By all standards, Gustave Caillebotte led a very full but short life. Born in 1848, by his early twenties he was already a lawyer and an engineer and had fought in the Franco-Prussian War. By his late twenties, he and his brother inherited a vast fortune from their father who sold uniforms, blankets and other textile products to Napoleon’s army. Since he no longer needed to focus on working for a livelihood, he turned his attention to his interest in art. His timing coincided with an emerging art movement known as Impressionism, and he quickly befriended many of the giants, as they saw strong potential in his artwork.

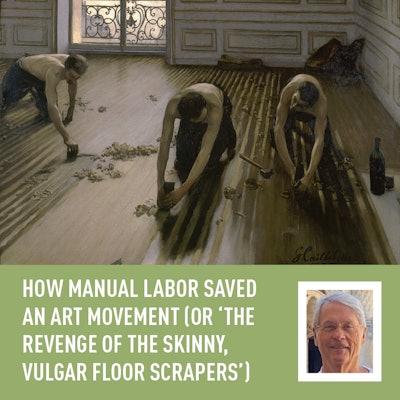

Along with his fellow artist, Caillebotte submitted eight pieces of his work to the Salon de Paris in 1875, an art show of the Academie des Beaux-Arts, the governing body of art in France. Among the eight pieces he submitted was “The Floor Scrapers.” The painting is large—3½ feet tall by 5 feet wide—and depicts three men in the process of scraping/refinishing a wood floor:

Historians have determined the room was Caillebotte’s own studio at 77 rue de Miromesnil in Paris. The painting defined the intent of impressionist art, which was to give us a peek at a moment of time in ordinary life. Much like the emerging interest in photography, Impressionism captured people simply going about their daily life: picnicking, having lunch in a bistro, rowing a boat on a quiet river, reading, walking in the rain with an umbrella or working on a wood floor. Prior to this time, popular art looked staged, organized, theatrical and formal. The brush strokes created clear objects, not the slightly blurred subject in impressionist paintings.

The critics and judges were not happy with what they saw, and they were brutal with their comments. “The Floor Scrapers” was singled out and deemed “vulgar and crude,” as it violated the unwritten law of popular art by showing the urban working class just going about their business. One critic took it further and ridiculed the workers, saying, “the arms of the planers are too thin and their chests too narrow.” The sight of bare-chested men engaged in manual labor was so offensive, Caillebotte was asked to remove the painting from the show. A year later he made another attempt at a similar scene, but it is tepid by comparison:

He put a shirt on one worker and changed the direction of their work. In the original version the workers’ momentum was directed right at you. It was bold, had force and you could easily imagine the noise of their work. It was dynamic, whereas the second attempt deserved no better than a yawn.

The rejection and ridicule from the critics had a chilling effect on Caillebotte. He continued to paint but he didn’t put any of his work up for sale. Because of his wealth, that wasn’t a problem for him, but for his cadre of artist friends, the negative comments and criticism were problematic. The critics threw a wet blanket on this art form, and the lack of public interest stifled sales. The movement needed help, and Gustave stepped up to the plate and delivered—big time.

Using his fortune, Caillebotte started buying and amassing the largest collection of Impressionist art of that era. He started filling his house and warehouse with works by his colleagues: Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro and a host of others. This provided an income stream for his friends and kept them out of poverty. Because of his real estate holdings, he provided them with free studio space and helped make sure they were well-stocked with materials and supplies to continue painting. This helped them weather the effects the critics’ comments had on the sale of their artwork and buy much needed time.

RELATED: Italian Wood Flooring Pros Recreate Famous French Painting

Caillebotte's father had died at an early age, and he suspected he would suffer the same fate—and he was right. He died in 1894 at the age of 45. In his will he stipulated that his large collection of Impressionist art, along with his own paintings, should be given to the country of France and be displayed in large, well-known museums. By putting the paintings in public museums, the masses were getting to see this art form for the first time, and suffice it to say, they liked what they saw. The net effect of this rise in popularity was an increase in demand for these paintings. Though Caillebotte died early, most of his colleagues outlived him by decades, and this increased interest allowed them to capitalize on their newfound fame and sell more of their artwork.

Those of us in the wood flooring industry have always seen “The Floor Scrapers” as a beautiful tribute to our noble trade—something of a cross-generational tribute to those who saw no shame in manual labor and considered it a key component to an honest way of life. What we didn’t know was that its callous dismissal when it was first viewed set in motion a sequence of events that would change the world of art forever. The Impressionist movement challenged the old academic norms of art and gave the public and the masses more of what they wanted to see: normal people involved in normal life. Today’s art historians readily acknowledge Caillebotte’s generosity and philanthropy played a major role in Impressionism’s success. There is sweet poetic justice that “The Floor Scrapers” not only survived but has become one of the most famous and recognized Impressionist paintings in history. Good on you, Gus, you deserved this.