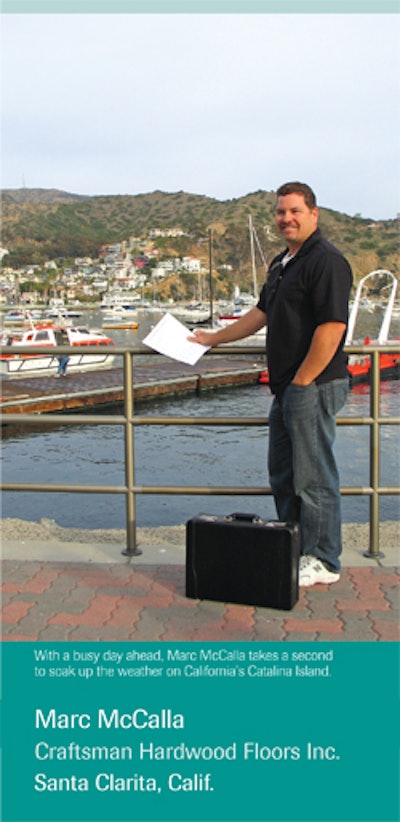

Ferrying to remote islands and cruising up the Pacific Coast both sound like leisure activities for the well-to-do, but for Marc McCalla, owner of Santa Clarita based Craftsman Hardwood Floors Inc., it's all part of the job. The 22-year hardwood flooring industry veteran started the industry on the bottom rung, but has elevated himself as a business owner and craftsman, and he now does custom installation and sand-and-finish work for some of the most exclusive clients in southwest California, all while keeping in mind his No. 1 priority—his family.

Hardwood Floors tagged along with McCalla on a more-than-300-mile journey one sunny day last May as he negotiated congested Los Angeles-area interstates and convoluted ferry schedules, and as he dealt with more typical obstacles that force a contractor to think on his toes.

5:30 a.m.

Most mornings McCalla wakes at 5:30 a.m. From his home office, he works on completing paperwork and scheduling, and making sure his boys get ready for school. Today, however, is a little different. Yesterday, he attended the National Wood Flooring Association's Wood Flooring Expo in Long Beach, Calif. Besides networking, visiting with friends and attending the expo, he stayed overnight in Long Beach to catch a morning ferry to Catalina Island, 30 miles off the Long Beach coast; there, he's doing an estimate for an esteemed client in Avalon, Calif.

6:15 a.m.

McCalla departs Long Beach from Catalina Landing aboard the Catalina Express, the sole passenger ferry between mainland California and Catalina Island. Today he's trying to complete his work so he can be back in Santa Clarita for a 6 p.m. lacrosse match in which his 17-year-old son, Garrett, is playing.

A round-trip ticket for the Catalina Express costs $66.50, and the 30-mile trip takes about one hour. Furthermore, construction supplies for any project on the island are delivered nightly while the tide is low. Mainland contractors must load the supplies on a barge and then pay someone on the island to receive and deliver the supplies. Because all vehicles on the island require a permit—for which there's a 20-year waiting list—mainland contractors cannot ship over a work truck, either, which makes them further reliant on island contractors for transportation and other logistics. Therefore, projects on Catalina Island generally cost twice as much as similar projects on California's mainland.

6:57 a.m.

McCalla catches a satellite TV traffic report on the ferry that shows a major jam on "the 405," or Interstate 405, the major north-south thoroughfare that bisects the Greater Los Angeles area, running from Irvine to San Fernando, Calif.; it's also one of the most heavily traveled roads in the United States. Luckily, the jam is heading south, but he knows that's no guarantee northbound traffic won't be jammed when he needs to migrate north later in the day. Los Angeles residents joke that the interstate was labeled "405" because its traffic often moves at about 4 or 5 miles per hour.

7:22 a.m.

McCalla arrives in Avalon and decides to grab breakfast at one of his favorite Catalina Island haunts, Sally's Waffle Shop. Most days, he eats breakfast at home, along with a cup of coffee. He's a little amazed by workers, especially contractors, who routinely forgo breakfast and rely on coffee throughout the day.

8:30 a.m.

After breakfast McCalla calls contractor Adrian Thoricht of Avalon-based Fine Line Construction. The two are working together on McCalla's first of four stops for the day, a condo that rests on a mountain slope northwest of Avalon. Adrian picks up McCalla with his Tiger Truck, a light utility vehicle that is popular on Catalina Island's winding roads. They begin a winding trek into the mountains.

8:49 a.m.

Catalina Island offers views typical for McCalla's clients.

Catalina Island offers views typical for McCalla's clients.

They pass the community guardhouse and make a few hairpin turns before arriving at the door of the condo, just one unit in a stack of several gleaming, symmetrical condo rows that veil a small Catalina mountainside.

Working in similar locales is not new to McCalla; he services a higher-end clientele regularly. He points to the work he did after attending his first NWFA school in 1996 as the work that took his business "to the next level." By 2002 he had won his first Floor of the Year award. When he began working on wood floors in 1987, it was "by trial and error," he says, and once wood flooring inspector Steve Marley was called in to inspect one of McCalla's jobs. McCalla remembers this meeting fondly, and says Steve told him, "I'm not here to criticize you—I'm here to offer advice." Marley then suggested McCalla and his crew attend some schools, and the rest is history.

Normally, McCalla would not have taken a job that requires between two and three travel hours each way. He considers his primary business area to be Ventura County and the Santa Clarita Valley, areas north and northwest of Los Angeles, but he has a 20-year relationship with this client. He highly values personal client relations like this one and makes a real effort to do as much business as possible in-person, as opposed to relying on phones and e-mail. Once work begins at the condo, he and his crew will most likely stay overnight on the island; however, he usually works just four days a week in these overnight situations so he can spend three days with his family.

McCalla is gathering measurements for a complete remodel of the condo, which will involve removing existing wood flooring and carpeting to lay 800 square feet of hand-distressed engineered flooring. While inspecting the site he discovers something that causes him to reevaluate his plan: Underneath the existing floor is a lightweight concrete subfloor, which could become damaged while removing the old floor. He's now deliberating between recommending a simple sand and finish or installing a new floor on top of the existing floor. The latter choice brings with it the headache of dealing with changing elevation throughout the condo, but the former choice won't give the client a brand-new floor like she requested. He'll have to confer with the client once more before making this decision.

10:30 a.m.

McCalla leaves Catalina Island but does not depart for Long Beach as planned. Originally, he thought the return ferry to Long Beach was leaving now, but this ferry's actually headed for San Pedro, a neighborhood 15 minutes west of Long Beach; the return ferry to Long Beach does not leave until 11:45, so he'll have to catch a cab from San Pedro to Long Beach. It's a small wrinkle on the day, but it doesn't surprise him. "Each day is different, and every job has new challenges," he says. "It's good because those are the jobs you learn on, but sometimes you ask yourself, 'Why can't this just be easy?'" He's learned from experience that the Catalina ferry's schedule can be unforgiving; ferries depart promptly, not waiting for passengers sprinting to the gate, and departures can be canceled without notice, which can steal an entire day.

11:41 a.m.

McCalla boards the Catalina Express to San Pedro.

McCalla boards the Catalina Express to San Pedro.

After arriving on the shores of San Pedro, McCalla hails a cab to Long Beach—the final tally: 15 minutes and $26. In the Catalina Express' parking lot he hops into his '92 Econoline van to begin the hour-and-a-half trip to his shop in Saugus, Calif., a Santa Clarita neighborhood. Along the way he calls to check in with his workers on their daily progress.

McCalla says it would be nice to outfit his company with new vehicles—the van he's driving and another have logged more than 300,000 miles each—but he's content to own a practically debt-free company; he owns three vans, one truck, one enclosed trailer, and tools for two sand-and-finish crews and one installation crew. He's proud to say the only business item on which he still owes money is a 2007 Chevy Suburban. This fact is critical in today's economic situation. "If I don't work for a week, I'm not going to drown," he says.

1:40 p.m.

The ferry mix-up leaving Catalina Island has put McCalla slightly behind schedule, lessening the chances of his enjoying his son's lacrosse match later. He had planned on stopping at a sit-down restaurant along with his guest journalist for the day, but settles on fast food at El Pollo Loco. His wife, Nicky, usually packs him a lunch four days a week in an effort to help him avoid restaurants (especially fast food) every day.

With lunch to-go in hand, he steers the van toward Montecito, Calif., a 73-mile drive west that will take him through mountains to the Pacific Coast. He makes a phone call at the beginning of the trip, but he can't hear it too well. Then, he discovers the battery of his hands-free device has died—he'll have to spend the rest of the day in violation of California Vehicle Code 23123, which states that drivers must conduct cell phone conversations with a hands-free device. Cell phone in hand, he calls Installation Foreman Joel Yahuetenez to discuss a time card Yahuetenez must submit to McCalla's contracted payroll company.

2:55 p.m.

Today, Yahuetenez and his crew have been working on the full renovation of a French country ranch in Montecito, one of the wealthiest areas in the United States, and home to magnates like Oprah and Steven Spielberg. At 10,000 square feet—3,000 of tear-out and new installation, and 7,000 more of sand and finish work—this is a big job for them. McCalla first passes a security gate and then ascends the nearly mile-long driveway flanked by heavy vegetation. At the top of the driveway crew vehicles from at least five contracting companies litter the home's turnaround and front lawn. The view at the top is impressive: Down below, the rest of Santa Barbara County—a plush, green landscape through which the occasional roof pops like a prairie dog; and the view to the south: the Pacific Ocean. He enters the front door, the beginning of a maze of power cords, dangling wires, blue tape and enveloping plastic sheets. The air is heavy with sawdust, and it's loud, too; nail guns and hammers strike unpredictably and often, while vacuums, air pumps, and fans draw dust outside. Entire walls have either been removed or bear the scars of electrical system renovation.

Earlier in the day, McCalla's crew was tearing out the main office and master bedroom floors. Now, they're cutting a slew of Dutchmen after the GC told McCalla he wanted the shoe removed from the baseboard throughout the home. (As work continued on this project three days later, McCalla and his crew were choking on a thin veil of smoke from a California wildfire raging just miles from the home.) McCalla tells his crew they can go home a little early this Friday before speaking with the general contractor about the installation schedule. The GC would rather McCalla not rack the floor to let it acclimate, but McCalla counters, "Floors don't acclimate in bundles." During this conversation McCalla notices a 4-inch chunk of granite that has broken off a balcony threshold in the bedroom, and he points it out to the GC. "How are you going to fix that?" the GC asks. McCalla laughs, however, he doesn't immediately assume his workers did it; he trusts them to be forthcoming in these situations, and they haven't yet said anything about it. At a replacement cost of $4,000 to $5,000, it's important McCalla gets to the bottom of the mystery.

3:28 p.m.

McCalla must now make his way to Hope Ranch, Calif., a neighborhood just 10 miles west of Montecito. Along the way he calls his sanding foreman Miguel Martinez to discuss the broken threshold. Martinez says his workers didn't say anything about it, which leads McCalla to believe his guys are in the clear. He calls the GC and leaves a message.

4:04 p.m.

McCalla's Econoline braves California's notorious highways.

McCalla's Econoline braves California's notorious highways.

About 10 hours into his day, McCalla arrives in Hope Ranch. His first of two stops in this area is a large, secluded estate. He meets a personal secretary and is escorted inside the home past two pet goats. McCalla was awarded this job nearly 18 months ago, and the clients have decided to move the project forward. He'll be sanding and refinishing the kitchen's pine floor, which has been worn to bare wood in spots. The secretary informs McCalla he'll also be tearing out and reinstalling a floor in the butler's kitchen so it matches the main kitchen. He takes some measurements and discusses sample delivery and furniture removal—thankfully, the clients have their own furniture moving labor. He is certain to remind the secretary that table chair dents will most likely reappear after the pine re-sand. McCalla plans on beginning the work at the start of the clients' three-week vacation.

McCalla leaves the primary residence and heads to a different location on the property where he'll be installing floors in a renovated garage that will house commercial offices. Upon entering the site, he's greeted with hugs and hellos from the designers, with whom he's worked in the past. "I feel good when something like that happens," he says. "Those are the feelings I want to reciprocate to my colleagues, and it makes me want to accommodate them as much as possible." The designers exit and then McCalla does a walkthrough with the GC. McCalla will be installing about 2,500 square feet of French oak, and the two discuss the various carpet and tile transitions he'll have to make.

McCalla gathers final measurements. One new detail that arises is moisture. The GC tells McCalla there is no vapor protection enveloping the concrete slab, and McCalla grows more concerned when he's informed the water table was found a mere 27 feet below ground when drilling wells for the structure's geothermal heating unit. He'll have to do a calcium chloride test, and depending on the results, he may have to spend more on subfloor prep materials. McCalla says he'll complete the test in the coming week, after which he should be able to begin installation.

5 p.m.

The fact that these last two stops of the day are more than 70 miles from his shop doesn't deter McCalla. "I don't mind the drive. [The work] is really high-end, and I love the challenge," he says. However, he's now a half-hour from Saugus, and he will not be able to watch Garrett's lacrosse match.

6:34 p.m.

McCalla arrives at his shop in Saugus and begins the short trek to his home for a family dinner—his son actually decided to forgo his lacrosse game in order to spend time with extended family who just arrived in town. "I'll never regret time with my family, but I might regret time I'm away from them," McCalla says.