Not so long ago, many still considered solid flooring the only “real” wood floor. Today, no one can deny the importance of engineered products in today’s wood flooring market, and the products come from every corner of the globe with every species, construction and finish imaginable. No wonder, then, that confusion about engineered wood flooring runs rampant. That’s why we’ve compiled a series of common questions about engineered flooring and asked some industry experts to give us their answers. Remember, opinions vary about the best methodology for the construction of an engineered floor, and not all high-quality engineered flooring is alike. There isn’t always one clear-cut answer to questions like the following. Be sure to do your own homework by asking your distributors and manufacturers to educate you on the products they sell, and make sure the products you choose are right for your region and each specific job.

Do you have more questions about engineered flooring? Send them to WFB, and we’ll include them in a future issue.

QUALITY

How can I tell a good-quality engineered floor from a poor one?

A: There are huge differences in quality in engineered wood flooring, and consumers don’t know how to compare apples to apples—there is more education needed during the sales process for engineered products than for solid flooring.

The first thing is to look at the composition of the flooring: What is it made out of? Is it a low-grade three-ply softwood plywood or a high-quality plywood (such as marine-grade Baltic birch)? Lower-grade plywood has a greater chance for delamination, where the layers come apart. Plywood is designed to perform as a big sheet. When you’re asking it to perform as smaller pieces, such as drawer components or engineered wood flooring, it’s particularly important to use a higher-grade material. Gluing a hardwood piece to the plywood will cause stress on the plywood when the flooring experiences changes in moisture content, increasing the chance for delamination within the plywood, so the plywood quality becomes even more important.

Next you can look at the wear layer. Which type of wear layer is it? (For an explanation of the types of wear layers, see the “Veneer” sidebar below.) Rotary-peeled products are applied to the plywood green; they are initially circular-shaped but are forced flat, and this can later cause face checks. When you’re looking at samples, look at the face of the boards very carefully; with lower quality products, many times you can actually see face checks in the store samples. Those indicate areas of stress release in the face from when the veneer was wet. Also, keep in mind that thin veneers limit the capacity for the floor to be sanded in the future.

Sliced/spliced wear layers are thicker than rotary-peeled but may still have issues with stress release as the veneer dries on the surface. They also have a limited capacity for resanding. Dry-sawn wear layers are available in different thicknesses from 2 up to 5 millimeters (about ¼ inch). They are cut when the board has been kiln-dried and duplicate the look of a solid floor. These products offer the capacity to resand. (That capacity varies with the thickness of the wear layer, of course.)

Many people are extremely concerned about the quality of the finish, but you can’t judge finish by looking at it on a sample. To know how good the finish is, I always tell people to look at the construction of the product itself. If you see low-grade material used as the base, then the finish on top of the floor is probably the same quality. You don’t buy a Mercedes and put the cheapest tires on it, and the same is true with engineered wood flooring and its finish.

Jean L’Italien is training manager at St. Georges, Quebec-based Boa-Franc/Mirage.

MOISTURE

When I am installing an engineered wood floor, I don’t have to worry about moisture, right?

A: The biggest misconception people have about engineered wood flooring is that the products are invincible. Many times the products are sold that way by uneducated sales professionals, and consumers believe it, which leads to inspections and unhappy customers down the road.

When we look at stability as far as cupping or gapping, engineered flooring will outperform solid flooring, meaning you can use a wider-width product without seeing those dimensional changes as much. But that doesn’t mean we can just ignore moisture, especially relative humidity, when it comes to engineered wood flooring. If a solid wood floor experiences very dry conditions, it may show some wide gaps. But if an engineered wood floor experiences dry conditions outside the parameters defined by the manufacturer, the product may delaminate, show face-checking, split and dry-cup—all problems that require board replacement or, if the problems are throughout the floor, total replacement.

When buying an engineered wood floor, it’s critical to read the manufacturers’ instructions regarding the relative humidity necessary to maintain the floor. I’ve seen warranties with relative humidity ranges as wide as 25–75 percent and as narrow as 38–45 percent (a range so narrow it’s almost impossible to maintain). Residential and commercial properties that are maintained outside those ranges for a consistent period of time will void that floor’s warranty. Of course, the quality of the product has a big role in how well an engineered wood floor will tolerate moisture swings, and there is a huge spectrum of quality in today’s engineered wood flooring market.

Particularly in very dry climates, as well as installations over radiant heat, an engineered floor must be chosen carefully, and the home must have a humidification system that can maintain the floor at its required range. Some people say engineered flooring isn’t appropriate for certain climates, but I always ask: Do people in those areas have grand pianos or other musical instruments? Expensive woodwork? If you can have other high-end wood products/investments there, you can have an engineered wood floor, but you have to do what’s necessary to maintain it correctly.

Roy Reichow is founder of National Wood Floor Consultants in East Bethel, Minn., and is an NWFA Regional Instructor.

CARB

I’ve heard that engineered wood flooring is often made with formaldehyde and I should look for “CARB” flooring if I want low emissions. What does that mean?

A: The California Air Resource Board is a state agency that creates regulations governing everything from car exhaust to emissions from televisions. In the wood industry, both the agency and the specific regulations regarding formaldehyde emissions are commonly referred to by its acronym “CARB.”

Meeting CARB’s requirements is a legal must in California, but just because a flooring is not specifically marked as “CARB-compliant” doesn’t mean it has a dangerous level of emissions.

There are two factors that help make this confusing. First, flooring isn’t actually covered by CARB—you can’t have “certified” flooring. CARB applies to the cores used to make engineered flooring, the plywood and MDF, and, for flooring sold in the state of California, it is necessary to utilize CARB certified cores. However, as the second factor, there are two aspects to the CARB program—the emission level and the record keeping burden. Material can be produced to or under the emission levels, but still not be “CARBed” because documentary burdens aren’t being met.

So while looking for the CARB-compliant statement is a good indicator of a low formaldehyde emissions level, its absence is not an indicator of a problem. Overall the engineered flooring sold in the United States is extremely safe. However, consumers who are very conscious of indoor air quality and want a low-emitting product should look beyond CARB to products with a voluntary certification based on California Section 01350, a program that can check for emissions from up to ten thousand potential VOCs (although admittedly few would ever appear in wood flooring in the first place!). Certification programs based on CA 01350 include FloorScore, VOC Green and GreenGuard Gold.

Elizabeth Baldwin is environmental compliance officer at Metropolitan Hardwood Floors.

BALANCED

I hear people refer to “balanced” construction of engineered wood floors. What does that mean?

A: Of course there are many different ways to make an engineered wood floor, but having a “balanced” engineered wood floor is very important. Creating a balanced engineered floor involves understanding the variations in species, thickness of plies, and widths in order to create a product that doesn’t experience problems such as warping, crooks and bows.

For example, one way to create a balanced product is to have symmetry between the top layer and the bottom layer by using the same species and thickness of wood for both of those layers. Although engineered wood flooring is more stable than solid wood flooring, its wood layers do react to changes in moisture, and creating symmetry in those layers with the same species and the same thickness of material on the top and bottom reduces the tension created by moisture fluctuations.

Typically “balanced” products such as those described above have three layers, and the middle layer is usually done out of plywood or a softwood. Although this may seem like a cost-saving measure, the softwood in the middle (glued crosswise, at a 90-degree angle) actually increases the stability of the flooring, allowing the plank a bit of flexibility with less tension in the piece of flooring. Such construction can allow wider widths and longer lengths than would otherwise be typically possible.

Even when using a wood floor with a balanced construction, keep in mind that engineered floors will change with the environment. Using a humidifier can help improve the humidity level and decrease the gapping. As long as a flexible adhesive was used (for glue-down floors), the gaps will close again as soon as the humidity level increases. Remember that human beings and wood need the same climate to feel comfortable (our recommendations are about 45-55% room humidity and approximately 68 degrees Fahrenheit).

Florian Fillafer is CEO of Mafi America Inc.

WARRANTIES

I’ve heard many people complaining about the warranties that come with engineered flooring. Can you help me understand them?

A: Engineered wood flooring warranties, with all the technical wording that technical staff and lawyers build into them, are important to the consumer and are very important from a competitive viewpoint when consumers are making their decisions. From a marketing standpoint, as manufacturers, we fully understand the impact of the warranty.

However, I believe that engineered wood flooring warranties are often “over-sold” in our industry. Most of us in the industry have heard outrageous claims about what product warranties will do for the customer. Unfortunately, in some cases, there may be misleading or exaggerated statements that create the impression that the warranty will cover anything that goes wrong. More often than not when we hear from people with a problem, it’s a result of them having been over-sold and expecting “bullet proof.”

The consumer feels all warm and fuzzy when they make the purchase, and then they are often upset when they discover what the fine print says in most warranties. No one explains what the “limitations” of a “limited warranty” are, nor does the consumer bother to ask or read the warranty at all, even though it is often a significant factor in their purchase decision after being told by sales staff, “If anything goes wrong, the manufacturer will replace it.” Consumers have come to expect the same kind of service in hardwood flooring that they get on small retail purchases: immediate credit back on their card, no questions asked.

Most warranties have two main parts: the structural warranty and the finish warranty. The structural warranty guarantees that the floor won’t come apart, with exclusions for things like obvious maintenance problems, installation errors and site condition problems. A finish warranty usually guarantees the finish won’t wear through to bare wood, again, with exclusions for things such as high heels, pet claws, fridge casters, furniture legs, etc. (Note that finish may look worn before it wears through to bare wood.)

We work hard to make a quality product, and when the warranty is over-sold to the consumer, it reflects as a negative on our company, so we make a strong effort in our marketing materials to be as up front with the customer as possible. We realize that every manufacturer battles this issue, and it’s challenging when you can’t control all the consumer hears at the point of sale, what happens to the flooring after it leaves your mill, how it is installed or how it’s treated after installation by the homeowner.

Paul Stringer is vice president of sales and marketing at Somerset, Ky.-based Somerset Hardwood Flooring.

ACCLIMATION

How long do I need to acclimate my engineered hardwood flooring prior to installation?

A: Unlike the directions for solid products, many manufacturers of engineered wood flooring recommend that the flooring stay in its packaging until you are ready to install it. At the time the packaging is opened and installation is ready to begin, the job site should be at normal living conditions. The parameters for “normal living conditions” vary by manufacturer (ours are 68–78 degrees Fahrenheit and relative humidity between 35–55 percent; NWFA Installation Guidelines give a general recommendation of 60–80 degrees and 30–50 percent RH depending on the geographic region).

Brian Greenwell is VP of sales and marketing at Mullican Flooring in Johnson City, Tenn.

VENEER

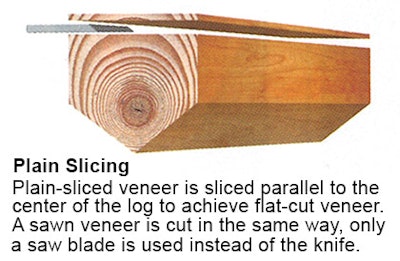

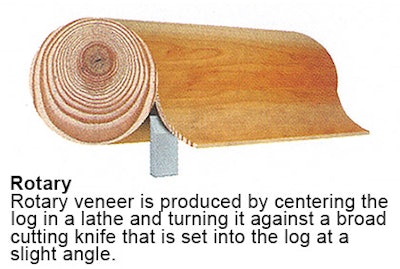

Can you explain the types of veneer that are used on an engineered wood floor and what they mean for the end user? A: For engineered flooring, there are three basic types of wear layers: sawn, sliced and peeled. A sawn face has lumber that is sawn into wafers and then glued onto a plywood core (the process is same as the one in the “slicing” illustration at right, only a saw blade is used instead of a knife). A sawn face has more the look of a solid floor but offers some of the stability of an engineered floor. Because it is typically a thicker face and products with sawn faces aren’t “balanced” (having the same product on the face and back layers), it can have some issues with cupping and other problems related to moisture and seasonal humidity fluctuations.

Next there are rotary-peeled faces. With this veneer, the layers of wood are peeled off the log on a rotary lathe. Typically you’ll have the same material on the face as on the back, and these products will have three or five plies and be very stable. Rotary peeled faces appear somewhat different from a solid floor—someone in the wood flooring business will be able to tell which is a rotary peeled floor and a sawn face, but the average consumer can’t do that. Then we have sliced faces. These combine the appearance of a solid wood floor with the technical improvements of a veneer. Sliced faces are cut in the same direction as a sawn face but are cut with a knife, so there is more yield out of the lumber and no sawdust. The greater yield makes these faces a little more environmentally efficient. However, you can’t slice this type of veneer as thick—at a certain thickness you have to saw the wood. Sliced veneers run from fairly thin ones (often used for furniture and architectural panels) of about 1/42 inch up to about 1/16 inch. When you get beyond that dimension you generally have to use sawn veneers. Today, I would say that how much wear layer you need depends on two things. First, how good is your finish? Today’s UV-cured aluminum oxide finishes aren’t going to wear out under normal circumstances, so if you have a good finish you don’t need as thick a wear surface. A sliced or peeled face floor will serve you well and give you some added stability benefits. Second, are you going to want to change the style of the floor? If you will want to change the color or the texture of the surface, you’ll need enough wood to sand it down, which generally leads you to a solid or sawn face floor. Don Finkell is CEO at Boca Raton, Fla.-based American OEM Wood Floors. |

Product Standards

While NWFA manages the standards for solid wood flooring with its NOFMA certification program, engineered wood flooring standards are handled by the Hardwood Plywood & Veneer Association. The standards can be ordered online for $25 at www.hpva.org. |