Many maple flooring companies began as offshoots of sawmill businesses. Such was the case with the Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Co., where these scenes were captured early in the century. The Yawkey-Bissell mill in White Lake, Wis. (above) became the site of a present-day Robbins plant.

Many maple flooring companies began as offshoots of sawmill businesses. Such was the case with the Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Co., where these scenes were captured early in the century. The Yawkey-Bissell mill in White Lake, Wis. (above) became the site of a present-day Robbins plant.

At one time, maple hardwood floors were an essential part of everyday American life. They covered the floors of huge factories, schools and post offices, among myriad other uses. Business was booming, the forests seemed endless, and the leading manufacturers saw the need to create the Maple Flooring Manufacturers Association, introducing a system of standards and grading to the growing industry.

That was 100 years ago, and as the association recognizes the centennial, it celebrates with its five remaining member manufacturers. Those companies function in a market greatly changed from the heydays of early in the century, but they have deep roots and family ties in the industry.

While the MFMA's member manufacturers were once scattered throughout the Midwest and areas of the Northeast, today's members point out that their mills are practically within throwing distance of each other in northern Wisconsin and Michigan's Upper Peninsula. The story of how the five member companies made it to this point is a labyrinth of business and familial relations that goes back more than 100 years.

The present-day industry began when William "Sam" Horner ran out of pine resources for his planing mill in Reed City, Mich., in 1891 and converted the existing mill to the manufacture of hardwood flooring — becoming, the company claims, the first mass-producer of hardwood flooring. Until that time, hardwood floors were a luxury created by hand.

By 1897, the industry saw the need to create the MFMA. With the creation of the association, a common system of grading and dimensions was adopted by all members.

Another of the MFMA's oldest members was created in this era, as well. Connor Forest Industries, a forerunner of today's Connor/AGA, was started by two brothers in 1872. The Connor brothers logged and milled their own forests in Wisconsin and Michigan, and then moved into the maple hardwood flooring business.

Meanwhile, disappearing forests in Michigan's Lower Peninsula caused Horner to move to Newberry in the Upper Peninsula. When Horner's partner, Albert Abendroth, left the business, he went to Rhinelander, Wis., and joined Chauncey "Cockey" Robbins, forming the present-day company and MFMA member Robbins in 1919.

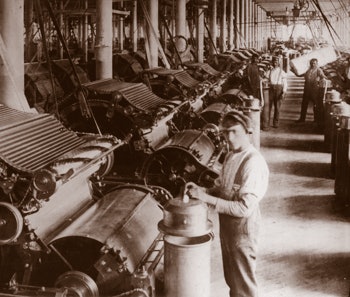

Cotton mills in the southeastern United States were among the many industries that required great expanses of maple hardwood floors around the turn of the century.

Cotton mills in the southeastern United States were among the many industries that required great expanses of maple hardwood floors around the turn of the century.

During those early years, the bulk of the maple flooring manufacturers' business differed greatly from the sports flooring market most associate maple flooring with today. At that time, big flooring business meant commercial building. "Because transportation wasn't what it is in this century, people tended to build multistory buildings for manufacturing or offices in metropolitan areas," explains Jim Stoehr, CEO of Robbins. Because railroads were the main mode of transportation, he explains, industry had to be located at main rail sites. The resulting huge buildings were wood frame construction with maple floors. "Because of its hardness and tightness in the grain, it wore quite well," Stoehr says.

As the industry entered the years of the Depression, Horner made a final move to its present location in Dollar Bay, Mich., in 1931, and Robbins opened a second location at Horner's previous plant in Newberry. As they did in the rest of the country, those years presented a struggle for the industry.

"Things just came to a screeching halt," says Bill Gamble, an AGA founder who grew up in those years at his family's Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Co. mill and flooring plant in White Lake, Wis. "The mill never shut down, but they stacked up a lot of lumber — 40 million feet," he remembers. Tensions ran high in company towns such as White Lake, where employees were paid in script with coupons for the company store instead of with money.

Turn-of-the-Century Textile Factory

Turn-of-the-Century Textile Factory

As the economy recovered, the industry also recovered its primary business of industrial building, but it began a great period of transition as it moved into the years of World War II.

"The wartime changes were very important to the whole flooring industry in that they had to make major adjustments," says Carl Abendroth, another AGA founder whose family involvement dates back to the beginnings of the industry. "They were forced to take a long look at costs and methods of production because labor was difficult to get." During the war, Carl Abendroth's father, Walter (son of Albert), who was then president of Robbins, worked with the government's Office of Price Administration to help set prices for maple flooring.

It was during that time that several key changes in the plants were in progress. Albert Abendroth had invented the machine that put a tongue and groove and a face on the boards in one step instead of two, greatly increasing efficiency — an innovation for which he was honored by the MFMA in 1946.

Meanwhile, the quality of the industry's floors also improved due to improved drying systems. Until then, "kiln drying in those days was not done properly," says Gamble. "There weren't any charts, gauges ... nothing that regulated the steam or heat or anything else that went into properly drying wood," he recalls. "The old dry-kiln operators would go in there and sniff it and if it smelled right to them, they pulled it." He remembers how even the schoolhouse floor in White Lake squeaked and had cracks due to poor drying. "If it isn't done right in the dry kilns and in the yard there's no way you can make a good product — but back in the late '30s and early '40s, we didn't know that," he says.

As WWII hit, the industrial maple floor industry was booming — here at the Red Dot Potato Chip plant in Madison, Wis., in 1939.

As WWII hit, the industrial maple floor industry was booming — here at the Red Dot Potato Chip plant in Madison, Wis., in 1939.

With the advent of improved kiln monitoring, floors improved, but the bulk of the maple flooring work was disappearing. As semi trucks and cars became the preferred method of transport after the war, businesses moved out to the suburbs, marking the beginning of the end for the huge multistory factories that had spurred the industry's growth for so long.

Sounding the final death knell for that segment of the industry was the debut of new floor coverings. "Linoleum and carpet got in the picture, and as a result these companies couldn't make it any longer," says John Hamar, former Horner president. As the industry faced hard times, many of the old-timers chose to simply retire and pack up their businesses. Others, such as the Gambles' Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Corp., chose to diversify from maple and hit the residential oak market.

Jim Stoehr remembers that the last two maple factory jobs his family's Cincinnati Flooring Co. did were in the late '50s, when the construction companies would lay 2-by-6's vertically over steel construction and nail the floors on top of that. "We did have a factory job in the early '60s that was going to be a 200,000-square-foot maple Robbins floor — at the last minute, they cancelled it and went to vinyl," Stoehr recalls. "Wood was more expensive, and it lost its appeal to the commercial and industrial market."

What was evolving during those struggling years, however, was a burgeoning market for school gymnasium installations. The actual floors had become more advanced during the years encompassing World War II, recalls Carl Abendroth. "After the war, the concept developed of manufacturers offering floor systems. Instead of just running hardwood flooring as a product and selling it through wholesalers, they started developing dealers who were contractors."

RELATED: The History of the Wood Flooring Industry

Systems such as Robbins' Ironbound Continuous Strip, a mastic set system developed by Carl's father, Walter, were only beginning when WWII arrived. "That method of setting up specifications worked well with the government, which was looking for that kind of information," says Carl, who himself was sent to Washington during the Korean War to work with the Office of Price Stabilization to set price ceilings in the industry. During the '50s, more advanced, cushioned systems with rubber pads began to appear.

"Construction had been virtually curtailed during WWII, and afterwards, you saw a tremendous need for new school buildings in the '50s and '60s," says Jim Stoehr. "It was an incredible number of schools being built." His family's Cincinnati Floor Co. would install as many as 100 gymnasiums in a year.

Assembled maple blocks from Robbins form the tennis and basketball courts at the Naval Militia in New Rochelle, N.Y., circa 1934.

Assembled maple blocks from Robbins form the tennis and basketball courts at the Naval Militia in New Rochelle, N.Y., circa 1934.

But the school-building frenzy couldn't support all the manufacturers, and by 1960, only 11 manufacturing companies remained on MFMA's membership. Most went out of business during the following decade. It was during this period that Robbins' Walter Abendroth and his brother Paul bought partnership in the Gambles' Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Corp. and moved Robbins' headquarters from Reed City to the Gambles' White Lake plant. Yawkey-Bissell then took the better-known and better-marketed Robbins name. Shortly after, in 1962, the Abendroth family sold Robbins' operations, but not the company, to E.L. Bruce Company (now Bruce Hardwood Flooring), with Carl Abendroth staying with the company as president and Robbins retaining its name.

Likewise, in 1960, another one of the industry's oldest names underwent a major change, as Horner was sold to the Hamar family, which had been involved in the sawmill segment of the industry. A new company to the industry came on the scene at that point — Harris Manufacturing, already a hardwood manufacturer, began to offer Bondwood, a maple parquet floor for basketball surfaces.

As the boom in school gymnasium construction began to wane, the industry was faced with another challenge. "In the mid '60s, it looked like there would be a real problem when synthetics came on the market," says Carl Abendroth. "It became the thing to have a synthetic floor in a gymnasium, but by 1970, it became obvious that there were major problems, and negative feelings about maple flooring started to go away." As the mid '70s hit, maple was again a growth industry, although synthetics remained an omnipresent threat.

First-grade maple strip painstakingly goes into this '30s San Francisco recreation center.

First-grade maple strip painstakingly goes into this '30s San Francisco recreation center.

By this time, the use of portable sports floors was becoming commonplace. "Years ago, it was more common to have separate facilities for basketball and hockey — construction costs were lower than what they are today," says Doug Hamar, president of Horner. "Nowadays, you could have a basketball game one night, a circus the next and hockey the next." That trend took a firm hold in the '70s.

The changes among the manufacturers accelerated throughout the decade. Horner bought the inventory and customer list of Ahonen Lumber Co., another industry stalwart. And in 1975, Carl Abendroth left Robbins, taking the White Lake plant manager, Bill Gamble, with him. They joined Roy Ahonen at a small plant he had picked up in Amasa, Mich., and started a maple flooring company — AGA.

"The three of us decided we would take this rundown, dilapidated plant ... the only thing we had were some dry kilns," recalls Bill Gamble. "We had been in the flooring business our whole lives and thought it would be fun — it was work!"

While the three of them turned the Amasa plant around, Robbins underwent another major change — Cooke Industries, which had acquired E.L. Bruce Company and Robbins, sold Bruce to Triangle Pacific, which was involved in the kitchen cabinet business and looking for a complementing hardwood floor business. When Robbins' sports floor business didn't fit the scheme, the Stoehr family moved in. "We were one of their major customers [at Cincinnati Floor Company] and decided to put together a package and buy it," he says, and Robbins remains with the Stoehr family today.

In 1957, MFMA members meet to celebrate the association's 60th anniversary. From left to right: J.B. Albee, MFMA field engineer; Roy Ahonen, Ahonen Lumber Company; G.K. Nixon, Oval Wood Dish Company; P. Fred Taylor, Connor Lumber Co.; Lloyd M. Clady, MFMA secretary/manager; Donald DeWitt, Holt Hardwood Company; William W. Gamble, Yawkey-Bissell Hardwood Flooring; W.C. Abendroth, Robbins Hardwood Flooring; Sam A. Wells, J.W. Wells Lumber Company; Peter S. Gamble, Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Company; C.A. Brand, North Branch Flooring Company; J.C. Christie, Robbins Flooring Company; Carl W. Abendroth, Robbins Flooring Company. In foreground from front: B.R. Millington, North Branch Flooring Company; Edward J. Stone, Horner Flooring Company; Hugh Reading, representative from Kramer Kraslet (advertising firm).

In 1957, MFMA members meet to celebrate the association's 60th anniversary. From left to right: J.B. Albee, MFMA field engineer; Roy Ahonen, Ahonen Lumber Company; G.K. Nixon, Oval Wood Dish Company; P. Fred Taylor, Connor Lumber Co.; Lloyd M. Clady, MFMA secretary/manager; Donald DeWitt, Holt Hardwood Company; William W. Gamble, Yawkey-Bissell Hardwood Flooring; W.C. Abendroth, Robbins Hardwood Flooring; Sam A. Wells, J.W. Wells Lumber Company; Peter S. Gamble, Yawkey-Bissell Flooring Company; C.A. Brand, North Branch Flooring Company; J.C. Christie, Robbins Flooring Company; Carl W. Abendroth, Robbins Flooring Company. In foreground from front: B.R. Millington, North Branch Flooring Company; Edward J. Stone, Horner Flooring Company; Hugh Reading, representative from Kramer Kraslet (advertising firm).

As the industry entered the '80s, Bill Gamble had left AGA and returned to work for Robbins at White Lake. In 1986, AGA was sold to BRC, a Swiss company that had bought Connor Forest Industries and its Connor Flooring Division in 1982. BRC ran the two companies as commonly-owned competitors until 1991, when the companies were merged into the present-day Connor/AGA.

The sale of AGA led to the start of the two youngest MFMA-member flooring companies. When BRC bought AGA, it closed its Connor plant and management in Wausau and Laona, Wis., leaving those employees looking for work. Floyd Shelton, who had worked for Connor and previously for Cincinnati Floor Company, gathered resources and started Superior Floor Company in 1986 with unemployed Connor employees.

Three years later, in 1989, Action Floor Systems started, continuing the fifth generation of the Abendroth family's involvement in the business. Carl's son, Tom, his son-in-law, Gary Stephenson, and Herman Krahn had learned the maple flooring business working for AGA. They joined with Dan Corullo, who was in the sawmill business, and started production of Action maple floors in Mercer, Wis.

As the two newcomers got their feet on the ground, Horner was sold to an investment group called The Ventures Group in 1988, although it was sold back to the Hamar family, who had remained involved in the company, in 1993. Meanwhile, Connor/AGA was sold in 1992 by BRC to Balsam Company, a German company with vast involvement in sports surfaces, including Astroturf. When Balsam declared bankruptcy in 1994, Connor/AGA was sold to its current owners, The Harvard Group — marking the last of recent major company changes among the present MFMA members.

But that's not to say that the market and product aren't changing. While the wood itself remains constant — "They still make flooring the same way they made it in 1891," says John Hamar — the entire concept about sports floor systems has evolved.

"The focus had been more on stability and putting in floors that would last the life of a gym that wouldn't buckle or warp," says Jim Stoehr. While that was a laudable goal, it didn't take the athletes into account, he says. He tells how, for instance, in the '80s Robbins installed a floor at the new facility for the University of Cincinnati basketball team. "We put in a low-profile, anchored system that wouldn't buckle, but it's hard as a rock," Stoehr says. As of last fall, a new portable system rests on top of it.

That's a focus and source of competition throughout the industry, says Action's president, Gary Stephenson. "The various companies have their own systems that allow the floor to absorb most of the impact from a falling or jumping athlete, while also ensuring that the impact doesn't move the floor so that it adversely impacts another player," he says.

As they develop their compliant and resilient sports floors, some manufacturers also are enjoying a newfound popularity of maple in residential use.

"It's amazing how that's changed," says Carl Abendroth. "I can remember when we set up marketing programs back in the '50s and '60s, we didn't pay any attention to the residential market — it wasn't worth spending time and money on." With the trend in interior design to the light look, maple has naturally gained market share. Harris-Tarkett (Harris Manufacturing's name changed after being purchased by Tarkett in 1983), an MFMA member until 1996, now focuses most of its maple energy on prefinished and laminated floors for the residential market and some industrial applications.

While the manufacturers acknowledge that residential market, the bread and butter for most MFMA members remains the sports floors, and that's where the MFMA has focused its efforts in recent years — a main goal being to battle off the synthetic surfaces threat.

Since then, a 1988 study commissioned about injuries on sports floors showed a 70 percent greater chance of athlete injury on a urethane or PVC floor compared to an MFMA floor. Continuing a stronger advocacy role, the association also commissioned a study by an independent research firm comparing life-cycle costs of MFMA maple flooring with synthetics — the results showing that costs of either urethane or PVC were more than 40 percent higher. "Synthetics have become far more sophisticated," says Neal Hamlin, marketing consultant for the MFMA. "What the MFMA is trying to do is counterbalance."

That has helped make maple flooring's story in recent years a prosperous one — by 1994, MFMA maple had risen from 48 percent of the U.S. sports floor market in 1984 to 54 percent, and observers predict more growth for the residential maple market. For now, at least, the future for the five manufacturers and the association looks pretty stable — and it's about time.