It's a resounding financial question from business owners: "What am I supposed to do with this balance sheet?" Because a balance sheet can be an essential tool in managing your business, it's imperative that you know not only what to do with the information from this tool but, most importantly, how to read it and understand what is on it.

Many business owners believe that a balance sheet reveals what their business is worth. Others believe a balance sheet indicates how much a bank will lend them. Both of these are only half-truths, if that. A balance sheet—in any business—is a statement that tells you what your business owns, what it owes and what is left over—and, it tells you this all at cost, not at fair market value.

Assessing Your Assets

The first section on your balance sheet lists assets. Assets are the things your business owns. On a balance sheet, assets are listed at cost, not at fair market value. The primary reason for this is that fair market value is subjective. You could list your assets at a higher fair market value than another business owner because you believe them to be more valuable, even though both company's assets are the same. This puts too much subjectivity into a balance sheet statement and can confuse an outside reader. Some people have suggested that appraisals be done, but having appraisals done every month would not be practical. So, assets—the items your business owns—are listed at cost.

To understand and better analyze your business, the assets are then broken into three categories—current,fixed and other. For analysis purposes,it is important to have assets listed in the correct categories.

Current Assets: This category should list cash and items that will become cash within the next 12 months, including any marketable securities your business owns, accounts receivable, inventories of all sorts and prepaid amounts. Because current assets are turned over so quickly, they usually are the closest to real value compared with other assets. They are, however, still listed at cost, even if the value changes before they are turned over.

• Accounts receivable are monies due your business for work performed. Your business owns the right to receive this money. Most businesses do not make sales expecting the monies to be received in more than 12 months. Therefore, accounts receivable will be turned into cash within the next 12 months.

• Inventories can be listed as raw materials, work-in-progress and finished goods. There also are allowances for obsolete inventory in some cases. Raw materials inventories are listed at the cost of the raw materials. Work-in-progress inventories include labor and other costs that go into producing the finished product along with the raw materials that are in process. Finished goods inventories are the items that are complete and waiting to be sold. Once they are sold, these items are no longer owned by your business and are moved to your income statement under cost of goods sold. Remember, inventories usually are purchased with the intent of selling them sometime within the next 12 months. Selling inventory turns it into cash.

• Prepaids are the last of the current assets. To illustrate, let's assume that your business has a 12-month general liability policy that is $12,000 per year. Let's say that the whole policy is due in January. You may pay for the whole amount, but you haven't used it all up in January. You have only used up one month's worth, or $1,000. You still own the right to receive $11,000 worth of insurance within the next 12 months. Because it is something you own and not something used up, you record it as a prepaid. When you look at your balance sheet and see a prepaid, you know your business owns the right to receive that amount of services/goods sometime within the next year. If your business were to close, those monies would be refunded to your business.

Fixed Assets: Fixed assets are things that you can touch, that last more than 12 months, and that are over a predetermined dollar amount. This predetermined dollar amount is used so that you don't waste time tracking small items. Most companies use an amount of $500 or more. All fixed assets get "used up" over several years and are no longer any good. This is known as depreciation.

Other Assets: The third category of assets is what is called "other assets." Other assets are things that you own and paid for, that will not be turned into cash within 12 months, and that cannot be touched. For most companies, the only thing in this section will be security deposits. Unless you leave the place of business, the security deposits will not be turned back into cash within 12 months, you own them and paid for them, and if you leave, they will be returned to you.

A balance sheet that is not comparable does not tell you much of anything, while one that is can tell you volumes

A balance sheet that is not comparable does not tell you much of anything, while one that is can tell you volumes

Knowing What You Owe

The next section on a balance sheet covers the things you owe, or liabilities. These are broken into two categories—current liabilities and long-term liabilities.

Current Liabilities: These are things that will use your company's cash within the next 12 months. Accounts payable and payroll taxes payable are examples of current liabilities. Another common current liability would be unearned revenues or customer deposits. Revenue is only recorded when it is earned. When a customer makes a deposit, this is not earned until the work is performed. When you see customer deposits or unearned revenue on a balance sheet, you know that your company owes someone goods or services in the amount listed on the balance sheet, and it is owed sometime within the next 12 months.

Long-Term Liabilities: These are simply amounts that will use your company's cash after the next 12 months.

The Equity Equation

The last section of a balance sheet deals with equity. This should not be confused with homeowner's equity; these are not the same thing. Equity on a balance sheet is simply what is left over after accounting for assets and liabilities. If you take the things you own, minus the things you owe, you have equity. A balance sheet also tells you who owns the equity. In most small businesses, this is the owner of the business. While this number does not equate to homeowner's equity, you could look at it as your ownership in the company.

In The Know

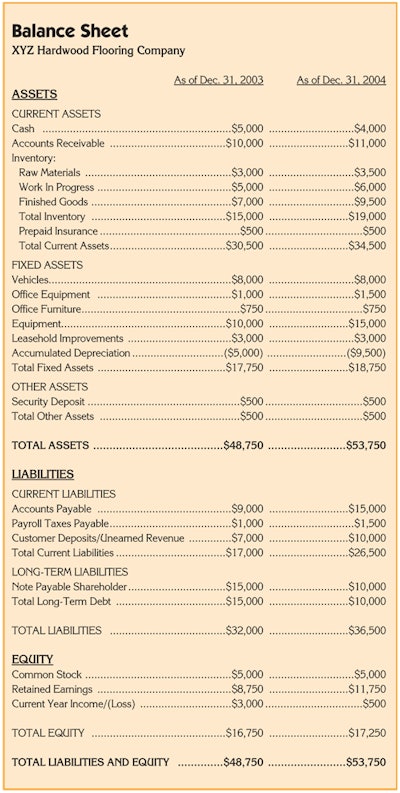

Now that we have discussed all the parts of a balance sheet, it's time to talk about what all that information can tell you as a business owner. First of all, in order to be of value, a balance sheet must be comparable. It must be presented comparing one period with another period like the example balance sheet pictured on page 50. A balance sheet that is not comparable does not tell you much of anything, while one that is can tell you volumes.

When analyzing a balance sheet, the first step is to make sure it balances. Assets must equal liabilities plus equity. Once it balances, compare the current assets minus the current liabilities from period to period. This number represents net working capital. The cash coming in within the next 12 months (current assets), less the cash going out within the next 12 months (current liabilities), represents the cash available to put into operations (net working capital). This number should grow as your business grows and stay stable when your business is in a maintenance mode of little or no growth. A decrease in working capital generally is a bad thing.

Next, it's time to look at inventory levels. Inventory turns should range from six times for a company with $500,000 in assets to 14 times for a company with $2 million-plus in assets. To calculate inventory turns, subtract the cost of goods sold from the profit and loss, and divide it by the average inventory. Average inventory is the beginning inventory plus the ending inventory, divided by two. If this number is much higher than expected, it could mean your business is not holding enough inventory to adequately meet sales. If the number is too low, it means your business is holding too much inventory for the amount of sales being made.

As your company grows, accounts receivable and customer deposits should be growing with the company. If your company is in a maintenance mode—not growing or declining—these numbers should be staying consistent from period to period. This same principle applies to the equity section of the balance sheet. In analysis, this is expected to grow as your company is growing and to be stable when your company is not growing.

If accounts receivable are growing and your company isn't, then your business is not keeping on top of its collections. If the accounts receivable are decreasing, it generally means a decrease in sales. If customer deposits are increasing and sales are not, then this means work is getting backed up. If customer deposits are decreasing, it could mean that sales are declining. When equity decreases, it either means that your company is losing money, distributing more to the owners than it is making, or a combination of both. When equity is growing, it is because your company is making money and not distributing all it makes to the owners. When equity is being maintained, it usually means your company is distributing what it earns to the owners.

As with every accounting question, the answer is always, "it depends." In analyzing a balance sheet, these are the general guidelines, but there are always instances when these guidelines need to be bent and re-examined because of what is going on in a business. In spite of this, using these general guidelines can put you one step closer to a better understanding and use of your company's balance sheet.