Tony Martin was expecting tumbleweeds. It was the vision of Arizona he had before he moved to Phoenix from Pegueros, Jalisco, Mexico, at the age of 18 with only a few dollars in his pocket. But if there had been tumbleweeds rolling along the busy metropolis streets, Martin might not have even noticed them—he was busy looking up. “I saw a big city with a lot of potential; sky’s the limit,” he recalls.

“I was like, ‘Well, I think I can do something here.’” Now 43 and the owner of Excalibur Hardwood Floors, one of Martin’s latest career milestones was painting and coating the court for the 2021 NBA finalists Phoenix Suns—a hardwood floor viewed on televisions around the country where he arrived 25 years ago “with more dreams than clothes.” It was a level of success that was hard to envision in the early days when he was sleeping on the streets and park benches, but eventually, unlike the tumbleweeds, he found it.

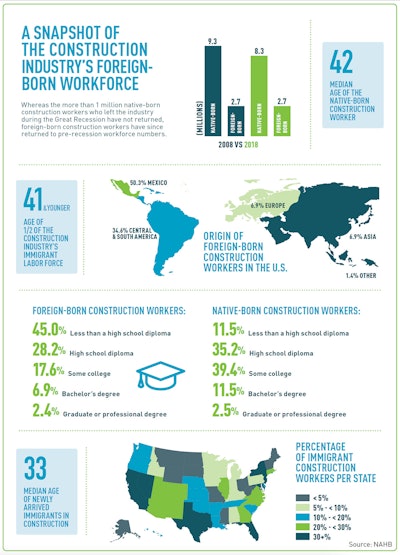

30% of the construction workforce

Martin’s journey toward the construction industry after arriving in the U.S. is not uncommon. Today, immigrants make up approximately 30% of the construction workforce, according to the National Association of Home Builders. In the flooring industry, that percentage is even greater, as NAHB estimates immigrants made up approximately 40.2% of the carpet, floor and tile installers and finishers labor force as of 2018. In an industry that is facing a severe labor shortage crisis, immigrants play a critical role in making the trades run.

Wood flooring itself is a uniquely challenging trade. The immigrant journey to hardwood flooring success includes additional uphill climbs. And yet, with hard work and determination, many immigrants have forged a path for themselves despite those challenges. WFB spoke with wood floor pros who immigrated to the U.S. about the challenges they’ve faced and the successes they’ve had in the industry. Every foreign-born wood floor pro’s path to the industry was different, and none of them were easy—but each proved that talent and passion within the industry is very much alive.

Tony Martin came to the U.S. at 18 with only a few dollars in his pocket.

Tony Martin came to the U.S. at 18 with only a few dollars in his pocket.

Today, Tony Martin's gym flooring work can be seen in high schools and colleges across Arizona.

Today, Tony Martin's gym flooring work can be seen in high schools and colleges across Arizona.

Starting out: ‘I was hungry to do something’

The availability of labor opportunities in hardwood flooring has long been a draw for immigrants in search of work after arriving in the U.S. Martin found it through a connection he had while working on ranches with horses and milking cows. He was taking any job he could find at the time, but he was particularly attracted to a gym flooring opportunity; he had some experience working in his uncle’s wood furniture store when he was younger. “I was hungry to do something,” Martin says.

The moment immigrants set foot in the U.S., a clock begins ticking to find employment, according to Anthony Nguyen, 30, of Lynnfield, Mass.-based Eco Wood Flooring. “It’s basically do or die,” says Nguyen, whose parents immigrated to Northern Massachusetts from Vietnam in 1990, a year before Nguyen was born. “Traditionally, the male would always go into the hardwood flooring business because there was no license needed, there was not much education needed; it was something where you just started and made a living out of,” Nguyen says.

Jon Capalnas, who founded Niles, Ill.-based A-American Custom Flooring Inc., worked janitorial jobs in Chicago after emigrating from Romania in 1985, according to his son, Jonny, 32. Jon’s flooring career began with someone asking whether he did flooring, Jonny says: “And being the ambitious and kind of courageous type that he is, he said, ‘Of course I can do flooring!’” That same spirit eventually led to the start of a distributorship in the early 1990s with the purchase of a 1,000-square-foot facility, which over the years grew into the company’s 300,000-square-foot facility and 20,000-square-foot showroom operations in the Midwest, with branches in Chicago, Niles and Honolulu.

Stephen Le, 52, of Burlington, Vt.-based Ecowood Floors LLC says there were limited options for immigrants when he started in 1992. “Let’s say you’re Vietnamese in Boston; you’re either in the flooring business, the dry cleaning business, the nail salon business or the restaurant business,” Le says. “So you have about four choices, either or.”

Before he arrived in Boston, Le and his family were among the Vietnamese refugees forced out of Vietnam in the late 1970s because of their Chinese heritage. They arrived in Hong Kong in 1978, and two years later they were separated—his parents were sent to the U.S. and 10-year-old Le and his sister were sent to Canada, where Le remained until reuniting with his family in 1992.

“People don’t understand; they say ‘Oh, you’re going to come to this country and take away jobs’—but no, everyone who comes to this country, they’re starting from scratch,” Le says.

Family connections to the trade

Family is an important factor for many who’ve immigrated to the U.S. and began working in the trade. Le joined a cousin’s hardwood flooring business after arriving in Boston. Hakob Karapetyan, 33, from Yerevan, Armenia, followed his older brother, Levon, to work at Levon’s thriving San Francisco-based company, Hayasa Flooring Design. Levon’s initial success in the country allowed Hakob time to attend UC Berkeley, where he developed a business acumen he would later pair with Levon’s installation expertise, taking the business to a new level. “So that’s how we were able to grow even more,” Hakob says.

While working doing cell phone screen repairs in Marietta, Ga., Helen Altamirano, 33, who emigrated from Matagalpa, Nicaragua, recalls getting occasional glimpses into a relative’s hardwood flooring business and feeling like that was where the action was—and where she wanted to be. “I was like, ‘Don’t pay me a penny, I will go over there just to help you with the hardwood floors!’” she recalls. “And I just fell in love with the job. I was like, this is my work.” She went on to establish the successful Sinbad The Enchanted Floors LLC.

Family also drew Daniel Ardelean, 46, of Niles, Ill.-based Daniel Flooring and Construction Inc. to the U.S., where he’s built his business by focusing on high-quality materials and service. But there was a time when it looked like he might have to give it all up. Born in Romania, Ardelean joined his brother in the U.S. in 2003 to work for his brother’s construction company as a flooring contractor. However, a few years later, Ardelean’s brother was killed in a car accident. Suddenly, Ardelean was on his own. “I got a little scared,” Ardelean says. “I thought, ‘OK, I’m in the middle of nowhere now, so what should I do?’ It was a very big question for me.” Little by little, he built his flooring company and found his way.

A refugee from Vietnam, Stephen Le built his flooring business in the U.S.

A refugee from Vietnam, Stephen Le built his flooring business in the U.S.

A major challenge for many: the language barrier

Working with his brother, Ardelean says he was able to simply speak Romanian on job sites. Once he was on his own, the English language quickly became a necessity. “Year by year, I learned,” he says. “I learned from radios, and when I didn’t know a word or something, I wrote it down on paper and I pulled out a dictionary to see what it meant.”

The language barrier is one of the first challenges many wood floor pros who’ve immigrated to the U.S. say they faced. Altamirano took a few English courses while growing up in Matagalpa, Nicaragua. But after moving to the U.S. in 2010 with a degree in engineering, she found speaking the language outside the classroom was a whole different ballgame. Determined to improve, she enrolled in more English classes and also took a customer service opportunity at a local carpet company to practice. “I got used to speaking through the phone to my customers,” she says.

Tony Martin says the language barrier leads many companies to take advantage of those who don’t speak English—it happened to him during his first week in the U.S. when he was building boxes for a tree nursery. “I worked really hard for a whole week under the Arizona sun,” he recalls. But at the end of the week, when it was time to get paid, he was told through a translator that he’d be leaving empty handed: “I was told, ‘Well, you know what, we noticed that one of the saws you’ve been using is not working the way it’s supposed to, so you broke it, so we’re not going to pay you.’”

Martin suspects the employer incorrectly presumed Martin was in the U.S. illegally because he did not speak English (he was, in fact, a legal resident), and thus thought he could take advantage of Martin’s situation. “A lot of people discriminate just because they see you and you look different and you speak a different language,” Martin says.

The discrimination also goes beyond a language barrier. Racism and misconceptions about immigrants can make it more difficult to compete, particularly in a trade dominated primarily by white men, Stephen Le says. Immigrants must seek out additional ways to advance in hardwood flooring, and one of them is certifications, Le adds.

“The only way to compete at the level of this competition is to get yourself education and certification at the national level,” Le says. “So that way you come up to a level of craftsmanship and you have some sort of paper to prove it.” Le says he sees a lack of certifications in the Asian wood flooring community. “I don’t see anybody else with papers,” he says. “I want to be that guy.”

Finding advantages where you can

Like many children of wood flooring pros, Anthony Nguyen grew up being taken along to job sites on the weekends to help out. But as the son of an immigrant who spoke limited English, Nguyen had an additional job along with sweeping up and carrying tools: translator. “My father knew a little bit of English, only enough to communicate terms in his work, such as ‘sanding’ and ‘install,’” Nguyen says. As a kid, Nguyen viewed the language barrier as a disadvantage for his father, who passed away in 2014. But now he sees how his family worked to turn the perceived restriction into an advantage. “It showed the homeowner that this was a small family company; everybody would tell me how cute and well-behaved I was,” Nguyen says. “In a way, I think it really attracted a lot of customers toward my father, because who could resist a little kid helping his father out?”

For Daniel Rios Carrasco, 31, of Denver-based Walnut Hardwood LLC, traditional schooling was difficult. He didn’t finish high school and was later diagnosed with ADHD. But when he moved to the U.S. from Torreón, Mexico, he found that he was able to teach himself English through his study of hardwood flooring. “I was like, ‘Well, I’m going to kill two or three birds with one shot,’” he says. “‘I’m going to learn about business, I’m going to learn about floors and I’m going to learn about English.’” He did most of his studying online, and his method was a fast-track to strengthening all three skills.

Technology has helped open up new doors for communication among employers and employees, as well. Sprigg Lynn’s company, Washington, D.C.-based Universal Floors, which has a long history of hiring and sponsoring foreign-born workers, uses an app to help communicate with employees who speak limited English, many of whom are from El Salvador. “You can speak English into the app and it comes out in Spanish,” Lynn says. “So there’s no reason why you can’t break down the language barrier.” The app on his phone can translate virtually any instructions Lynn needs to give employees. Lynn’s company also goes the extra mile by helping to pay for traditional English lessons for its crews. “Any continuing education that you do for speaking and learning English, we’ll pay for half of it,” Lynn says. “And then once they learn the language, it seems to open up a lot for them.”

Learning a language is about a lot more than simply understanding words, notes Hakob Karapetyan: “In Armenia, we have a really good saying: ‘As many languages as you speak, as many people you are.’ Which means basically, if you speak a language, it means you can understand the culture.”

The immigration process: never a ‘straight line’

Tony Martin experienced hostilities and a lack of housing during his first few weeks in the U.S., but he still considered himself extremely fortunate at the time. When he was only a couple months old, his parents immigrated to the U.S. briefly and obtained residency papers for him at the U.S./Mexico border. “I didn’t have to go through any hoops,” Martin says. For many others, he says, the immigration process can be long, expensive and filled with uncertainties.

“In order to come here, you have to have a good amount of money in your bank account, you have to apply for the visa, which is expensive, and there’s no guarantee you’re going to get it,” Martin says. “So it’s hard … and sometimes it takes 15 years or more to become a resident.”

The journey to becoming a permanent resident in the U.S. can be a bumpy one, says Helen Altamirano: “You have to know that the road will never be a straight line.” Altamirano moved to the U.S. from Nicaragua in 2010 at the age of 22 with her fiancé. But the marriage didn’t work out, and she got divorced in 2013. She was on her own in the U.S. without a green card. “Everyone was telling me very negatively, ‘Oh no, you are just going to get kicked out,’” she recalls. “But I told myself, ‘OK, I will go through the process. I will try.’” Altamirano worked with a lawyer to obtain her green card through her business. “If you work hard and you try to prove that you want to be here and do something for the country … they are very good and they will help you, as long as you are honest with them and you follow their rules,” she says.

Helen Altamirano notes that the immigration journey is “never a straight line”—but says hard work can pay off.

Helen Altamirano notes that the immigration journey is “never a straight line”—but says hard work can pay off.

Altamirano founded Sinbad The Enchanted Floors LLC.

Altamirano founded Sinbad The Enchanted Floors LLC.

Many pros also use sponsorships to remain in the U.S. “Even if you have a legal right to come here to the U.S., you need to have a sponsor, so in case you come here and, God forbid, something happens, you’re not a burden on American taxpayers,” Hakob Karapetyan explains. “We had someone from our close circle of friends who had enough income and could support our coming and sponsorship agreement to prove that if anything happened, they could take care of us.”

As an employer, Lynn has sponsored about 20% of his company’s workforce. “If you sponsor someone, they’re going to be with you for four or five years and you’ll pay them, which is a win-win for both people,” Lynn says. “I want someone to not just have a green card or work permit; we ask them, ‘What can we do to help you get your citizenship?’ And we work toward that.”

Lynn says many construction companies take advantage of employees through the employer sponsorship track. “Most people abuse that,” he says. “They work them and don’t pay them. They know they have no recourse of action.”

Universal Floors pays workers the going rates, and if the employees move on to other companies or start out on their own, Lynn champions their success. “If they go out on their own, we’ll help them buy their equipment, or they can use our equipment; we help them buy a van,” he says. “We figure the more successful they are, they’ll work with us.”

Generational differences: the trade as a choice

Although Nguyen grew up on job sites helping out his father’s hardwood flooring business, it wasn’t the life his parents wanted for him. It was dusty, physically demanding and viewed by much of his family as “a stupid-people business,” he says. “A reason we’re losing a lot of younger folks, especially immigrants, in the industry is because, as with me, their parents just ingrain to them that schooling is the way to go,” Nguyen says, adding that people who’ve just arrived in the U.S. often don’t understand the debt that higher education can entail. “They just see all these beautiful ‘American dream’ depictions that the movies draw,” says Nguyen. His parents pushed him toward academia and, for a while, he followed, despite an overarching feeling that it wasn’t right for him. “I kept lying to myself,” he says. Eventually, he got his GED and began looking into certifications he could earn at nearby colleges. It was while working at a pharmacy that he asked his older brother to take him on at his flooring business. “The scholar route is a path that the government and the system has drawn out for you,” says Nguyen. “Whereas in the contractor’s life, you can make your own path, and the beauty in that is that you can go as far as you’re willing to work.”

Daniel Rios Carrasco found a similar freedom and connection in the hardwood flooring trade when he moved to Denver from Torreón, Mexico. “I like to do things with my hands and build things with my hands,” he says. When he founded Walnut Hardwood LLC two years after moving to the U.S., it was the perfect combination of craftsmanship and independence. “I don’t like to work for other people, and I don’t like having people tell me what to do,” he laughs. “I have had this problem since I was young.”

Daniel Rios Carrasco learned hardwood flooring, business and English simultaneously.

Daniel Rios Carrasco learned hardwood flooring, business and English simultaneously.

As a young, numerically minded pro, Hakob Karapetyan’s biggest advice to young immigrants starting out in the industry is to fail often—a concept he notes previous generations have been especially fearful of. “The earlier you fail in your early ages, the longer the time span you have to recover,” he says. “We learned the empirical way. We failed and failed and failed and came to realize that out of the failure, you take something valuable that no course can teach you.”

For second-generation pros like Jonny Capalnas, joining the industry was also a matter of continuing on and improving upon a legacy. Capalnas’s father spoke little English when he arrived in the U.S. from Romania, but he built his business on what he called “the universal language,” Jonny says, “which is one of kindness and integrity; taking care of your people, taking care of your customers.” Seeing first-hand how hard his father worked to evolve a small business into a revered distribution empire inspired Jonny to jump into the industry, as well—something he says is becoming less common with other family hardwood flooring businesses his company works with. “Having seen my father, who had less opportunities than I’ve had, obviously it motivates me to continue to carry the baton, to continue with the same principles that the company was founded on,” Jonny says. “Those principles aren’t going to change. If anything, I’ll strive to do those things better.”

In Nguyen’s case, growing up working with his father on job sites more often than not made him embarrassed. “His work was sloppy, and his mentality in the job was: Get it done, get the money and get out,” Nguyen says. It’s understandable: Nguyen’s father took on the trade not because it was a passion, but because it was what he had to do to survive and support a family in a new country. But for Nguyen, the trade was a choice. And, thanks to new technology and social media unavailable when Nguyen’s father began, it’s a craft with seemingly ever-expanding opportunities. “There are so many other ways to do this where you’re not coming home aching,” says Nguyen, who recently invested in the first planetary sander for his company, which he founded shortly after the start of the pandemic.

Now, Nguyen’s building on his new career choice, and he’s bringing a newfound passion to the industry with him. “It was the best decision that I’ve ever made,” he says. “And there’s so much more stuff to learn.”

Jon Capalnas, left, built a distribution empire after emigrating from Romania. His son, Jonny, right, is carrying on the legacy.

Jon Capalnas, left, built a distribution empire after emigrating from Romania. His son, Jonny, right, is carrying on the legacy.

The hard work pays off

Tony Martin was watching the Suns game when his wife, Gina, came over. She asked him how he felt seeing his floor on TV. Martin reflected. He should be jumping for joy, he thought. But he wasn’t. The Suns court project was an accumulation of decades of hard work that began when he set foot in Phoenix for the first time and noticed the lack of tumbleweeds; it was the result of a quiet hope that began to grow when he began doing the gym floors for schools and universities across the state. And it was also, simply, another day’s work. How do you react when a once seemingly impossible dream comes true and then looks back at you through the screen? “I am happy, but I don’t want to feel like I ‘made it,’” says Martin. “I guess I’m just humbled at the opportunity. And I want to keep it that way.”