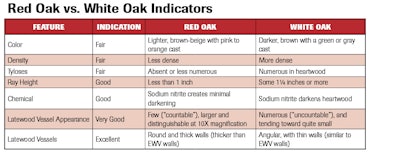

"What kind of wood is my floor?" When a homeowner wants to repair or add to a floor, this is what they ask. Spotting a floor that is "oak" is usually easy, but differentiating between red and white oak is not always straightforward. Most people in our industry have a vague idea that red oak tends to have a pinkish cast, while white oak usually has a greenish hue. Experienced installers can often tell the difference between the two by the overall look of the grain and color, although most wouldn't be able to fully explain exactly how they distinguish them. Experienced wood identifiers even use taste and smell to identify lumber species, but it's unlikely you'll be doing that on an older installed floor! Old finish or stain can make the identification even less certain unless you consider more detailed features.

The red oak and white oak groups are both made up of several species. Within each group, variation between the species can be noticeable. For example, Northern red oak, Quercus rubra, is denser and a deeper red than Southern red oak, Quercus falcata. Also, different growing conditions cause variation in density, grain and color. White oak grown in some locations can have a red-brown color that is more typical of red oak. Wood from older trees or slow-grown white oak can actually be less dense than fast-grown red oak, even though white is usually about 10 percent heavier.

These differences within the groups complicate the identification process. No one wants to install new wood only to find a mismatch when the finish is later removed from an old section of flooring. Fortunately, the grouping of red oak or white oak can be determined with a good degree of certainty before new wood is delivered. The confidence level is high when a small sample of the wood can be obtained for examination. The following are some steps you can take to be confident the next time you need a positive ID on a floor. From a scientific standpoint, Clue 3 is the only surefire way to make an identification, but let's proceed in an order in which you might see the features in an installed floor.

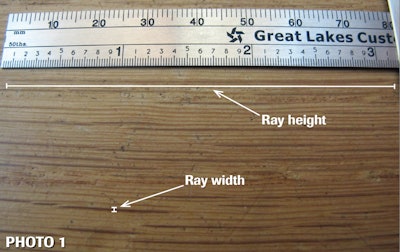

Clue 1: Ray Height

White oak flooring: Rays can be seen in this flatsawn white oak floor even though it is stained.

White oak flooring: Rays can be seen in this flatsawn white oak floor even though it is stained.

This method alone isn't failsafe: A wood science professor once handed me a piece of green rough-sawn wood and asked for the type of wood. It looked generally like white oak, but there were no rays even close to 1 inch tall. Judging by the ray height, I said red oak, but was wrong.

If the heartwood is present, another indication for white oak can come from chemical tests (sodium nitrite in a dilute solution). I hesitate to rely on this, or most single observations, as a sole determination of oak group. More extensive chemical laboratory tests are available if needed.

Clue 2: Examining Tyloses

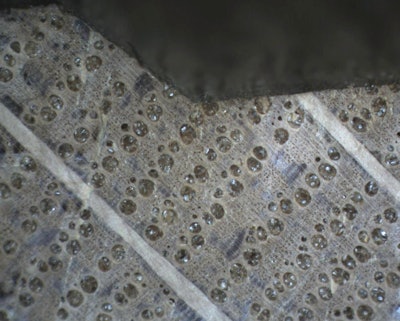

Red oak cross section: Having a cleanly cut portion of your specimen is helpful. Here, the details of the latewood vessels show more clearly in the cut portion (lower center) of this end grain. Hand lenses are in the background.

Red oak cross section: Having a cleanly cut portion of your specimen is helpful. Here, the details of the latewood vessels show more clearly in the cut portion (lower center) of this end grain. Hand lenses are in the background.

Good lighting helps, as the important features you need to see are quite small. Some of those important features are called tyloses. These are outgrowths that develop within the pores (vessels) during the transition from sapwood to heartwood that resemble miniature pieces of cellophane—some curved and some crumpled up. Finding numerous tyloses in the earlywood vessels (EWV) is an indication of white oak (see Photo 3). The EWV are the large pores that can cause stain bleedback problems.

Unfortunately, tyloses are also occasionally found in red oak, although they tend to be less numerous if they are present at all. An absence of tyloses in oak indicates either sapwood or red oak.

White oak cross section: One wide ray and many narrow rays are perpendicular to the rings. Tyloses are seen in earlywood vessels. Numerous latewood vessels and the darker fiber areas appear between the earlywood rings.

White oak cross section: One wide ray and many narrow rays are perpendicular to the rings. Tyloses are seen in earlywood vessels. Numerous latewood vessels and the darker fiber areas appear between the earlywood rings.

Viewing tyloses with an inexpensive 8X lens to tell which kind of oak it was kept me out of trouble with red or white for a number of years. The shape of the small pores, which will be discussed next, was also helpful.

Clue 3: Latewood Vessels

The most reliable separation of red oak and white oak wood comes by using the number, arrangement, size, shape and wall thickness of the small pores, which are called latewood vessels (LWV). These are the pores that form in the later part of the growth in a year.

Red oak sample: Fewer latewood vessels, which are nearly round, are found in red oak. The image includes one wide ray and many narrow rays. Parenchyma bands can be seen crossing the dark fiber regions.

Red oak sample: Fewer latewood vessels, which are nearly round, are found in red oak. The image includes one wide ray and many narrow rays. Parenchyma bands can be seen crossing the dark fiber regions.

Most of these properties can be seen with a hand lens with an 8X to 15X magnification. Red oak LWV are round, tend to be less numerous (characterized as countable using a hand lens), and solitary (not touching other vessels), occasionally occurring in single or double strings or groups (see Photo 4).

White oak LWV tend to be smaller and more numerous (uncountable with a hand lens), with a more angular outline. At first glance under low magnification, many white oak LWV might look round, but there tend to be a few where the angular nature is more pronounced. They are found in groups or bands that are characterized as flame-like. Again, looking at several red oak and several white oak boards makes it easier to recognize the appearance of the LWV in each kind.

Seeing the LWV cell wall thickness is easiest with higher magnification (Photos 5 and 6), although with practice and a hand lens with 10X–15X magnification, the thickness is visible. Techniques for higher magnification are described in R. Bruce Hoadley's book "Understanding Wood."

White oak sample: The latewood vessels have an angular outline and thin cell walls.

White oak sample: The latewood vessels have an angular outline and thin cell walls.

Clue 4: Other Properties of Oak

Oak is known for its wide rays, which are the primary features used to identify the North American red and white oaks. A prepared surface viewed with a hand lens shows light-colored cell types in addition to the rays (in two sizes, wide and narrow), and the vessels (in two sizes, large EWV and small LWV). These other light-colored cell types, parenchyma and tracheids, often surround the vessels. The LWV show as the small openings in these light areas. Lines of light-colored parenchyma are also seen running parallel to the growth rings (tangential direction) through the dark areas of fiber in the later part of the ring. In other words, if you have a ring-porous North American wood with rays of two sizes, the largest of which are more than 10 cells wide, and solitary vessels, it is oak.

Some Examples

Red oak sample: Latewood vessel details, such as being round and solitary, become more evident with higher magnification. Notice that the LWV cell walls are thicker than the white oak LWV cell walls.

Red oak sample: Latewood vessel details, such as being round and solitary, become more evident with higher magnification. Notice that the LWV cell walls are thicker than the white oak LWV cell walls.

Once you know what to look for, combining observations of several properties will increase the level of comfort with identification. For example:

• If your floor has rays over 1¼ inches tall, abundant tyloses and uncountable LWV in a flame-like pattern, it is very likely white oak.

• In a floor where you can't find any tall rays or tyloses, and the LWV are round and not too numerous, it should be red oak.

In either case, look at the LWV wall thickness and shape to be absolutely certain.

Pay close attention to the details, and remember to educate customers that oak is sold in groups of species. This might make an exact match to an existing floor difficult, even if you have identified the correct oak group.

Real-Life Example

|

Outside HelpIn addition to R. Bruce Hoadley's book "Understanding Wood," there are several online resources that can be used to help identify wood: Insidewood: insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu/welcome (use the search function) Maryland Oak ID: www.jefpat.org/wood&charcoalidentification/webpages-trees/theoaks.htm FFPRI: f030091.ffpri.affrc.go.jp/index-e.html Delta-key: delta-intkey.com/wood/en/index.htm PROTA: www.prota4u.info/searchresults.asp Also, wood identification services where you can send samples are available through governmental agencies, universities or consultants. Of these, the best known is the U.S. Forest Products Laboratory, which will identify up to five samples for free per year; samples may take up to four weeks to be identified. For more information, visit www.fpl.fs.fed.us/research/centers/woodanatomy/wood_idfactsheet.php. |

More from author Andrew St. James:

Understanding How to Measure Moisture Can Avert Job-Site Disasters

Understand the Science of Water and Wood Floors