The author (left) and project manager Jim Lotspeich of Builders West Inc. review plans after floods destroyed the home's existing wood floors.

The author (left) and project manager Jim Lotspeich of Builders West Inc. review plans after floods destroyed the home's existing wood floors.

Here in Houston, where hurricanes hit on a regular basis, if you do wood floors, it's a guarantee that you'll end up dealing with the aftermath of floods. Our own wood flooring showroom here in Houston has been under water six times, and as I write this we're just starting to recover from the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. The first week after Harvey hit, nobody was out and about, and out of about 30 employees, only two or three could make it in to the office. We tore out baseboards and wet insulation and threw out all the things that were ruined. Once the water receded, we got fans and dehumidifiers on our floors. Now our own floors are in good shape—they survived being flooded again—but we haven't put the showroom back together because we're so busy trying to finish up the work we had in progress before the hurricane and bidding all the flood work. We've heard from people we installed floors for up to 35 years ago, and of course everybody wants something immediately.

Here's how we go about dealing with all the wood flooring work after yet another flood situation.

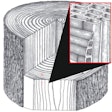

After a hurricane there are groups of people who cruise neighborhoods like gypsies offering to take out flooring for $X per square foot, and homeowners are in a rush to let the drying process begin. When we get there, we see all sorts of interesting things, like the subfloor at left (I'm not sure who did that, but I hope it was a carpenter and not a wood floor guy). This home also had Houston's trademark tar-and-screed subfloor (on the right) in an area with an addition. The plywood subfloor was directly over joists, so we would potentially be able to dry that out, rip out the shims and redo the necessary areas to have an acceptable subfloor. For the areas with the screeds and tar, we would want to take that down to a clean slab and let that dry before installing a new wood floor.

After a hurricane there are groups of people who cruise neighborhoods like gypsies offering to take out flooring for $X per square foot, and homeowners are in a rush to let the drying process begin. When we get there, we see all sorts of interesting things, like the subfloor at left (I'm not sure who did that, but I hope it was a carpenter and not a wood floor guy). This home also had Houston's trademark tar-and-screed subfloor (on the right) in an area with an addition. The plywood subfloor was directly over joists, so we would potentially be able to dry that out, rip out the shims and redo the necessary areas to have an acceptable subfloor. For the areas with the screeds and tar, we would want to take that down to a clean slab and let that dry before installing a new wood floor.

Salvaging our showroom floors

People are always surprised when they find out how many floors we are able to save after a flood. Our showroom floors are a good example; I mentioned that our showroom has been under water six times. Three or four of those times were from hurricanes, while the other times were from heavy rains. Unfortunately, the only storm sewer drain on our street for a mile or so in either direction is right in front of our building, so if we get a really intense rain we're always worried about water backing up. Our front door and showroom are approximately 2 feet higher than our parking lot, so when heavy rains come, we're sandbagging, and when it starts flooding, I put on my waders to check the drain. During the worst of Harvey, I was out all night in water up past my waist just trying to clear that drain and make sure the water subsided as quickly as possible.

Despite all our floods, we still have the same wood floors in our showroom and offices—the flooring is end-grain mesquite glued directly to an epoxy-type moisture barrier over the concrete slab. During Harvey, that wood floor got as much as 6 inches of water on top of it. In the hallway for the offices and our mailroom, we have a ¾-by-7-inch long-length engineered oak plank floor glued to the same moisture barrier over the concrete slab, and that's been under water three times. For both of these floors, as the water from Harvey receded, they looked like hell, full of sediment and debris, but even the plank hadn't buckled or even cupped. We wet-mopped them just to try to get all the junk off, then dried them by putting fans and dehumidifiers on them. Our showroom is about 1,000 square feet, and we had about four or five of the carpet-drying fans and probably three dehumidifiers running 24/7 for several weeks.

Both of those floors had burnished oil finishes, and once they dried to typical moisture levels, we just buffed another coat of oil on them, and now they look fine.

In my office I have a ¾-inch antique solid oak plank floor glued to the slab, and that's been under water probably six times. After Harvey it buckled. When we installed it, we had glued that floor to a sheet-type moisture barrier that was glued down with a water-based adhesive. With the flood, the flooring remained adhered to the barrier, but the barrier adhesive failed, so now, even though we dried and flattened the floor, it is essentially a floating floor. When we get time, we'll replace it.

We looked at this job maybe only one and a half weeks after the hurricane; I was amazed they had made so much progress. For the area on the left, we will end up chipping out all that tar and what we call patch so we are down to the original slab. Then we will do our usual slab prep with a self-leveling underlayment and a moisture membrane before shooting a new plywood subfloor to the slab. The area on the right had a plywood subfloor; the slab just needs to dry before we start installing.

We looked at this job maybe only one and a half weeks after the hurricane; I was amazed they had made so much progress. For the area on the left, we will end up chipping out all that tar and what we call patch so we are down to the original slab. Then we will do our usual slab prep with a self-leveling underlayment and a moisture membrane before shooting a new plywood subfloor to the slab. The area on the right had a plywood subfloor; the slab just needs to dry before we start installing.

Looking at clients' hurricane floors

Right now I'm spending the majority of my time doing estimates for work caused by Harvey. When I first visit the homes, many still have wet floors, and there are still wet belongings everywhere. For others, demolition companies have already taken out everything in the homes, including the wood floors, so we're just talking about replacement.

For homes that still have their wood floors, we are able to save some of them. The first question is: Are they buckled? If they are, they probably aren't worth trying to save.

We also have many clients who ask us about mold and mildew. I always tell them I can't counsel them regarding mold and mildew concerns—they need to talk to a mold remediation company about that. The local news here has also exploited several cases of flesh-eating bacteria in the water. If the client has any of these concerns, why take a chance? Many of our clients have the resources to pay for a complete removal and replacement.

This is a typical plank floor over screeds with plastic on top of the screeds; in this area it's common to use plastic over screeds to protect the wood from nuisance leaks like those from an icemaker. In situations like this, though, that works against us, because the plastic acts like a glass ceiling. Although we can save many cupped floors, for a buckled floor like this it doesn't make sense to try to save the floor.

This is a typical plank floor over screeds with plastic on top of the screeds; in this area it's common to use plastic over screeds to protect the wood from nuisance leaks like those from an icemaker. In situations like this, though, that works against us, because the plastic acts like a glass ceiling. Although we can save many cupped floors, for a buckled floor like this it doesn't make sense to try to save the floor.

For clients who don't have those resources, we'll try to save the floor for them when we can, and over the years we've been able to save floors that have been severely cupped. For example, we had two employees with strip oak floors that flooded with 4 or 5 inches of water during Harvey. These strip floors were installed in a way that seems unique to Houston (I think it might be because of our petrochemical industry). Back in the old days, long before my time, the roofers used to pour tar on the slabs and put 2-by-4 screeds down. Then the carpenters would install the wood floor, and the flooring companies would sand and finish them. The employees I mentioned had these sorts of older strip floors over screeds. They didn't have flood insurance and couldn't afford to move out of their homes, so we dried out their floors. Of course, those screeds create a space that can fill up with water—but at the same time, that space enables you to inject air underneath the floor and dry it from both the top and bottom. With floors like that, if the client wants to save the floor, we remove several rows of planks on the sides of the floor, since the screeds run perpendicular to the floor. We use special injection fans that are high-volume—much more powerful than your typical carpet-drying squirrel-cage fans—to create air circulation through the ingress and egress in the screed space. Then we use fans and dehumidifiers to dry the flooring out from above.

For both of these floors, they dried out so well that we didn't even have to buff and recoat the floors, much less sand them. In fact, for one of them, the FEMA adjuster came and said, "Your floors look perfect, so we're not going to give you any money." That seems like an injustice, but it does show how well some of these floors can recover after having standing water on them.

Whether they have urethane or oil finish on them, the longest we've found it has taken a floor to dry completely using the drying equipment has been about three weeks. Some local flooring contractors like to rough-sand water-damaged floors to get the finish off and open the pores to enhance the drying process, and we used to do that when we knew we would be sanding and refinishing a floor after it dried. But if the floor's really cupped, you take off quite a bit of wear surface just trying to rough-sand the finish off. To me, you're just wasting wear surface, so why do it?

The most difficult floors to save are those with plywood under the wood floor, because it's virtually impossible to dry that plywood out. For a job where we had a floor on top of plywood on top of screeds, I can dry the floor, and I can dry the screeds, but I can't dry the plywood, so that floor is coming out. Typically we do our own demolition work, but we're so spread out right now that we're asking our clients to get somebody else to tear out their flooring. It doesn't require a lot of expertise, so after they remove the flooring, we'll come in and take it from there.

If we're doing a job where the wood floor has been destroyed, we'll insist that the floor goes down to the bare slab and dries for at least two or three weeks with the air conditioning and/or the fans and dehumidifiers running. Once we think the job site might be ready, we'll test the studs with moisture meters to see if we are getting normal readings before we'll think about bringing in our wood.

For smaller flooded areas from things like a plumbing leak, we use these drying mats manufactured by Dri-Eaz that draw the moisture out of the wood. They are perfect for a situation like this where the floor is drastically cupped but not buckled, and it's contained to this area. They aren't really practical to do a whole house but are perfect for this scenario; I describe it like a rifle as opposed to a shotgun approach.

For smaller flooded areas from things like a plumbing leak, we use these drying mats manufactured by Dri-Eaz that draw the moisture out of the wood. They are perfect for a situation like this where the floor is drastically cupped but not buckled, and it's contained to this area. They aren't really practical to do a whole house but are perfect for this scenario; I describe it like a rifle as opposed to a shotgun approach.

Saving smaller flooded floors

Apart from natural disasters, we have created a niche for ourselves dealing with smaller water damage like that from a plumbing leak or an ice maker leak. We have drying mats (ours are made by Dri-Eaz); you put them down on the floor and connect them to a vacuum pump. They have such a strong vacuum that we have videos where you can actually see the moisture being pulled up through the pores of the wood.

These mats are a more targeted approach for a smaller area—if I have a whole room that's flooded, I will try to contain that room, not leaving it open to the whole house, and use fans and dehumidifiers to dry it out. But if I have a smaller area, these drying mats are very effective. We'll rent them out by the day, and sometimes we'll have five or six systems out on one job.

I had a fellow contractor call me one day, and he asked me, "Greg, I saw this on your website—aren't you cheating yourself out of your water damage repair jobs?" I told him that if you think about it, I can make hundreds of dollars a day with these versus being down on my hands and knees tearing out, replacing, sanding and finishing. Which would you rather do? These systems are making money for us while we're doing other things.

Another benefit to drying water-damaged floors is that it's a better service to our clients. Many of the homes we work in have priceless art and antiques. We spare those clients the hassle of having to remove those and temporarily relocating. So if we can dry out the floor for a fraction of the time and the cost—and spare everyone issues with logistics—why not?

With this equipment, we've become like a one-stop shop for customers with these issues. Typically they might have otherwise hired remediation companies, and those tend to leave their equipment on a job for only three or four days before the insurance company tells them to pull it off; mainly they just want to tear out the floor. We'll come in and dry the floor, and then we'll buff it or touch it up—whatever's necessary. They don't have to look for another contractor.

Of course, another benefit of this work is that we are saving natural resources. If the floor is salvageable, I just hate to see the waste.

Dealing with insurance companies

When doing any sort of flood work, we won't work directly for an insurance company. If a client's insurance company has questions about my approach to a job, out of respect for my client, I will respond to them, but at the end of the day, I look to my client for payment.

Many of the insurance companies down here are under the impression that if a floor hasn't flattened out after drying for two or three days, it never will. The insurance companies will call me and say, "We aren't used to having drying machines on the job for so long," or they will tell me the drying estimate is too high. I just respond, "Fine, then pay someone to remove and replace it; you'll pay three times as much money." When they argue that our bid for replacement is too high, I tell them, "I know it doesn't fit into your spreadsheet or in your estimate program, but that's what it costs."

This is the first hurricane where we've found that even when we say the floor is going to settle down (sometimes without us even having to dry it), the insurance company adjusters are insisting we give them replacement costs so they can write that check. It's strange.

Looking ahead

By now we're past those initial weeks when traffic was gridlock and our city looked like a Third World country, with mountains of personal belongings and trash piled up high on the streets. People aren't sitting around waiting for someone to help them, they're getting things done. Traffic is back to normal, maybe even a bit lighter, as we had reportedly a half a million vehicles that were totaled in the flooding. For many months to come, we'll be doing our part to try to get our customer's lives—and our own business—back to normal, too.

Meanwhile, back at the office ...

That isn't glossy finish, that's standing water in our showroom on our end-grain mesquite floor in this photo. At this point, the water isn't that deep, but it's the first inch of water that does all the damage; the rest is academic.

When we have a heavy rain, we put sandbags by the front doors to our showroom. When it's really flooded, like during Harvey, the big trucks driving by on the street create a huge wake and splash against the entry.

In the top photo you can see the water line where the flood reached on the door trim. That's an engineered domestic white oak plank; once it dried out we were able to clean it and then buff in a new coat of burnished oil, as you can see in the photo on the bottom right.

Harvey hit on Saturday and we flooded. We started cleaning up later that day, but then we flooded again on Sunday. Once the water was gone, we used dehumidifiers and fans to try to dry things out as quickly as possible. You can see the debris and film on our end-grain mesquite in the photo on the top right. The middle and bottom photos show what the floor looks like now after a new coat of oil. |

See more from Schenck and Company:

Barn Beams Become Custom Flooring at Texas Ranch

Private Owner's 'Car Museum' Features Rotating Wood Floor

Big Winners: Wood Floor of the Year 2013

A Portfolio Helped Launch This Company into the Design World

Photos: Schenck and Company Wins Texas ASID Award For Flooring