During the winter, even the most carefully installed wood floors tend to dry out and shrink. Customers begin to notice gaps between boards, and the phone calls begin. The floor behaves that way because of wood's relationship with moisture in the air (there's no accounting for how the customers behave, although educating them about gaps beforehand can help—more on that later). Air with a low moisture content, or low relative humidity (RH), causes wood to lose moisture. When wood loses moisture, it shrinks. What can we do about it?

To control winter-related shrinkage of flooring and the consequent gaps (what we used to call "cracks"), we have basically six options. Four deal with the wood itself, and two deal with moisture. Let's get the wood ones out of the way and then discuss moisture issues.

Wood Options: Use the Right Flooring

Engineered flooring is supposed to be more stable than solid wood. From a technical aspect, this should be true. But many engineered flooring manufacturers restrict the use of their products to a certain RH range. I've seen warranties that specify 35 to 55 percent RH or 40 to 60 percent RH as the acceptable range. If the flooring is exposed to conditions outside these ranges, the warranties are void. In my 30-plus years of experience dealing with indoor environments in the U.S., I don't know any location that will consistently maintain those RH ranges. So using engineered flooring may be an option for reducing winter-time floor issues, but check the manufacturer's recommendations and warranty.

Narrow boards will shrink less than wide boards for a given change in moisture content (MC). A 5-inch-wide plank will shrink twice as much as a 2¼-inch-strip. So the size of the gap between 5-inch boards will be twice as big as the gap between 2¼-inch boards. More joints means more places to distribute gapping.

Some species are more dimensionally stable than other species. For a given change in MC, a 5-inch-wide hickory plank will shrink more than a 5-inch-wide red oak plank. The U.S. Forest Service, and others, publishes dimensional change coefficients for different species. A second solution to excessive winter gapping is to use a species of wood that is more stable (one with a smaller dimensional change coefficient).

Along the same line of varying dimensional stability, quartersawn flooring shrinks about half as much as flatsawn flooring for the same amount of moisture change, so quartersawn flooring will have smaller gaps than flatsawn flooring under the same circumstances.

Therefore, from a wood standpoint, to have the smallest winter gaps, use quartersawn, narrow boards from a stable species.

RELATED: Can We Be Proactive in Preventing RH Problems for Wood Floors?

Moisture Issues

The other approach to winter gapping is to address the moisture issues. Gapping and associated noises usually occur when the flooring dries significantly from its summertime high moisture levels. So, to reduce winter gapping, reduce the annual range of moisture levels. Or, more specifically, to reduce winter gapping, don't let the indoor RH drop too much. (Or don't let summer RH levels get too high—but that is another article.) A good annual range for the best flooring performance is a swing of 20 percent RH from wettest to driest. This means that in the Southeast, we may work in a range of 40 to 60 percent RH, while up north they may use 30 to 50 percent, and out west they may use 20 to 40 percent. All will work, as long as the RH range isn't too wide. But sometimes in the winter, the RH tends to dip too low.

There are two approaches to keeping winter indoor RH elevated.

Moisture Option 1: Reduce Ventilation

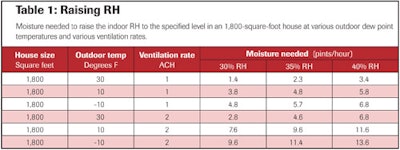

Ventilation of a house is measured in air changes per hour (ACH). As an example, a house that is 1,800 square feet with 8-foot ceilings has a volume of 14,400 cubic feet (1,800 x 8 = 14,400). Changing all the air in this house with fresh air once an hour would be one ACH.

Current building codes and standards recommend home ventilation rates near 1/3 ACH. Not all states enforce these codes or standards. Average homes have ventilation rates near 1 to 2 ACH, while some old, leaky homes are near 7 to 10 ACH. Weatherization and home energy audits typically measure ventilation rates. These programs can also pinpoint leakage sites and direct sealing efforts to reduce excessive ventilation rates. Old windows are often major leakage sites, as are recessed lights and other holes in ceilings and floors.

Moisture Option 2: Add Moisture

As you can see from Table 1, colder outside air requires more moisture. Higher ventilation rates require more moisture, and higher target indoor RH levels require more moisture. Since the ventilation rate and moisture needed are related, an economical approach is to reduce ventilation rates, then add moisture.

RELATED: How Inside Air Affects Wood Floors

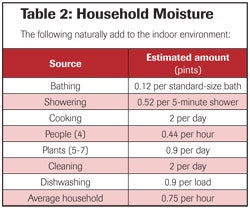

Moisture is added to indoor environments from normal household activities and use. When this moisture is not sufficient to meet the needs, a humidifier can be added. Table 2 shows some typical indoor moisture sources and amounts.

According to Table 2, a family of four contributes about ¾ pint of moisture per hour. This number is likely smaller than that shown, because people aren't home all day and don't clean every day. So I would suggest ignoring household sources when determining moisture needs.

Adding moisture then boils down to using humidifiers. Humidifiers can either be stand-alone or attached to a central forced air furnace. Typical residential systems can provide up to about 6 pints per hour. This is an important number: 6 pints per hour, maximum. Table 1 shows that more than 6 pints per hour are necessary to get to 40 percent RH when it is real cold outside in a relatively tight, 1,800-square-foot house. We can't even get to 30 percent RH in a somewhat leaky house when it's moderately cold outside, or in a larger, moderately tight house. (By moderately cold, I mean the kind of weather I have in South Carolina. By real cold, I mean the type of weather in Minnesota or New Hampshire.)

To make matters worse, moisture output from some humidifiers depends on furnace air temperature. According to Aprilaire, a large manufacturer of whole-house humidifiers, their humidifiers produce a maximum of about 3.6 pints per hour when connected to a heat pump. With that number, we can't even get to 30 percent RH in a moderately tight, moderately sized house in a moderate climate.

Adding Too Much Moisture

Let's say we can get the humidity up in the winter. Now we need to worry about hurting the building and causing condensation or, even worse, mold. Condensation typically forms first on windows. Condensation will form on a typical double-pane window at a RH above 40 percent when the outdoor temperature is zero degrees or below. For single-pane windows, condensation can occur at a RH above 30 percent when outdoor temperatures are below about 30 degrees.

Honeywell, another large manufacturer of humidifiers, recommends an indoor RH no higher than 35 percent when it is 20 degrees outside, 30 percent at 10 degrees, 25 percent at 0 degrees, 20 percent at -10 degrees and 15 percent at -20 degrees. According to Consumer Reports, when the outside temperature drops below 20 degrees, even 30 percent RH may be too high. What all this means is that if we add too much moisture to a house, we can cause condensation and possibly mold on windows. In some cases, walls can rot.

Realistic Solutions

So what do we do? First, we can't fault wood for being wood or doing what wood does. Second, we can't change the laws of physics and make cold, dry air magically wetter but not hurt houses. Therefore, we are left with a few options to prevent large seasonal gaps.

Solution 1: Go back to the basics. Use narrower boards, more stable species of wood, quartersawn boards, or a combination of those features. Or consumers can accept seasonal gaps. This takes consumer education by establishing proper customer expectations. Make sure you explain clearly, and hopefully in writing, that the 7-inch hickory flooring for a house in Chicago will likely have large seasonal gaps.

Solution 2: Use a product that can handle low-RH environments. Solid wood flooring has been used in those environments for years while, based on warranties, much engineered flooring and some factory-finished flooring apparently are not designed for those environments. Pick a flooring material that can handle the normal, local environment.

Solution 3: Change the building design and/or operation. This solution isn't up to flooring professionals. Builders and building owners can take steps to reduce ventilation rates, and/or add humidifiers. Humidifiers do need routine maintenance, as often as every month during the heating season. And we all know how good we are at routine maintenance. So be prepared for some gapping complaints a couple years down the road.

Bottom line: Winter weather dries out wood flooring, causing gaps, possibly increasing squeaks and opening surface cracks. Wood will be wood. Physics will be physics. Inform your clients of these facts, and don't rely on humidifiers or other sources of moisture to prevent normal winter conditions. Humidifiers can help some, as can choosing the right wood flooring for the right situation, but only to a certain extent. If your client wants 7-inch hickory plank flooring with minimal winter gapping, major changes to the house may be necessary. If hairline gaps aren't acceptable, even 1½-inch quartersawn oak strip flooring may not work. Establish proper customer expectations, and everyone wins.

For more information:

To find dimensional change coefficients, go to chapter 13 of the revised Wood Handbook, available for free download.

For more on how wood flooring responds to moisture, read "Under the Microscope: Understand the Science of Water and Wood Floors."

For more from author Craig DeWitt, read:

"The Comfort Zone: How Inside Air Affects Wood Floors," about how the air in buildings affects wood floors, "How to Prevent Cupping and Worse in Summer Months", and many more articles here.

Take a quick quiz on this article: