: 5.0 Kraft building paper: 5.0 Red rosin paper: 5.0 |

Common underlayment mistakesFor sound:

For moisture:

|