Editor's Note: This is the second of our three-part series on How Wood Floors Are Made. The December/January issue dealt with forestry and lumber milling. This article details the production of solid, unfinished wood flooring. The April/May issue will cover engineered and prefinished flooring.

By the time lumber is on the verge of being milled into wood flooring, it's come a long way in the process — from the carefully managed forest through the manufacturing at the lumber mill and the kiln-drying on site at the flooring mill. Taking it from that point to solid, unfinished strip or plank, tongue-and-groove flooring is a process that hasn't changed a whole lot since the industry's beginnings.

As it enters the mill, the lumber has been kiln dried to tight specifications for moisture content, typically a specific level between the recommended 6 to 9 percent moisture content. Some mills spotcheck the lumber through an electronic moisture meter; others check the flooring at a later point.

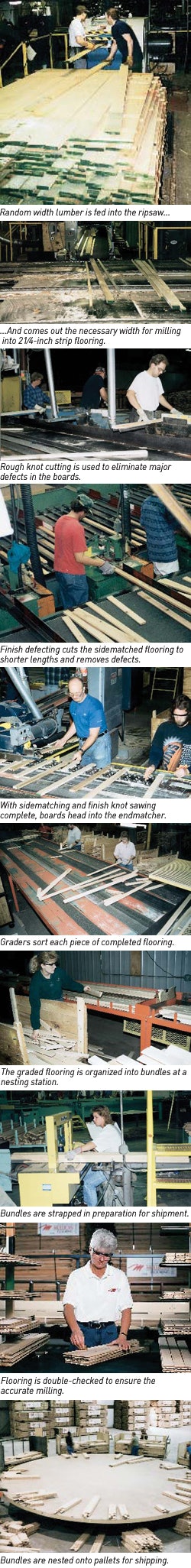

To produce 3/4 -inch flooring, the lumber is random width and 1 inch thick. In the first step of the milling process, the lumber proceeds down a conveyor and is fed into a rip saw, which cuts the flooring into blanks of the desired width (for 2 1/4 strip flooring, the blanks would be cut to — depending on the mill — 2 9/16 inches wide). Some mills use optimizing rip saws, which determine the best yield for each individual board. The edgings that result from the rip saw are often used to create moldings, narrow-width strip flooring or parquet flooring. Sawdust created from this and the rest of the milling process is often used to fuel the dry kilns or heat the mills.

Once the blanks are the desired width, mills use a rough knot saw to cut out major defects — such as large, broken knots or shake — that can cause trouble in the planer and sidematcher.

Some mills also use a preplaner, which planes the boards down to an approximate thickness of, for example, 15/16 inch. Both the rough knot saw and the preplaner make the job easier for the sidematcher, which both planes the board to its final thickness and creates the tongue and groove on each long side of the board. Each individual board is examined before it is fed into the sidematcher. Because the flooring is run upside-down, the best face of the board is put facedown.

After the sidematcher, the finish knot saw cuts out major defects that remain and also cuts extremely long pieces down to standard lengths. Cutters must carefully choose where cuts will be made to achieve the best value from each board. Next, a run through the endmatcher leaves the flooring with tongue-and-groove ends. The now-completed product is ready to be graded.

What grading means depends on the mill where the flooring is being produced. In general, grading sorts flooring of similar characteristics together — NOFMA Select oak will have fewer character marks, while No. 2 Common will have many more.

Even though flooring is separated into grades, that doesn't ensure that the flooring will have a uniform look. If the mill is a member of an association such as the National Oak Flooring Manufacturers Association or the Maple Flooring Manufacturers Association, the graders are trained according to those standards. If it is not a member mill, the manufacturer usually sets its own, or proprietary, grades. Some mills sell "mill run" flooring, which is not separated by grade at all.

In the United States, members of grading associations receive spot checks at the mill to ensure that the grade is consistent. The mills' own quality control managers are responsible for checking the quality of the grading.

As the flooring is separated, each grade is sent on a conveyor belt to be bundled. There are two types of bundles — random-length bundles consist of flooring that is all the same length, while nested bundles have flooring of varying lengths packaged together. The bundles are then strapped and loaded onto pallets. Pallets of random-length flooring are tallied for footage. At that point, the wood flooring is ready to be shipped to the distributor and the final consumer. .

Contributors to this article included Karl Anderson, Action Floor Systems; Marty Johnson, Cumberland Lumber & Manufacturing; Mike Knight, B.A. Mullican Lumber & Manufacturing; Bobby Millner, National Oak Flooring Manufacturers Association; and Keith Waldrop, McMinnville Manufacturing.