For centuries, wood floors were the domain of only the wealthiest people in the world. Expert craftsmen labored for years on the same floor, meticulously cutting each intricate inlay or pattern by hand. The only other wood floors in existence were the rough, hand-hewn planks that formed the surface of some commoners' residences. Either way, each wood floor was the result of a painstaking hand-cutting process.

The wood flooring industry more closely resembling the one we know today began just before the turn of the 20th century. In 1885, the side-matcher was developed, creating flooring with a groove on one long side and a tongue on the other. This new milling allowed wood floors to be blind-nailed. The flooring was 7/8 inch thick, 2 1/2 or 3 1/4 inches wide, and most pieces were at least 8 feet long. Thirteen years later, in 1898, the end matcher appeared. Until that point, all flooring ends of each piece had to be on joists, as subfloors were not commonly used. The mechanized manufacture of wood flooring prompted the suppliers to organize associations for the industry — the Maple Flooring Manufacturers Association began in 1897, and the Oak Flooring Manufacturers of the United States, precursor to the National Oak Flooring Manufacturers Association, traces its beginnings to 1909.

As the 20th century began, several important changes occurred in the industry. The side-matcher could allow hollow-backing on the boards, making them lighter and allowing them to conform better to subfloors, which were beginning to be commonplace. Flooring dimensions slimmed down: 5/16-inch, square-edge flooring and 3/8- and 1/2-inch flooring were introduced, helping to decrease hefty freight charges. Central heating was coming on the scene and wreaking havoc with the wood floors, but the advent of the dry kiln gave flooring a better chance to succeed in normal living conditions.

The flooring mills burned their waste to generate their own electricity and heat. One such mill was North Branch Flooring Co., which was incorporated in 1906 in Chicago and still exists today as an eighth-generation family business, now as a distributorship. For their northern red oak and maple, the company got lumber by boat, explains President Bob Edwards: "We used to get shipments of wood through the Great Lakes, then up the Chicago River on a schooner. We'd unload it right onto our docks here."

Manpower

While the flooring mills were generating their own power, the installers in the field had nothing but their own physical strength and a few tools to get the job done. "When my father started the company, he used to go to work by streetcar instead of having a truck," says Fred Galliford of the 80-year-old contracting business Sid Galliford & Sons in Weston, Ont. "He'd carry a box of tools when he went to work — he didn't have a sanding machine."

RELATED: A History: 100 Years of Maple Wood Flooring

Starting a business at the beginning of the Roaring '20s was good timing for the floor man. "People had a lot of money in the '20s; there was a lot of cash around," Galliford explains. "He did borders and basketweaves and things like that, all hand-cut and hand-laid. It was labor-intensive work. Those guys were real tradesmen."

Perhaps the most labor-intensive aspect of the job was the scraping process. Instead of sanding the floor, men would go down on their knees and pull scraper blades across the floor. "When I was a kid and I would complain to my dad about running the edger, he would say to me, 'What are you complaining about — at least you've got a machine to do it with! You'll be done in an hour rather than taking all day to do it!'" recalls Bill Price Sr.

Contractor Sid Galliford bought his first work truck in 1923 — a Ford Model T. Right: No electricity was required for this early-1900's version of a sanding machine

Contractor Sid Galliford bought his first work truck in 1923 — a Ford Model T. Right: No electricity was required for this early-1900's version of a sanding machine

It didn't take too long for floormen to try to find an easier way to smooth the floor. A.J. Beckett, founder of the company that is now Beckett Bros. Floor Co. in Oklahoma City, Okla., invented and patented a machine that would scrape the floors. "It had like a 200-pound weight on the front of it and a knife edge rather than an abrasive grit," explains Steve Beckett, A.J.'s grandson and now president of Beckett Bros. "Two men could scrape a 1,000 square-foot house a day and get it slicker than a sander will." The timing of the invention, which received its patent in 1924, didn't lend itself to be a big money maker, however: "He sold some of them," Beckett says, "but they issued the patent at about the same time they came out with electric sanders."

Not long afterwards, the whole country came to a screaming halt as the Great Depression struck. "Those of us who didn't live through the Depression don't realize how tight things were back then," Beckett says. "My mother always talks about how during the Depression my dad went out to sand this one room in a lady's house. They were all at home praying that we'd get more work. When the lady saw how well he did the one room, she had the rest of the house sanded." Galliford recalls, "My father bought lumber from a company in Toronto. My father used to pay him when he could, and when he couldn't, he just didn't. That's how he fed his family."

Going to War

All debts were paid off quickly when the country went to war, and the entire manual workforce joined together in the collective "war effort." All materials and labor were controlled by war "priorities." Jack Coates of Golden State Flooring Company remembers that the war caused a shift in the type of flooring used in the San Francisco area: "Part of the history of wood flooring out here was that prefinished flooring became prominent during World War II," he says. "The patriotic reason was that we were building a lot of housing for shipyard workers and defense factory workers who came from around the country. We shipped carloads in for this barracks-type housing. But the real reason that the wood flooring industry wanted to make prefinished flooring was that the OPA— Office of Price Administration — had fixed prices on things so people couldn't profiteer during the war. So, all businesses found another way to profiteer. By making prefinished flooring, they said it was a different item and the price wasn't fixed on it, so they were able to get a better price on their product."

Back in Toronto, Sid Galliford found that his company had been essentially commandeered by the government to lay maple factory floors — 24 hours a day, seven days a week. "If he knew somebody who was a floor sander and he was enlisted to go in the army, my father would shove him into floor laying. If he quit, he went back in the army," Fred Galliford explains. "When they laid a floor during the war they figured it out by the acre. The factories were so big that if you were on a job, you were there for two or three years. It was all cut by hand with hacksaws and panel saws for the heavier stuff." Galliford still has a sanding machine bought by the government for his father during the war, as well as then-precious gas coupons given to his father because he was doing war work.

Louis Armstrong, a retired Memphis-area contractor, had gone to Memphis in 1941 to work for a friend in the wood flooring business and made $1.50 a day for his work; his employer was paid 13 cents a foot for furnishing, installing, sanding and finishing the wood floor. When the war came, Armstrong worked building the naval base north of Memphis in Millington and made $1.25 an hour working 10 hours a day, seven days a week. Although sanding machines were in use in the '40s, the job site still involved heavy physical labor.

Hard Labor

"Back then, I could've laid a room with a hatchet and hand-saws before workers today got all their lines and things hooked up," says Armstrong, who at the time was laying the popular 1 1/2-inch strip flooring. "We had a hatchet, hand saw, hammer, pry bar, a string to line it up with and a little block plane —that's all the tools we had. We carried them in a nail keg. I would go to the shop every Monday morning and pick up 100 pounds of nails."

Tony Fidance started in the wood flooring business with his brother-in-law in 1939 at Dominic A. DiFebo and Sons in Wilmington, Del. "When we started,there was no machine to do the nailing. We had to hand nail each board, bent over with a hammer all day and be sure not to hit the tongue," he remembers. "We'd lay another nail on top to push the head back in, kind of like a nail punch, so when you pulled the next board up it would go in tight. The cut nails were in some kind of an oily finish and your hands would get black through the day. It was hard work, but I was the better for it; it kept my body in shape. I don't believe that I'm 80!"

In the Louisville area, where John Bast Sr. was working, the 5/16-inch square-edge, face-nailed flooring was popular. "In 1947, I used to sit on my little tail and pick up and drive 1-inch nails by hand, then you had to set that nail," he says. "I could drive 38 nails a minute, and I was slow. I could set 115 nails a minute, and that was good. The hardest part about it was that in the wintertime it was cold sitting on that floor and trying to pick up nails. Sometimes we would take a bundle of aces — back then you had a coal stove in the basement — well, those aces used to get burned up! I put many of those in to warm the house up a little," he confesses.

"Heat was a problem — it was cold!" recalls Fidance. "I can remember my hand around the hammer handle —when I released it, my hand was still like it was wrapped around the handle. We used to work no matter how cold it was." Lack of climate control certainly didn't help the situation with the subfloors: "We had horrible subfloors to lay over in those early days," says contractor and now consultant Jack Stuart. "They were 1-by-6's laid on a 45, and they were usually all curled up and rough."

The tool of choice for driving the nails varied from region to region. Especially down south, installers such as Armstrong used a hatchet similar to a roofer's hatchet, with the head set at an angle. Others used big straight-claw hammers — a 16-ounce hammer for 3/8-inch flooring, or a 20-ounce hammer for 3/4-inch. "Here in the Northeast, my uncles and my father didn't get Powernailers until probably the late '50s, whereas in other places they were using them earlier. These were the old timers who were stubborn," Price says.

The building shown in this photo, taken around 1913, is still in use by North Branch Flooring Co.

The building shown in this photo, taken around 1913, is still in use by North Branch Flooring Co.

"When he learned how, a good floor layer could lay 600 feet a day with a hatchet and case nails," Armstrong says. "I've done it a million days." Men that skilled didn't change over to nailing machines easily, says Armstrong's son, Coley, who learned the trade from his father in the '50s. "They could lay more floor for years with a hatchet than they could with the Powernailer, because it took some getting used to," the younger Armstrong says. "The machines took a long time to take off here; the guys were used to that hard labor. Then when the guys my age came along, we didn't want to work that hard."

"I remember buying my first Skilsaw in the '50s," says Galliford. "My father said I was crazy and it was too much money. He didn't believe in it, but I figured I needed some speed — they used to pay by the foot."

The boilers being installed in this photo at North Branch Flooring Co. are no longer in use.

The boilers being installed in this photo at North Branch Flooring Co. are no longer in use.

Mixing it Up

After the hand-nailing and sanding process, the floors were grain-filled with homemade filler. Unlike most fillers today, the grain filler of years past actually filled the grain of the wood, giving the appearance of a perfectly flat floor. Its recipe varied from contractor to contractor, although linseed oil was a constant. "We used linseed oil, Japanese driers, mineral spirits and Spanish whiting, then color if you wanted it," says Bast. "We were down on our hands and knees when we filled the floor. We didn't have knee pads like you get nowadays — what we did was we took an old pair of pants and cut the legs off and rolled them up like a doughnut. We would take string waste and put that down in the hole of the doughnut, and that made like a knee pad. Then when you crawled around on the filler, it built the material up. Every time we did it, we'd take shellac and shellac 'em."

The filler was rubbed into the wood by hand with a mesh-type cloth and then rubbed off with an old feed sack or burlap material. Stuart recalls that they used to buy linseed oil direct from the manufacturer in 50-gallon drums and that in the wintertime, they added gasoline to their concoction to make it dry faster. At Beckett Bros., the filler was wiped off while still wet: "If you left any on, the next day it was like rocks,"recalls Beckett.

After filling, floors then were typically finished with two coats of shellac, depending on the region. Coates at Golden State remembers the days when they had wooden barrels of shellac. "You'd roll a wooden barrel out to the guy's shop, put it up on a stand and he'd draw the shellac off," Coates says. Between coats of shellac, the floormen went back down on their knees to hand sand the floor. "Between coats we swept it up with a dust brush, which never really got all the dust up,"says Fidance.

After the necessary coats of shellac were applied, in most parts of the country they were typically followed by wax, which was rubbed in by hand. At Beckett Bros., a ball of hot wax was put in an old t-shirt, which allowed the wax to ooze out onto the floor, Beckett says.

Once the wax was applied, it had to be polished, explains Ralph McSwain of McSwain's Hardwood Floor Store in Cincinnati: "The wax was buffed in with an iron weight — like a heavy block of metal with a pad on it — on the end of a pole with a hinge on top of it," he says. "You would stand in the middle of the room and sling it back and forth from one position."

Bill Price remembers that they progressed to using "hot waxers" to wax the floor. "We had a gallon-sized, cast aluminum pot on the buffing machines, and you'd scoop the paste wax into that pot," he says. "There was an electric coil that heated and melted the wax and a small chain from the handle of the machine that when you pulled it, it squirted the wax out the center of the buffer. You'd use it with a wax spreading brush." A polishing brush would then be used to finish up, he says.

Although habits and timing varied throughout the country, as the '50s progressed, finishes changed, also. In some areas, shellac and varnish were used without a wax coat, or several coats of shellac were used without wax. Later in the '50s, lacquer came on the scene, which created a whole new job site, says Fidance: "With the Fabulon, in the wintertime we had to open the windows. It was 30 degrees out, but we still had to open them, because if we didn't, we got high." Another time, he recalls, they didn't realize a pilot light was on in the stove and they barely got out of the house unscathed as the fumes ignited, burning the home's interior.

Louis Armstrong still owns a hatchet he used to install flooring during his Memphis-area contracting career, which started in 1941.

Louis Armstrong still owns a hatchet he used to install flooring during his Memphis-area contracting career, which started in 1941.

Changing Times

Finishes weren't the only changing aspect of the job site. Construction had changed in the country, and, depending on the region, plywood or concrete were being used as the standard subfloors. Because concrete was so common in the southern United States, the strip market there was dwindling. Claude Taylor started his career in the industry with E.L. Bruce Co. during this period. "When I got into it in 1949, our market was quickly becoming the middle west and northern states," he says.

"One of the things that really helped change the floorcovering industry at that time was in 1955 Harris Manufacturing started making the Bondwood parquet, and then that grew," explains Warner Tweed, who worked for Harris for 13 years. The parquet could go directly on concrete at a time when the only way installers knew how to lay strip over concrete was with screeds. The parquet, on the other hand, was laid directly down with cutback asphalt adhesive. "Because of the price of Bondwood, it would still go in the lower price homes and be competitive with vinyl tile, which was big in those days in the slab markets. They sold millions and millions of feet of it for apartment buildings in New York, Chicago, L.A., Philadelphia and Baltimore," he says. Coley Armstrong says that in the Memphis area, roughly 70 to 80 percent of the flooring put in from the late '50s to early '70s was Bondwood, for which they charged about 32 cents a foot for installation, sanding and finishing in the early '60s.

Some of the earliest sanding machines and a floor waxing brush are on display at McSwain's Hardwood Floor Store in Cincinnati.

Some of the earliest sanding machines and a floor waxing brush are on display at McSwain's Hardwood Floor Store in Cincinnati.

Building Mania

The building boom of the post-war era was a craze of activity that changed how installers did business. "Back when I started into wood flooring, right after the second World War, everything was production, you know, a push in a big hurry to get it done," says Bast. "They quit doing border work and just went for production — they had so many houses to do! You just kept going, going, going. You lost your good mechanics because you weren't doing anything fancy. When I came up, I didn't have the opportunity to do all the border work my dad did."

Up in the northeast, Bill Price found a similar situation. "My brother and I would have to sand and finish two ranch houses a day with two coats of finish for my father to make any money — or sand three a day to make any money," he says. "Obviously, the sanding was not the kind of sanding that people do today. Back during the '50s, everybody was probably finishing with 60 grit. We'd just go up and down the street, sanding and finishing two houses a day. You learned the hard way and you had to get it done. Everybody had to produce; that was the way it was."

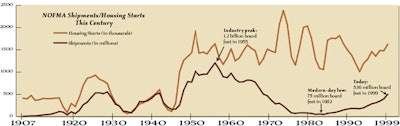

The building boom was so strong that in 1955, wood flooring reached its peak production at more than 1.2 billion board feet that year. The building and wood flooring boom extended to all segments of the states, nowhere more so than on the West Coast. "1955 was the boomingest year in the history of the country," recalls Stuart. "There was an outfit in L.A. that was doing 50 houses a day in one subdivision. I drove all the way down there to see it. They had a great big warehouse where freight cars would come in, and they'd load all the trucks at night. I visited this guy in charge, and he said that to sign a contract for a subdivision, they had to sign a penalty clause that said if you fall behind, they notify you in writing, and if you aren't caught up within three days, they back charge you so much per house per day. He received a telegram on Friday that said if he wasn't caught up by Monday evening, he would be charged $15 per house per day — that was a lot of money then. His superintendent had a book of all the floor layers in southern California, and he called up every floor layer he could get his hands on. On Saturday they laid 150 houses in one day — it's unbelievable. There's nobody today who could even deliver the flooring to those jobs."

Market Free Fall

Few people in the industry are unfamiliar with what happened the following decade: In 1966, the Federal Housing Authority, along with other lending agencies, began approving carpeting as part of a 30 year mortgage. Hardwood floors were no longer a necessity, and both builders and home owners jumped at the chance to escape from the hassles of wood floors. A combination of high maintenance, cheap products and too much job-site time all contributed to the crash of the wood flooring industry.

"I still claim that part of the downfall of the wood flooring business was that in the postwar era, everything was so much mass housing. It had to be cheap," Coates says. "The cheapest way to do a floor was coat of lacquer and a coat of varnish, but those finishes never last. Most of the products were cheap. That's part of the reason that they approved carpet so readily. The builders couldn't wait to get rid of the hardwood floor guys." In September of that year, Golden State did one half of what it had done in May. "I remember working two to three days a week because we didn't have much to do," he says.

"I grew up on wood floors, and my mother would wax the floors every week," says Bruce Nesmith, general manager of Buchanan Hardwood Flooring in Aliceville, Ala. "A couple of times a year, she'd strip the wax off them and rewax. It was a lot of work and was time-consuming. When kids would come tearing through the house, they'd mess up the wax on the finish. She was thrilled at the idea of putting a carpet down so she didn't have to wax floors anymore. It wasn't that she didn't like hardwood floors; she didn't like to wax hardwood floors," Nesmith recalls.

Wood flooring companies took different approaches to try to keep their heads above water. Most simply went out of business.

"We went from 30,000 feet a week to 4,000 a week in six months," says McSwain. "Most companies went broke; I went in the carpet business.

Most of the builders changed midstream. We had 264 builders at that time and almost every one of them went to carpet. A lot of good friends went down the tubes. Most of the small mills went out. It doesn't seem possible that it could happen now, does it?"

Up in Toronto, Galliford & Sons took a different approach. "Everybody told us we should go into the tile business, yard goods, broadloom — we didn't want to do that," Galliford says. "We got into the insurance companies —floods and fires and that stuff. That's how we survived all that. I used to sit and watch TV, and if there was a fire at night, I'd say, 'I'll be there in the morning.' I was basically doing every fire in Toronto in those days."

"It was a period in which 90 percent of the industry went off line," says Ray Spivey Sr., chairman of the board of Cumberland Lumber and Manufacturing in McMinnville, Tenn. "When 90 percent of it's killed, you go through some tough times. We pulled through with great difficulty. When I became president of the National Oak Flooring Manufacturers Association in '75, '76, we were down to 16 members. At one time before that we had somewhere over 100 members." Claude Taylor, president of NOFMA from 1991 through 1992, also remembers those tough times. "I think five NOFMA presidents in succession went broke while in office," he says.

"We were a little bit diversified in that we manufacture dimension parts— cabinet and furniture parts — in one of our plants," explains W.T. "Bill" Mullican, secretary/treasurer of McMinnville, Tenn.-based McMinnville Manufacturing, one of the few remaining charter NOFMA member mills. "We relied heavily on that at the time, and we still do to a lesser extent, but now we've flip-flopped more into flooring."

In some areas of the country, consumers quickly became dissatisfied with the low-quality carpeting that had displaced wood flooring. "I remember going out to deliver flooring to a job and the builder was there," Coates says. " He said, 'I hope you appreciate this job, it's probably the last job you'll do for us; we're going all carpet.' I took great offense and I remember that builder coming back for wood flooring two or three years later."

For most parts of the country, however, the bite of carpeting had a sting that lingered well into the '70s, as it did in Beckett Bros.' Oklahoma market. "Through the '70s we'd have a lot of builders and realtors who would tell our customers that if they put a wood floor in their house, they'd lower the property value," says Beckett.

Evolution

As the wood flooring industry whimpered back to life, it evolved into a new type of business. "I still claim that was the best thing that ever happened to the wood flooring industry," says Coates. "We realized that we could do other things to upgrade the product. We had been busy selling so much volume — I remember Golden State took in 200 carloads of flooring in about 1950, and we probably didn't make a whole lot of money. Everything was so cheap. When we came back we were a little more careful; we sold upgrade product… That transition made us all better because we were just volume producers in the old days."

"In the mid-'70s, our demand started growing for hardwood floors," remembers Lon Musolf, then a contractor in the Twin Cities area of Minnesota. "Then we faced the problem that most of our labor had left. Most mechanics had gone into other industry and trades. There was a big need for training programs, and that's about the same time NOFMA started their schools." The different wood flooring market also had an effect on what it meant to be a wood flooring contractor, he says. "When they came in with the paperface and pattern floors and inlays and laser cuts, it got very interesting, so labor was much easier to keep. It wasn't so repetitious, so that made a big difference in our labor situation," he says.

Consumers were now faced with a more interesting market, as well. Polyurethane finishes offered a durable, low-maintenance finish option. And consumers chose from an entire spectrum of options, from regular strip to parquet and increasingly common engineered and prefinished flooring. The "laminated" parquets that had grown so popular in the '50s had helped give rise to a new type of product — laminated strip. "The real success to that was in getting a better adhesive, because the old black cutback adhesive didn't hold that well," says Tweed. Newer chlorinated solvent adhesives performed better.

The industry bottomed out in 1982 in the midst of a general recession. Only 75 million board feet of flooring were shipped that year, according to NOFMA statistics. Since then, the numbers have made a steady, impressive climb, presently at more than six times the level they were in the grim early '80s. The resurgence of wood flooring led to the creation of the National Wood Flooring Association, which began in 1985 with the mission of increasing the awareness, sales and professionalism of the industry.

Today's market has diversified to an extraordinary level. Consumers choose from a multitude of finishes, including the waterborne finishes that appeared on the scene in the '80s. A home owner can select an exotic species from almost any far reach of the globe, oftentimes with the options of unfinished or prefinished, engineered or solid, or even floating. Even middle-class home owners now have the option of any number of borders, inlays or specialty patterns they can afford. The products are installed by expert wood flooring specialists, who arrive at the job site with a veritable vanload of equipment, pneumatic tools and supplies. It's a far cry from carrying everything in a box on a streetcar, but most people in the industry today wouldn't have it any other way.