About 25 years ago, I came up with the idea of recreating Rembrandt van Rijn’s painting “The Night Watch.” However, for all those years, it remained just an idea. Since 1999, I have been a wood floor craftsman, and I have always enjoyed the creativity that comes with the trade. But after more than two decades in the profession, I felt I wasn’t using my creativity enough, so I set out to undertake a project that would truly challenge my artistic skills. That changed with the creation of the Annual Ring Floor, which won the WFB’s 2020 Best Commercial and Best Stairs Design Awards. That project proved to me that I was ready for a significant challenge in wood flooring, inspiring me to finally attempt “The Night Watch in Wood.”

Four years ago, I set out to create “The Night Watch.” A portion of Rembrandt’s painting was cut off centuries ago as it was deemed too large to hang, but I decided to restore those missing sections so that the work would once again be complete. My completed version in wood would measure nearly 4 by 5 meters (13 2/25 by 16⅖ feet) and be composed of 195,000 wooden pixels, each measuring 1 centimeter square (25/64 of an inch), crafted from 45 species and 52 colors.

Creating “The Night Watch” using hundreds of thousands of wood pixels would be a monumental undertaking, requiring significant financial resources and years to complete. To dedicate myself fully to this project, I decided to sell everything I owned, including my house, and move into a small apartment to raise funds. Parketfabriek Lieverdink and Amsterdamsche Fijnhout supplied the wood, “De Bouwmaat” followed and published the entire process in their magazine, and Bona Sweden supported the project with financial contributions, products and technical expertise.

Mapping ‘The Night Watch’

Initially, it was challenging to know where to begin, as this type of project had never been attempted before. There was no blueprint for transforming a painting into a wooden re-creation.

The objective was to use different species of wood, untreated, to match each color in “The Night Watch.” When I first set out to create it out of tiny wooden pixels, I thought I could estimate the colors of the painting myself and choose the matching woods, but I realized that would take too long and the colors wouldn’t be accurate to the painting. “The Night Watch” contains hundreds, maybe even thousands of shades: from nearly black backgrounds to many brown tones that make it difficult to find a wood species that matches each tone in the painting. And Rembrandt plays with light and shadow; it would have been impossible to do the color coordination manually.

I progressed to a more complex project and enlisted the help of computer science student Senne Weda to develop an RGB color system. His system assigned a hex code to each species of wood, matching these codes with colors that most closely correspond with colors in the painting. Senne then created a digital blueprint detailing where each species and color should be placed in the artwork, resembling a paint-by-numbers layout.

The system had its limitations since wood species can vary in shade and structure from one segment of the tree to another, which means you can’t assign them a fixed RGB value. Additionally, there are no wood species that perfectly match every color in the painting, so we had to do our best to find the closest color matches possible. For black, we used wenge and for white, we used maple. Truly white wood doesn’t exist, but we came as close as possible.

The design and technical development for “The Night Watch in Wood” took about two and a half years.

Cutting the Pieces

After selecting all the species and creating the map, I began cutting the pixels.

Forty-five species were selected, but some were chemically altered to achieve the desired color, resulting in 52 variations. The completed “Night Watch in Wood” consists of 195,000 wooden pixels, but I likely cut around 250,000 pixels over many months to have enough in reserve. Although I received help with design and assembly, I wanted to cut every pixel myself with a Festool CS 50 saw because it required both skill and feeling. This was essential because the 1-by-1-centimeter blocks needed to be cut with precision.

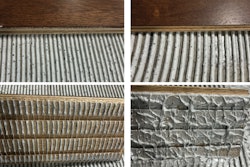

Each piece of wood was cut diagonally across the grain to give the pixels extra strength and texture. The wood was initially cut into strips 1 centimeter wide, and then each centimeter cube was cut from the strip.

The strips were taped on both the front and back to keep the blocks from falling out during cutting. After that, I—with the help of Regius College Schagen students—spent hours removing the pixels and sorting them by wood species into bins.

Creating the Panels

If all the pixels had been fixed together, “The Night Watch in Wood” would be unmovable because it would be extremely heavy. So, to allow the piece to travel to different locations once it was finished, the work had to be modular and transportable.

Senne’s gridded map was glued onto plywood panels, then each pixel was glued to the grid and plywood to form a sturdy panel. Each panel measured 20 by 20 centimeters and contained 400 pixels. There were 500 small panels created. Next, 25 of the small panels were tongue and grooved together with another backing to create 20 movable pieces of “The Night Watch in Wood.” To keep the panels secure when displayed, a wooden frame was built.

We worked with Bona to develop a transparent silane glue for securing the pixels to the panels. The glue had to be transparent because any color that came up between the pixels would distort the image.

Testing the Colors

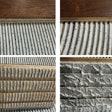

After a year of gluing and assembling the 195,000 pixels, each panel was moistened with water to bring the colors to life. The panels were then photographed and digitally combined in Photoshop. Only then could we assess whether the work matched Rembrandt’s painting and where corrections were needed.

It turned out that the mahogany pixels were too light and too flat in texture. As a result, the whole work didn’t look right. Using Senne’s system, we isolated the mahogany pixels, after which I had to replace them one by one.

Over 17,000 pixels—around 9% of the piece— needed to be replaced. Using a projector, we marked each mahogany pixel with a white marker and routed it out. Next, we needed to find a species that matched the required color to replace the mahogany. It couldn’t be too similar to other wood species we were using, or the pieces would blend together. We ended up using a mixture of smoked, steamed and baked oak.

We couldn’t have predicted that the mahogany wouldn’t work from the beginning, as the whole work had to come together before we could assess if it matched Rembrandt’s work. It was a whole visual process to see that the mahogany needed to be replaced by three different species.

This was the hardest and most irritating part of the project, as it took another three months of work.

Once all the replaced pieces were added and “The Night Watch in Wood” was fully assembled, I buffed the work with Bona fiberpads and waterpopped the floor before applying the oil finish.

From Vision to Reality

The project took four years to create, with two and a half years of preparation, hundreds of hours of cutting and gluing wood, and countless people who believed in the work and made it happen. There were also countless side tasks that kept me quite busy: from marketing and communication to partnerships, from management and planning to education and guiding students—necessary tasks, but ones that demand a lot of energy on top of creating the artwork. Applying the final layer of oil over “The Night Watch in Wood,” once everything was finished, made all the years of work and the dreaded replacement of the pixels worth it.

“The Night Watch in Wood” made its first public appearance at the WorldSkills final in Amsterdam on March 20. My goal is to take the work around the world, including the United States, so people can walk on it, stand on it and use it as a stage for dance, theater, music or even a TED Talk. What do you want to tell? What do you want to show the world? I would love to bring “The Night Watch in Wood” to the U.S. If there are people who can help me bring it there, I would be happy to get in touch at info@ dutchwoodartist.com.

SUPPLIERS: Adhesive, Buffer, Finish: Bona | Saw: Festool | Wood flooring: Parketfabriek Lieverdink, Amsterdamsche Fijnhout