Luis Perez’s dream is to complete a gym floor in each one of the 50 U.S. states. If that sounds far-fetched, you should know he’s already completed one in 27 states—and he’s only 31 years old.

In an industry that is rapidly aging, Perez, who owns and operates the acclaimed Hero Flooring in Cincinnati, represents a unique group of wood flooring contractors, one that is highly motivated, highly successful in the craft and well under the age of 50. And in an industry that has also historically been made up of predominantly white men, Perez is Black. “There’s not a lot of Black guys who do this,” Perez says. “A lot of times when I tell people what I do, they’re just like, ‘Holy crap—I didn’t even know that job existed.’” Young Black men and women are a demographic with a huge amount of untapped talent, skill and potential for the wood flooring industry, Perez notes. So, particularly at a time when the craft is in dire need of a new generation of craftsmen to pass the handle of the big machine over to, why is a career in hardwood not more of an option for young men and women in the Black community? And how can it become a better, more available option? “It’s something that I feel like we need to shine more light on,” Perez says.

WFB spoke with Black wood flooring pros from across the U.S. and beyond to share their thoughts, experiences and advice for building and uplifting the next generation of Black hardwood flooring pros.

The Jones family, including Jeff Jones and his sons Justin and Jacob, are continuing a family legacy of Black wood floor pros that dates back to the 1920s.Monica Dyrud

The Jones family, including Jeff Jones and his sons Justin and Jacob, are continuing a family legacy of Black wood floor pros that dates back to the 1920s.Monica Dyrud

Low percentages in the industry

The percentage of Black and African American people working under the Department of Labor category of “carpet, floor, and tile installers and finishers” has fluctuated over the past five years, hitting its highest point in 2018 when the demographic made up 8.4% of installers and finishers. In 2021, the latest data available at the time of this publication, Black and African American workers made up just 6.2% of a flooring trade that was otherwise 88.8% white. It’s just over a point more compared with 2003, when Black and African American workers made up 5.1% of the trade.

Representation Matters

Ernest Sisson recalls sanding his first floor as a teenager with a friend for the friend’s mother in the late 1990s. “We screwed the floor up while his mom was on vacation,” Sisson laughs. “We took at it with palm sanders.” They eventually rented a drum sander to attempt to mend the mistakes. “The floor didn’t come out perfect, but it was not horrible,” Sisson recalls.

After Sisson’s first foray into the trade, he didn’t pursue it as a full-time profession right away. Instead, he worked for nine years in sales at Comcast, which he credits for honing his customer service skills. During that time, Sisson became a sought-after “weekend warrior,” doing wood floors for friends and family and gathering clientele from referrals. At the age of 36, in 2016, he made the leap to launch Sisson Hardwood Flooring in Detroit. Since then, the business hasn’t had a busy season—because every season is busy.

Motivated by the artistic aspect of the craft, Ernest Sisson launched his business in 2016.

Motivated by the artistic aspect of the craft, Ernest Sisson launched his business in 2016.

Now 41, Sisson says it makes him proud to have started something from nothing and watch it grow. “Never in a million years did I think that we would be as busy as we are,” he says.

In Detroit, a city with a large Black population, Sisson regularly sees people renting machines at Home Depot for personal jobs, but rarely do local Black men and women take it to a professional level. He believes representation in the industry may play a part in that.

“I honestly think if there were more representatives from different companies that could go into the different neighborhoods, it would be encouraging,” Sisson says. “To see someone that looks like you that’s successful—I think that would drive other young men and women to actually have hope or desire to do something with the hardwood floor industry.”

Sisson didn’t have that person to look up to when he started out in the industry. “I just believed in myself,” he says. “I looked at floors as an art. And learning the different species of wood was interesting to me, as was seeing how different finishes look on different kinds of wood. Those types of things pushed me to keep going and learning as much as possible.”

If more young Black men and women had that representative to look up to, he says, “the sky’s the limit to helping people boost their career or start their career.”

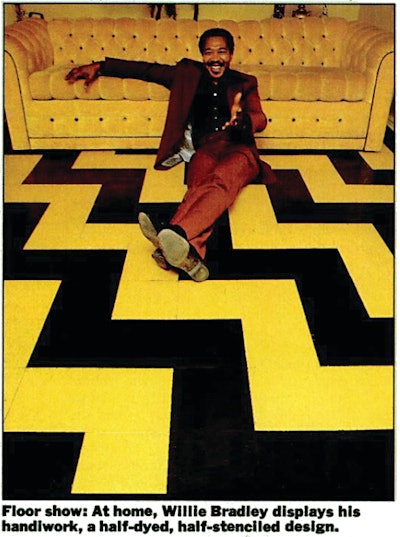

Willie Bradley

Part I

Willie Bradley, 79, of NYC-based Bradley Flooring became known in the 1960s and 70s as the “man who did Jackie Onassis’ floors.” He helped pioneer stencils, dyes and checkerboard designs in chic Manhattan apartments, and he can match a stain in 15 minutes just by looking at it. He became something of a legend for staining a high-profile client’s floors ebony at night without getting a single drop on the baseboard. He trained generations of wood flooring pros without hesitating to kick them off of jobs if they were late or careless.

He achieved all of this despite the myriad roadblocks he encountered due to race. “It was so hard for me as a Black man to get inside these jobs,” he says.

Raised in New Orleans, Bradley was in middle school when a white friend showed him that the textbooks Bradley had been given were beneath his grade level. “I was in the eighth grade and he was in the sixth, but I had never seen that book before,” Bradley says. “I decided then that I had to learn everything I could learn anywhere I could.”

He quit school at 17 to help his family, and worked delivering milk for $10 a week. From there he got a job loading trucks for Pepsi-Cola. Along with helping out his family financially, Bradley ensured the home had plenty of milk and soda. “I worked my way up the ladder,” he says. (continued below)

The potential of outreach

Queral Butler, director of projects for Washington D.C.-based Classic Floor Designs, sees more outreach in the Black community as a potential way of encouraging more Black professionals to enter the trade. “A lot of people just don’t know about the nature of the work,” Butler says. “They see the installers—that’s hard labor; they don’t see all the benefits. They don’t see the National Wood Flooring Association, they don’t see all the shows that we go to and all the people we meet. You have to have a passion for flooring, a passion for wood, a passion for craftsmanship to thrive in this work.”

Butler himself found that passion at the age of 15 working with his older brother, Mike, for a flooring company in his native West Virginia. “First, I loved the demolition,” he laughs. “I got to go in and actually start tearing things apart, which I had never been involved in before in a home.”

Queral Butler handles high-end flooring projects for Classic Floor Designs.

Queral Butler handles high-end flooring projects for Classic Floor Designs.

Seeing a new wood floor then get installed and watching the entire space transform before his eyes sealed the deal for Butler. “It was invigorating to me,” he says.

He went into business with Mike at the age of 19 before eventually branching out on his own and doing subcontracting work for about 10 years. He was thinking of going in a different direction when he was offered a managerial position in 2013 with Classic Floor Designs, a company he’d built a relationship with over the years and where he’s since helped cement it as a staple in the high-end hardwood flooring industry.

As much as he loves the craft itself, Butler’s favorite part of his job has always been “when you’re with the guys and you’re laughing through the pain,” Butler says. “That’s something you never forget. The guys that used to work with me years ago, when we get together and see each other, we still talk about old times and laugh. Even with the crews now, we try to keep humor through the pain.”

Getting the business off the ground

In the tight-knit community of Southampton , Bermuda, the Taylor name is synonymous with wood flooring. That’s no accident. The Taylor family has been sanding and finishing flooring there for four generations.

Coming from a family flooring business, the Taylors recognize the challenge of launching a new company, particularly for those in the Black community. “Financially, it’s hard to come out of the blocks as a Black man,” says Damon Taylor, 47, a third-generation pro whose grandfather started the Taylor’d Flooring Ltd. dynasty. Damon took the business to new heights, adding its installation component. “To get started in the wood flooring business, it’s very expensive. It may be a matter of a lack of resources and not having backing for it; people go through hard times, and maybe their credit is not good.”

There is a disparity in credit scores among the Black population in the U.S. According to the latest available data from the Federal Reserve, the Black population has the lowest average credit score, at 677, compared with 701 among Hispanic whites, 734 among non-Hispanic whites and 745 among Asians. Data released by the Federal Reserve in 2020 subsequently found that more than half of Black-owned businesses are turned down for loans, a rate that is twice as high as white-owned businesses that apply for loans. Less than 47% of loan applications by Black-owned businesses are fully funded.

That disparity can make it hard to get started. In Bermuda, Damon explains, a $7,500 sanding machine quickly turns into a $10,000 investment with shipping and duty fees. “That’s why guys have a hard time starting their businesses, because just to get off the ground is almost impossible,” Damon says.

Damon Taylor II, 18, pictured far right, is the latest addition to the Taylor family flooring dynasty in Bermuda.

Damon Taylor II, 18, pictured far right, is the latest addition to the Taylor family flooring dynasty in Bermuda.

For Damon’s father, Lionel Taylor, 74, maintaining something lasting that he could hand over to his children was important to him as a Black craftsman. “You need a type of business that can carry on what it’s doing,” Lionel says. “That’s why Damon can do that, because I have a good business that can be turned over. He’s got nothing to worry about. But you’ve got guys out there that sand floors for $3 a foot. We’re out of that racket.”

Courtney Lee of Lawrenceville, Ga.-based Truman’s Hardwood Floor Cleaning and Refinishing ran a highly successful carpet cleaning business before venturing into hardwood floor cleaning, maintenance and recoating full-time at the end of 2020. He quickly became known for his screen-and-recoats and his personable approach with clients, a trait that has also helped him amass over 23,000 subscribers on his YouTube channel. “I think Black people have always been in the cleaning industry; we’ve always been those types of individuals that did labor-intensive work and cleaning,” Lee says. “But when it comes to having less of a presence in hardwood floors, I think a lot of it is lack of knowledge and a lack of financing.”

Lee notes that there’s a reason carpet cleaning services like Stanley Steemer can maintain large fleets with numerous locations and franchises—compared with hardwood flooring, the financial risks are lower. “To me, hardwood flooring is more about craftsmanship; it takes a certain individual,” Lee says. “And one thing I’ve noticed with hardwood floors, whether it’s sanding or maintenance, is: If you mess up a floor, it can cost you a lot of money.”

Lee has seen instances where someone will take on a new job, mess up the floor and end up having to pay thousands to have it fixed or replaced; after that, the individual will hang up the scraper for good. “Not everyone has $10,000 in the bank,” Lee says.

II

The next rung of the ladder for Bradley led to a job mixing terrazzo flooring, which required loading hundreds of bags of cement every morning in the thick New Orleans heat. Despite the intense labor involved, Bradley developed a knack and a fascination for pouring and mixing the colors in the flooring, and soon he was training others to do the same. But any amount of potential the job might have had was snuffed out as the white men Bradley trained were continually promoted over him. When Bradley refused to train anyone anymore, he was dismissed. Barely 18, Bradley headed to New York, where his brother was driving a truck for a wood flooring company. (continued)

Facing social pressures

Izaiah Barrow, 32, grew up in the trade, learning the craft from his uncle and grand-uncle in New York City from the time he was 11 years old. He launched his own company, iSandNewYork, in 2016. Aside from his uncle and grand-uncle, Kyle Kirkland and Willie Bradley, respectively, Barrow says he’d never noticed many other Black men or women doing wood floors. In a way, Barrow says being Black helped him to stand out when he started his business. “I was one of one, basically,” he says. “I don’t look at it as a bad thing, I look at it as though it leaves more opportunity for me to motivate some of these brown and Black kids in my community to get on these sanding machines and start these businesses.”

Three generations of NYC-based floor pros (left to right): Willie Bradley (grand-uncle), Kyle Kirkland (uncle) and Izaiah Barrow (nephew).

Three generations of NYC-based floor pros (left to right): Willie Bradley (grand-uncle), Kyle Kirkland (uncle) and Izaiah Barrow (nephew).

Barrow says he’s felt appreciated for his work and craftsmanship since he launched his business, and he knows he’s discovered the career he’s meant for. But along with standing out in the trade, being young, Black and from the Bronx comes with societal pressures that can bleed into the wood floor business.

“People doubt you, people don’t think you’re worth a certain type of money,” he says. “People don’t believe in your artwork, people don’t believe in your craft. So here it is: I’m a third generation floor man, my family’s been in business for almost 70 years, and we’re still trying to prove ourselves.”

“It’s just the normal pressures of America for a Black man,” Barrow continues. “But that’s what makes you strong, that’s what makes you an American Black man.”

To stick it out and succeed in the wood flooring industry takes a willingness to work hard and focus, Barrow notes: “And as Black folks, we have that.”

III

Bradley got a job doing wood floors in New York City, but he wasn’t a welcome presence on the job sites at first. “There were no Black mechanics doing floors,” he says. “The guys, when they didn’t want me to learn something, they would send me to the store.” Fortunately, Bradley was a fast runner—he made it his mission to return from errands as fast as he could to soak up the trade. He’d also make a point of showing up early to complete his tasks before his coworkers arrived. “That way I could watch them and learn,” he says. “I would get there really early in the morning, finish my work and see how to sharpen those tools.” His fellow tradesmen at the time were mostly white European immigrants, and he looked for ways to get into their good graces to get them to show him the craft. “They always wanted to go drink,” Bradley laughs. “I’d go buy them drinks and listen to them tell me stories about floors.” (continued)

Breaking the trade’s racial barriers

John C. Wilson, 64, of Atlanta-based Wilson Wood Flooring Co. remembers being sat down by the superintendent of a construction company overseeing one of the biggest jobs in the city in the 1980s. The superintendent explained that he’d “never seen a Black guy that owns a company in the flooring business.”

“This is a major project that we’re taking on and we’re a little concerned about giving you this job,” the superintendent said. Wilson looked at the superintendent and replied, “You give us this job, and we’ll show you that we’re not nervous.”

Wilson got the job. He came in three weeks under schedule. They contracted him four more times after that.

Wilson didn’t stop at showing the superintendent what he was capable of—he showed the entire city of Atlanta and beyond, becoming a household name and building a wood flooring empire that now spans Washington D.C., Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina and Georgia, while training dozens of wood flooring professionals who went on to found their own companies around the U.S. and even Africa. His company has operated as referral-only for the past 35 years.

John C. Wilson has made Wilson Wood Flooring Co. a household name in Atlanta since launching in 1979.

John C. Wilson has made Wilson Wood Flooring Co. a household name in Atlanta since launching in 1979.

Wilson started his company in 1979, refinishing floors for professors at Morehouse College, where he was attending on a tennis scholarship. Wilson had an uncle in the industry and had previously helped his high school gym coach refinish the gym floors at his high school every year. His professors kept referring him to other clients, and before he knew it, Wilson had a bustling business, working for upper-middle class Black clientele in the Atlanta market. He remembers being told by another floor pro early on that the Black communities were underserved, “because there’s just not really enough Black contractors to go around.”

Before long, Wilson expanded into other markets. It wasn’t easy. “There have been contracts that I sure should have had but they just felt that we weren’t capable of handling it,” he says. He also remembers pulling up to work on a home in the late 1980s and being met with a double-barrel shotgun and a demand that he get off the property.

It took skill and dedication to break through barriers in other markets, but break through Wilson did: His craftsmanship became a fixture in numerous country clubs, the Ritz-Carlton and the Bank of America Plaza. He credits his drive in part to his entrepreneurial upbringing in South Carolina, where everyone in his family owned a business (Wilson launched his first business at the age of 12, selling wood from his parents’ property).

“I think it’s all about how you present yourself; you’ve got to be able to communicate with all sorts of people everywhere,” Wilson says. “The way I grew up, we were taught to fear nobody and no situation … Being able to communicate, you have to break down barriers. One of the things I’ve found out is that your reputation will break down a lot of barriers.”

Dealing with client prejudice

Being 6 foot 2 inches tall, 204 pounds and Black, Kyle Kirkland, 59, of New Rochelle, N.Y.-based Kirkland Flooring says he had to develop a skill for getting people to let their guard down when he’d arrive on-site. “On day one of a job, people would react like, ‘Whoa,’” Kirkland says. “Day two, they’d be polite; day three, it was like we were family. It happened quite a bit.”

Kirkland moved from Chicago to New York City at 19 to work with his uncle, Willie Bradley of Bradley Flooring. Bradley fired him. But Kirkland returned two years later. “When I started, I was just looking for a paycheck,” Kirkland recalls. “When I returned, I was ready for the work.”

Kirkland dedicated himself to the craft and quickly rose through the ranks, taking on challenging, high-end floors. “I like the most difficult projects, especially when it comes to colors, mixing colors for decorators and getting creative,” Kirkland says. “I was doing a lot of herringbone, French parquet—things that a lot of guys back then were afraid of.”

Kirkland started his own company when he was 34 but has continued to work closely with his uncle over the past 40 years. During that time, he experienced multiple instances where he was made to feel uncomfortable on job sites, and where he felt some clients attempted to see how far they could push him with menial tasks. His solution was to always respond by continuing to do the best job he could. “I’m just that type of person,” he says. But Kirkland feels conditions are improving for the next generation of Black wood floor professionals. “I’m happy they don’t have to deal with what we had to deal with,” he says.

Kirkland has nothing to prove these days. He learned recently that two New York City billionaires were having lunch and arguing over who had the best flooring contractor. In the end, it turned out they were arguing over the same craftsman—both were his clients.

Courtney Lee is using his YouTube presence to promote Black wood floor craftsmen.

Courtney Lee is using his YouTube presence to promote Black wood floor craftsmen.

IV

With a fierce determination to learn, Bradley gradually got a handle on the trade and the machines. On early projects, he was often instructed to use the back doors while his white counterparts went through the front. Bradley started dressing as nicely as he could to get in the doors. “I went to a lady’s apartment one time,” Bradley recalls, “and she looked me up and down and said, ‘Sir, you are the most fancy-dressing floorman I’ve ever seen.’”

In his early 20s, as he was beginning to excel in the craft, Bradley quit after his boss’s attempt at a Christmas bonus offended him. “All he gave me was a cheap bottle of whiskey,” Bradley says. “I didn’t drink that stuff. It was cheap. So, I left.” Bradley went to work in Detroit plastering for a time. When he returned to New York City at the age of 23, he launched his own flooring company. Looking back 60-odd years later, that cheap whiskey may have been one of the most profitable gifts Bradley was ever given. (continued)

How ‘The 6-Pack’ helped open industry doors

When John Wilson attended a wood flooring convention in Orlando in the early 1990s, he was reminded of playing tennis in his youth—when he would be the only Black person in attendance. “Being Black and in this business is very rare,” Wilson says. But as the convention went on, “I started seeing other Blacks coming into the building—and, eventually, there were six of us.” The six craftsmen quickly bonded over their shared experiences in the trade. And 30 years later, that group, who dubbed themselves the “The 6-Pack,” is still going strong. “It’s a brotherhood that was formed from this, and we stay in touch still to this day,” Wilson says. The group consists of impeccable craftsmen from all backgrounds and regions and includes Louis Johnson from Minnesota; Randy Stafford from Bermuda; Benjamin McAdoo from California; Troy Smith Jr. from Virginia; Julius Askew from South Carolina; and Wilson.

“All these guys are very talented and very smart, and they’re great businessmen,” Wilson says. “It meant the world to be able to find that group, and they all come with great integrity about who they are.”

Wilson believes the industry has changed since that fateful trade show when he met his fellow 6-Pack colleagues—it’s opening up. “I think after interacting with the 6-Pack over the years, the whole association has opened up more to be more receptive to more minorities,” Wilson says. Wilson noticed more young Black wood floor pros attending the 2022 convention in Tampa, and with them a shift in attitudes. “I look at the reception that the young new group got; there were open arms, everybody wanted to help, everybody wanted to show their support,” he says. “And that meant a lot.”

He hopes the careers and legacy of the pioneering members of the 6-Pack has helped open more doors for the next generation of Black talent in the industry.

“I think we as the 6-Pack have to become mentors,” Wilson says. “If the younger generation wants to venture into this arena, we can show them what we know, and teach them that it’s not the easiest work to do—but it’s very rewarding.”

V

After his business launched, Bradley got a job washing cars in the garage of an apartment complex at night. In the morning, he’d pass out his hardwood flooring business cards. He struck a deal with the building’s superintendent: recommend Bradley’s flooring company to tenants, and if Bradley landed a job, the super would get 20% of the profits. The partnership didn’t last too long, as recommendations for Bradley’s work began to spread from the tenants themselves and to other buildings. Bradley remembers 135 Central Park West in particular. “My name went up and down that building like wildfire,” he says, “and from there it just took off.” (continued)

Discovering the rewards

Luis Perez started working in the trade at the age of 19. But it wasn’t until around 24 that a vision for crafting boundary-pushing gymnasium floors began to take shape. By then, he had the fundamental skills under his belt. “Once it became second-nature to me and the floors were no longer a challenge, it became a matter of, ‘Alright, how do I make this fun?’ And that’s where the artwork came in,” Perez says.

Even if his ambitious a-gym-in-all-50-states goal does not pan out (which, at the rate Perez is going, seems like a losing bet), Perez knows he already holds a sanding-machine-shaped key to his future. “I could drop everything I have right now and go get a residential job in any city somewhere for $25 an hour if I really have to,” he says. “Once you learn those skills, nobody can take that from you.”

At age 31, Luis Perez is raising the bar for artistic gym floors.

At age 31, Luis Perez is raising the bar for artistic gym floors.

He relied on those skills repeatedly when doors were closed in his face as he built his reputation and gym floor business: “The only thing that’s always really had my back has been the floor.”

The security of knowing the skills of the trade is as certain as never knowing quite where the trade will take you. “You’re not at the same job every day,” says Kyle Kirkland. “You’re meeting new people, and you’re making artwork.”

Retired wood floor pro Jeff Jones, 65, who founded Pasadena, Calf.-based Sunwest Hardwood Floors in 1980, remembers the thrill of doing wood floors for celebrities with his uncle in his youth in California. “Every day was an exciting day, because we didn’t know where we were going to go and who we were going to see,” he says. He went on to work on wood flooring projects from up and down the California coast, racking up floors and unforgettable experiences (including that time client Alice Cooper made him a sandwich and then invited him to play basketball). “This job can take you places,” Jones says.

Ernest Sisson grew up in an artistic family and is also an in-demand professional photographer. The creative fulfillment of doing wood floors is his favorite part of the craft. “I’m a big fan of staining floors, doing custom stains and making colors,” he says. “A lot of guys don’t want to mix stains to create a color to match others, but I get my biggest excitement out of staining and just seeing the client’s face when everything is completed.”

And as with many other wood floor pros, for Perez, the ability to do the work for himself and follow his own path continues to be a huge motivator for him.

“I take pride in being able to feed myself and my family—nobody tells me when to get up to go to work anymore,” he says. “I don’t clock in for someone else; I clock in for myself.”

VI

He stayed below 96nd street, “where the money was,” connecting with interior decorators along the way and gradually amassing a high-end clientele. Perhaps his most fateful connection was with Bill Erbe of William J. Erbe Company, a wood flooring master who did wood flooring for the White House and palaces in Kuwait. Bradley beat Erbe in a bowling tournament, and a lifelong friendship was formed. Erbe recommended Bradley to some of his past high-end clients, including Jackie Onassis, who could afford Erbe’s services only when she was in the White House, Bradley says. Bradley eventually became well known locally as “the man who did Jackie Onassis’ floors.” Erbe was also responsible for getting Bradley to raise his prices. Bradley had been charging $1.50 a foot, compared with Erbe’s $15 a foot. He remembers Erbe telling him, “‘Charge a lot of money, because then if you’re as good as me and still charging nothing, why should people use me?’” Bradley followed the advice and never looked back. (continued)

The Jones brothers continue a family legacy

It’s something of a tradition in the Jones family to be used as a buffer weight when you’re growing up. It happened with Jeff Jones, 65, and so it was with both his sons, Justin, 33, and Jacob, 32. The third- and fourth-generation pros inherited their wood flooring passion from John L. Jones, Jeff’s grandfather, a pioneering wood flooring craftsman who in the 1920s launched Jones Housecleaning and Floor Service in Pasadena, Calif., and trained numerous Black wood flooring professionals. Many of their descendants can still be found in the business throughout California and beyond.

Jeff learned the craft side of the business from his uncle and launched his own business, Sunwest Hardwood Floors, in 1980. He found his niche doing wood floors for celebrities like Buddy Hackett and Diana Ross. “I used to go to bed thinking about floors, get up at 4 a.m. to go work on wood floors, and not stop until 10 p.m.,” says Jeff, who recently retired.

Jeff Jones (left) and sons Jacob and Justin carry on a family legacy of wood flooring that goes back to the 1920s.

Jeff Jones (left) and sons Jacob and Justin carry on a family legacy of wood flooring that goes back to the 1920s.

It was quite the hardwood flooring legacy to live up to, and for a long period, Justin and Jacob didn’t see themselves joining the trade. Justin initially worked in food service. “I’m the oldest in my family, and my parents really wanted me to go to college,” Justin says. “I tried, I just wasn’t very studious.”

Jacob became the first family member to complete college, earning a degree in environmental business. But when Justin and Jacob were in their mid-20s, both made a decision to try the family wood flooring business full-time, just as their father was beginning to wind it down. “My dad was like, ‘I worked too hard for my money, I don’t want you to have to go through that,’” Jacob recalls. “As much as I appreciate that, I kind of like working hard.”

There was some pressure taking up the torch, of course, but it also pushed them to take risks that made them better in their craft. “As a young guy trying to maintain that standard without necessarily the experience, you kind of do have to push yourself to do things you’re not sure you can,” Jacob says. “And so you jump in with both feet and hope for the best.”

John L. Jones, far left, arrived in Pasadena, Calif., in 1925 by way of Arkansas and Washington.

John L. Jones, far left, arrived in Pasadena, Calif., in 1925 by way of Arkansas and Washington.

Sunwest Hardwood Floors is going strong and continues to be a fixture in Pasadena, maintaining the area’s plethora of historic floors as their great-grandfather did before them.

“We’re multi-generational, we are Black, have Black heritage, but we’re also locals to our community, and I think that’s important,” Justin says. “I would say that just for the young people and for minorities, get out there and try to tap into the industry. A lot of people don’t know it’s possible—like me when I was a student, trying to go to college and not realizing that what I had in front of me had a lot of value.”

VII

In 1979, Bradley was profiled by New York Magazine and pictured with his own home’s “bachelor-pad” wood flooring, featuring a checkerboard-inspired pattern, stenciled and dyed with a contrasting deep black and bright yellow at a time when such custom color work was rare. After the article ran, Bradley received a huge wave of demand for the design, although the clients typically requested colors with a somewhat “softer touch” than Bradley’s black and yellow. (continued)

A drive to give back

The presence of successful Black wood floor professionals has not only helped inspire other Black individuals to enter into the trade—it has also helped uplift entire Black communities, as pros make a point of using their businesses to give back.

Izaiah Barrow of NYC-based iSandNewYork used his platform as a flooring pro to launch “We Are Theory 9,” a non-profit to help teach kids basic life skills. “My whole life I’ve been working in million-dollar homes and mansions, and at the end of the day I go back to my little humble abode in Kingsbridge [in the Bronx],” Barrow says. “And Kingsbridge isn’t a bad area—it’s a beautiful community. But it isn’t New Canaan, Conn., it isn’t 66 Leonard Street, N.Y. So, when I would wake up in the morning and work with these clients and see how they live and come back home, it wasn’t a sense of jealousy, it was a sense of, ‘I’ve got to bring my people up.’”

Barrow’s organization also does backpack giveaways, turkey drives and Christmas toy drives. “I just want to see my people have a little something more, something they didn’t know was out there,” Barrow says. “Because some of us don’t know what’s out there; we’re stuck within our four or five-block radius—and thank God wood flooring has allowed me to see way farther past my nose.”

For John Wilson, the proudest moments in his 43 years in the trade have been when he’s been able to give back to his community—whether through charities like 100 Black Men of America or Ronald McDonald House Charities—or by simply surprising a client with a high-end floor project. “Some of my proudest moments are our charity work for clients who know they have a big price tag ahead of them, and when they get the bill, they find out that it’s zero,” Wilson says. “I like to focus on individuals, especially for people who really can’t afford my services.”

Wilson also aims to provide opportunities for young Black individuals to work for him. He’s hoping to find a way to create more wood flooring programs for inner-city youth. “I would like to see more opportunities for Blacks in the industry,” he says. “It makes a big difference. I had one kid that worked for me, and I knew that he was in the streets when I hired him. I told him, ‘I know you’ve got babies out there in the streets; if you come to work for me, you’ve got to be a responsible father. If you take care of your children, I will take care of you with this business.’ That was 27 years ago, and he’s still with me and has learned a lot since then. He came to me one day, and he said, ‘If it had not been for you and this business, I would be dead like all of my friends.’”

Wilson says the wood flooring industry has a lot to offer, and if there were more helping hands along the way, a lot of lives could be improved, or even saved.

“We can create a lot more flooring contractors in this country, because there’s a lot of wasted talent that’s out there in the streets that would never be able to do anything because they’ve never been given an opportunity,” Wilson says. “And hardwood flooring is a great opportunity. It won’t judge you based on where you come from or what you did in the past—it’s about what you’re willing to do, and will you do it.”

VIII

Bradley continued to work for high-profile jobs and clients throughout New York City and beyond over the decades, running a tight ship with his business that demanded excellence, all the while continuing to learn from anywhere he could. “You make your own pot of soup,” he says. “Learn a little bit from everyone.” When a tricky color needed matching, it was Bradley’s phone that would ring. “If you look at any color long enough, you see more than just one color, especially a deep color,” he says. Although he’d achieved great success in the trade, his business never quite grew to the extent he’d envisioned; unlike many of his competitors, he never amassed large fleets of vehicles that could traverse the city and bring brand recognition. “I wanted this company to be so great, that whenever you went anywhere and told them you were from Bradley’s Floors, you could get a job anywhere,” he says. “It never did grow to that.”

But Bradley, mostly retired but still doing specialty projects around the country, has faith that the next generation of wood flooring professionals will do the trade justice—and continue to learn. “I’m proud that I got some people to see the light and what I was trying to teach them, and trying to instill within them the value of their merchandise,” he says.

Willie Bradley is mostly retired but still doing specialty projects around the country.

Willie Bradley is mostly retired but still doing specialty projects around the country.

Those who came before

Luis Perez recently reconnected with his grandfather and started learning about his family’s history. He learned his great-great grandfather was enslaved. He also learned that his great-grandfather was a builder who contributed to the construction of the Sears Tower (now the Willis Tower), which stood as the tallest building in the world for nearly a quarter of a century. And as for Perez’s grandfather, it turns out he’d spent the last 20 years working as a truck driver, traversing many of the very same roads Perez has traveled while creating masterful gym floors. “That just means a lot, to know your own history and put those pieces together—that’s stuff I never knew was in my DNA,” Perez says. And now, as he continues to pursue his dream of installing his signature floors across the U.S., Perez is carrying with him those who came before. “I think it’s very important for your self identity to know where you come from,” he says. “It gives you a lot more purpose, and gives you a reason for why you are the way you are.”