When Cindy and Jim Carpenter asked Phoenix-based architect Bob Bacon to design the couple a "very European, very authentic" home, Bacon handed them a 113-question questionnaire. Of course, it was for good reason. Bacon needed to know every last detail, from what size furniture the couple wanted, to whether they exercise in their bedroom, to where they'd like wood floors installed. The Carpenters also provided Bacon with many photos of homes from their trips to Europe; most of them came from northern Italy. What resulted was Cindy Carpenter's dream house: an Old World, pan-Mediterranean dwelling, complete with reclaimed jarrah flooring, an indoor water feature and plenty of breathtaking views to boot. To Bacon it resembles a pre-industrialized home one might find packed between winding streets somewhere in a Mediterranean country.

"There are some values of Old World architecture that apply to all of the buildings of the old, pre-industrialized world, no matter where they were located," says Bacon, who in 2001 was named Design Master of the Southwest by Phoenix Home & Garden magazine. "Those buildings were built for permanence and durability. They were handcrafted."

Bacon emulated many Old World values to imbue the Carpenter's home with this character. As one approaches the home from the cul-de-sac, the first prominent structure is a bridge, reminiscent of a bridge over a medieval moat, Cindy says. She even asked her builder, Mark Malouf of Scottsdale-based Malouf Coble Custom Homes, to space the bridge's planks far enough apart so they would rattle as cars drove them. The home's exterior features stones integrated in the mortar, and some portions are covered in stucco. This emulates the fashion by which Old World homes were constructed in stages-home additions often took place within different economic or social climates, or as new technologies became available, which dictated the use of different building materials.

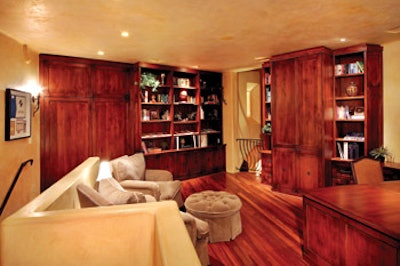

Elizabeth Rosensteel, owner of Phoenix-based Elizabeth A. Rosensteel Design Studio, incorporated Old World and pan-Mediterranean elements inside the home; she says she likes to take her cues from a project's architect when designing interiors. Faux-foundational stone was incorporated near the bottom of some walls, reminiscent of the time when earth-moving machines were unavailable. Venetian plaster, a finishing method that became popular during the Italian Renaissance, solidifies the home's Mediterranean appearance.

Striving to find a flooring product that would appear more hand-crafted and worn than engineered, Rosensteel chose reclaimed Australian jarrah. Malouf tapped Paul Newman, president of Phoenix-based Premiere Wood Floors and a 21-year veteran of the flooring industry, to install the 1,500 square feet of solid unfinished wood flooring. The ¾-inch thick, 3-inch-wide flooring came in random lengths up to 12 feet; in its previous life it served as flooring joists. Newman says the 12-foot-long pieces were difficult to work with at times-in general, he says, reclaimed jobs can be more difficult because the product is usually longer-but were worth the trouble because of the jarrah's unique variety and color.

"With reclaimed flooring, there is no duplicating," Newman says. "We can have [similar floors], but-depending on where exactly this wood came from, whether it was exposed or inside, how old it is, how it was cared for-every reclaimed job is unique."

To accommodate jarrah's exceptional density, Newman allowed the material to acclimate in the Carpenter's home for about one month. In Scottsdale, material typically should have a 6 to 7 percent moisture content, Newman says, and it is rarely near this level upon entering a job site. After installing and sanding the jarrah, Newman's crew finished the floor with a water-based finish. It took a crew of three workers about three weeks to complete the project.

As any wood flooring contractor knows, moisture is one of the biggest hurdles when installing a wood floor. This house had both extremes: Scottsdale's arid environment and a water feature adjacent to the floors. Carpenter knew she wanted a water feature in her house since day one. She remembered one in a house from when she was young. "I said to myself, 'Oh, my God, that would be my dream,'" she recalls.

Not only does the water feature fulfill one of Carpenter's dreams, but it also gives the home's driveway, walkway and foyer beautiful continuity. The water originates from scuppers in pools that wrap around the front of the home and converge next to the walkway to the front door. Fire bowls-another request of Carpenter's-sit between the scuppers, providing a primordial contrast of fire and water. Two times a day the scuppers erupt and send fresh water racing toward the front door. Just as people pass from the outside in, the water flows inside to narrow channels flanking the jarrah entryway. The jarrah has an overhang of two inches; it feels as if one is actually treading another bridge in the home's foyer as water flows alongside. Carpenter likens it to the sound produced by a small waterfall.

"We penetrated what is normally a very rigid boundary," Bacon says, "and we did that with the continuity of water. When you approach that front door there is water on both sides, and when you go through that front door there is water on both sides." As the water goes underneath the front door, it passes through a very fine filter, lessening any chance of bugs or snakes entering the home. To ensure the water is clear, it is treated much like pool water. For safety, the channels are narrow and only about a foot deep. For the wood floor's protection, a vapor barrier designed for basement walls lines the concrete pools so moisture cannot seep into the concrete and then into the floor. For additional protection, Newman added extra finish around the edges of the jarrah near the water.

This continuity between outside and in is always important in design and architecture, but one could argue it's even more important in Arizona because of its wide open spaces, deserts and mountains that provide breathtaking views and a great environment for entertaining outdoors. "Everything in Arizona is about the outdoor lifestyle, so the materials really have to flow inside and outside-that's just how we live out here," Rosensteel says. "We like to have spaces where all the doors open up. When you entertain, people are moving inside and outside, so you like to have that experience of the materials just continuing through, and that's how we approached the house."

With tactful precision, Bacon made the Carpenter's dreams come true, and "he got into our heads deeper than we realized he would need to be," Carpenter says. "There isn't a day that I drive up to my home and I don't-honest to God-say to my husband, 'This is the most magnificent home around.'"

Project Details

Architect: Bob Bacon, RJ Bacon Design (Phoenix)

Designer: Elizabeth Rosensteel, Elizabeth A. Rosensteel Design Studio (Phoenix)

General Contractor: Mark Malouf, Malouf Coble Custom Homes (Scottsdale, Ariz.)

Flooring Contractor: Paul Newman, Premiere Wood Floors (Phoenix)

Wood Flooring: Recycled Lumberworks (Ukiah, Calif.)

Finish Manufacturer: Bona US (Aurora, Colo.)