Wood floor work comes in a lot of different shapes and sizes these days. What my dad and others of his generation offered has gone through some dramatic transitions from the standard nail down product that was then sanded and finished. Some segments still remain the same, but the complexity has been driven by market changes from consumer demand. I never got caught up in much of that, and for most of my 45-year-career I've been drawn to old floors. For the last 25 years of my career, I've become even more focused, and this has led me into a niche market: the preservation and conservation of old wood floors. Some of these projects may appear prestigious and carry some gravitas, but the opportunity for failure and/or disappointment is even greater if you're not diligent.

The condition of dining room floor shows original finish on left side next to stains/finishes added within the last 30 years.

The condition of dining room floor shows original finish on left side next to stains/finishes added within the last 30 years.

The dining room floor after the center section was cleared of original coatings.

The dining room floor after the center section was cleared of original coatings.

This closeup above shows the original coating (on the left) beside wood cleaned of all surface accumulations without sanding.

This closeup above shows the original coating (on the left) beside wood cleaned of all surface accumulations without sanding.

One of the things that distinguish my business from others is that we restore wood floors without traditional aggressive sanding. Everyone in the wood flooring business knows that with each sanding, you lose valuable mass and weaken the surface. There's no denying it, and that is why aggressive sanding is the bane of history professionals. Like me, history professionals understand that the wood floor in any old structure is the only surface that loses mass and is weakened while it is being "restored." I wanted to change that, and I hope I'm having a positive impact.

The system I use is a radical departure from the standard approach and requires a very different mindset from the get-go. It takes longer, materials and labor costs are higher, and it is fraught with curves and variables. My most recent project is a good example; it gives a good overview of how I approach these historic restoration projects and how they differ from the traditional sand/stain/finish work I started with in 1973.

One of 14 samples done to ensure the old coatings could be removed with chemicals.

One of 14 samples done to ensure the old coatings could be removed with chemicals.

Introducing Fair Lane

Historic Ford Estates (HFE) oversees two Ford properties: Henry and Clara Ford's estate, Fair Lane, in Dearborn, Mich., and Edsel and Eleanor Ford's estate, Gaukler Point, in Grosse Pointe, Mich. HFE recently acquired Fair Lane, and the home of America's most iconic industrialist was in dire need of a lot of preservation work. They contacted me in 2015, and after several months of phone calls, emails and texts, a plan started to formalize.

The estate backs up to the River Rouge and was completed in 1915 just as war in Europe was erupting. It's fairly large and comes in at about 32,000 square feet, with a little less than half of that being wood floors. Henry and Clara lived in the house until their respective deaths in 1947 and 1950. The house then passed into the hands of Ford Motor Co. for a short period of time and was passed on to the University of Michigan–Dearborn. The home having been under institutional care (Ford Motor Company and the university) for about two-thirds of its life had a huge impact on how the floors were maintained and what had accumulated on the surface of the floors.

As with all my restoration projects, I made an on-site visit to evaluate the floors, perform tests/sampling and see the scope of the project. I always do extensive documentation and, thanks to digital cameras and smartphones, it's a much easier process than it used to be. If there's archival information available, I jump right into that, as well, and fortunately HFE had reams of documents and photos to work with.

Due diligence & devilish details

Testing and sampling is critical to ensure that my approach to preserving the old wood floors will work. I use a process that relies heavily on non-toxic, biodegradable chemicals to put the old finishes back into a solution so they can be removed. This approach allows me to totally avoid any traditional aggressive sanding and addresses the main concern of history professionals: loss of original material.

For my initial two-day visit, I performed 14 test samples (see the photo at right) on the first and second floors to ensure I wasn't going to stumble onto discoveries that would sidetrack my crew and me once we were in full swing. This may sound excessive, but the number of iterations of finish applications and accumulation of who-knows-what you are confronted with on these historic floors can set your head spinning.

The 900-square-foot living room had multiple layers of finish and maintenance products around the perimeter. The dining room and billiard room were similar but included sections where the university had ground down borders to apply stain and more finish. The long upstairs hall not only had the original finish, but on top of that it had multiple layers of heavily tinted finishes to the point that much of the wood was totally obscured. I devoted significant time and effort to identify pre-existing damage that lay just under the finish, hidden from sight.

The dining room after all coatings were removed and hardening oil applied.

The dining room after all coatings were removed and hardening oil applied.

Other complicating factors

When you step back and look at the work environment, you realize there are other complex issues. Security, equipment and materials storage, and visitor tours need to be factored into your plans. But that's just a start.

Take electrical power, for example. Are the few outlets available grounded? Will the 100-year-old power grid support your equipment and accessories, and how do you get more power should you need it? Do you need Google Maps when a breaker or fuse gives out?

The billiard room after all coatings were removed and hardening oil applied.

The billiard room after all coatings were removed and hardening oil applied.

Looking down the grand staircase at the walnut/oak herringbone stair treads.

Looking down the grand staircase at the walnut/oak herringbone stair treads.

Lights are another little "gotcha" you want to consider. Big houses tend to be dark inside, so you often need to bring/create your own light source. You would be wise to avoid halogen, as its heat and power demands could spell trouble. You can also forget about using clamp lighting since you'll be the one clamped if a curator walks through and sees your light hanging onto doors or window trim.

Finally, let's cover a subject near and dear to me … access to bathrooms. Of the umpteen original bathrooms, guess how many are operational (and none close to where you're working). The only positive aspect of having a bladder like mine is I easily get my 10,000 steps for my Fitbit.

Once my initial visit was done, I had the information I needed to focus on three main areas: preparation of a proposal, worker and materials logistics, and the all important pre-restoration meeting with the other artisans/trades and principals. The first two items aren't much of a challenge for me anymore, but the pre-restoration meeting needed all the diplomacy I could muster up. I was focused on putting us at the front end of the scheduling (see my article about that, "Why we're never the last contractor on the job anymore"), so I went prepared with plenty of photos and documentation from other projects. There's definitely a cost factor in covering and protecting finished floors, but it's the flexibility for scheduling on the back end of a project that justifies the expense. My argument was convincing, and they agreed to put our work out in front of all the other building trades and artisans.

Starting up and keeping up

Work began in earnest in the summer of 2016. I already knew the work would require multiple phases, so we divided the house up according to a variety of priorities. The first two phases attacked all the downstairs public areas, the one long central hall on the second floor, and the large grand staircase and landings. This would also free up much-needed traffic routes once the refinished floors were covered and protected.

After this, we moved our operations onto the second floor into the private areas. These included family bedrooms, guest bedrooms, dressing rooms, servants' quarters, storage rooms and multiple connecting halls. This would require two separate phases and a lot more detail work in the smaller rooms, closets and hallways.

The last two phases focused on recreational areas in the main house and a detached building that housed Ford's own hydroelectric power plant, his personal laboratory, garage and furniture restoration room.

We were biting off chunks of areas that averaged about 2,200 square feet per phase, and we had enough experience to know what our pace would be. Each phase averaged two weeks, with the second phase being the exception: It came in at three weeks due to a surge in repair work. All totaled, we were looking at about 2,200 man-hours divided up between the crews.

I'm proud of my core group of workers. My younger brother, David, has been on all my major projects and besides myself, is the only other one with a background in wood floors. Peter Eiland is relatively new to my group and has exceptional broad-base woodworking skills. He was interested in the chemical removal, and I trained him prior to taking him on-site for big projects. Joseph Hurd approached me at a preservation meeting and expressed an interest. He's a rising star in my crowd; he has the work ethic I want and will listen. I still have a few others I can pull into a project if I need them, and they are scattered around the Southeast.

Regardless of how detailed your original inspection and testing are, you will always make discoveries and encounter changes in the plans, and Fair Lane was no exception. We found much more damage when areas were emptied of furniture and carpets were removed. HFE was given a proposal with hard figures for the removal of old finishes and application of new finishes, but the repairs were done on time and materials. The difficulty wasn't so much in the additional cost but in procuring materials. The dominant species was quartersawn white oak laid in a herringbone pattern. Although the pattern was the same, the lengths of the wood in some rooms varied.

The complexity of the repair work peaked with a temporary elevator shaft opening on the large landing (see the sidebar below); it was installed when the Fords became too feeble to navigate the grand staircase. It was not original to the home, and it had to go. David and Peter took on a repair that defied anything I'd ever seen: two merging herringbone patterns had intersected at a right angle, and all prior installation evidence had been removed to accommodate the elevator shaft. They had no blueprints or spec drawings as guidelines, and it was the only point in the entire house where the herringbone pattern intersected at a right angle. This was way over my pay grade, and I watched in awe as they removed steel angle iron framing in the elevator shaft and then methodically reconstructed the pattern. It is hands-down the most impressive repair work I've seen in my 45-year career.

The other major deviation came late in the project when we were asked to restore the bowling alley floors. The maple flooring that framed the bowling alley had been refinished within the last decade, and the chemicals I use had no effect on the contemporary coating. I wasn't surprised, so I did have a plan B, as in Super Bee. On the few occasions where I've needed detailed and controlled sanding on restoration jobs like these, the Super Bee and/or the U-Sand is my weapon of choice. You can easily control the loss of original material and not compromise the preservation intent. It is a superb piece of equipment, and is now the only major sanding device I have in my stable.

The leading characters in this six-act play (left to right): Joseph Hurd, David Purser, me and Peter Eiland.

The leading characters in this six-act play (left to right): Joseph Hurd, David Purser, me and Peter Eiland.

Preparing our past for the future

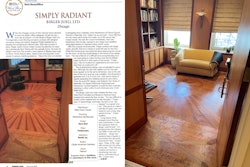

The sixth and final phase was completed in spring of this year. With the exception of the small area of maple flooring in the bowling alley that got selective sanding, the remainder of the 14,000 square feet was restored without sanding. Finish selection for historic preservation projects often follows different guidelines. The selection isn't being made for a private residence but for a high-traffic museum. The history professionals won't deviate too much, but they are sensitive to environmental concerns and original intent. They also pay a lot of attention to the long view of maintenance and refurbishing, as they should. The bowling alley had a finish applied, Bona's Mega HD Clear, and all the other floors were finished with a hardening oil, Pallmann's Magic Oil. By eliminating aggressive sanding, the finished floors have a more rustic look. The removal technique allows for slight height variations, highlights the grain of the wood and gives the wood a supple, worn-leather look.

It's my understanding that this is one of the largest and most significant restoration projects of this type going on in the country today. It's getting a lot of attention and even brought the film crew of "This Old House" on-site on our very first day of work back in 2016. I've been told the museum will likely be opening to the public around 2020. If you're in the area, your time will be well-spent touring the estate.

We've been involved in about a dozen large, high-profile restoration projects, and I cannot overemphasize how important it is to maintain a constant line of communications with the overseers during the project. History professionals are not a hard group to work with, but they often are working with a set of parameters that forces them into areas that are unfamiliar to everyone. They're tasked with projects that would be challenging under the best of circumstances (and the best of circumstances rarely happen!). I've found it helps to keep an open mind instead of trying to cling to old habits. I often talk about an issue with principals, but I always write an email summary for documentation to help everyone. There's no one set formula for all of this, and it is constantly reshaping itself to meet the project's needs, so if you are chosen to tackle a project like this, you'll need to adapt and show them flexibility, as they often have to do the same. It can get challenging, but when you combine fluid communication with a well-experienced group like my people, it always has a better ending than you thought possible.

|

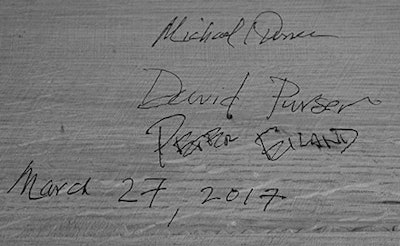

Leaving Our Own Mark in a Historic Home

We had to replace a badly damaged stair tread that stepped down into the Music Room. We sourced the quartersawn white oak from Stratton Creek Wood Works LLC in eastern Ohio, and Peter Eiland glued up the boards at his shop in Atlanta. Once we were on site, Peter and my brother, David Purser, cut out the tread (they were able to use the old tread as a template). They did a masterful job, and it fit perfectly the first time they slid it into place. We were all feeling pretty good about things and decided to leave our own mark on the history of our work by signing and dating the back of the tread before it was put in place permanently. |

The Trickiest Repair I've Ever Seen

These remnants of a patch were over an elevator shaft on the stair landing. The elevator and the subsequent patch were not original to the house, so the wood floor had to be restored to its original condition , although we didn't have the original plans showing how it came together, and this was the only place where the herringbone patterns intersected at a 90-degree angle. Peter Eiland had to begin repairs by removing the angle iron used to frame in the opening. (Read more about this repair here.) |

Get a tour of the project from Michael Purser in this video:

Other WFB articles by Michael Purser:

The Low-Hanging Fruit: Old Floor Refinishing

The Floor Listener: Wood Floors Have Stories to Tell

Take Caution When Doing Restoration Work

The Missing Link: Are You Skipping a Step in Your Recoats?

What the Wood Flooring Industry Can Learn From the Tower of Babel