Quite awhile back, another contractor and I were chatting, and he said something that still rings in my ears. When commenting on a trivial operation during the course of the day he said, "If I have to stop and pick it up, I'm losing money!" It doesn't really matter what the operation was, but the spirit of his comment was that he knew where his profit margin was, and stopping the continuity of the job seemed to threaten that. When I asked what percentage profit margin he operated at, however, he had no idea. He relied on intuition, and if he "felt" like he was making a profit, he was.

I called BS, and he resisted, continuing to say that the task (of picking "it" up) would've slowed him down and caused him to lose money on a per-hour basis.

I let him have his opinion and moved on, but I never forgot about that. Part of me wondered if maybe that is the way it's done. Was it normal everyday business?

In my own tiny business, I have evolved to structure my quotes using Excel, and I formed a template customized to my liking. As I add in materials and labor to the template, I mark up EVERYTHING. Nothing is for free. Well, maybe something in the spirit of "exceeding expectations," but that's the limit.

But how do you "mark up?" And is markup the same as "gross profit margin" or "profit," for that matter? If you're running a business, you need to understand what they mean and how they work in your own company.

Defining profit, margin and markup

All three are different. In simple terms, any amount of money left over after you deduct all your expenses—including your overhead—is profit. And your cost divided by your selling price is the profit margin. You need to know what your expenses are and what your goal is for your profit margin in order to figure out the correct markup. In my business I like to keep my operating profit margin at 30%.

How it works in real life

For the purposes of making the math easy, let's say an order of flooring is $1,000 and you want to add a 30% gross profit margin. You would add $300 to $1,000, right?

Not quite—that only yields a 23.07% profit margin. Adding $300 is a 30% markup, not your profit margin. To get profit margin, you divide your cost by the selling price and subtract that number from 1:

$1,000 / $1,300 = 0.7692

1 – 0.7692 = 23.07% profit margin

To get to our 30% profit margin, the markup would have to be $428.57—a markup of 42.8%—for a total price of $1,428.57. You can check this by dividing your cost by the selling price:

$1,000 / $1,428.57 = 0.70

1 – 0.70 = 30% profit margin.

This is important because your sales have to cover your operating costs. Sometimes we "guess" at where to land in our bids, but with this simple strategy, you can be as accurate as a Stealth missile.

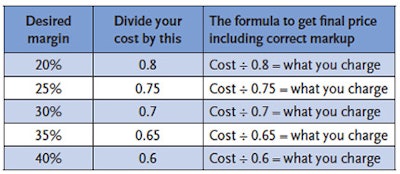

Easily figuring out markup

Let me offer this handy way to figure out markup without using a Brainiac Super Computer—with a handy dandy table. Note that the smaller numbers are there for instructional purposes, try NOT to use them.

My fellow pro Dax Williams told me his dad, Robert Williams, taught him that "30% pays the bills and 40% buys the toys." I would offer that that is true as long as you can acquire consistent sales and back it up with exceptional service. When you charge more, customers demand more! So be ready to ramp it up if this is what you aim for.

Let's do some real-life examples (assuming we're at my 30% profit margin):

Subtract your 30% (expressed as a decimal, 0.3) from 1 and divide your cost by that number. So:

1 - 0.30 = 0.70

$1,000 / 0.70 = $1,428.57

To get a 34.97% profit margin, for example, you would subtract 0.3497 from 1, which equals 0.6503. Then you would divide $1,000 by 0.6503 to get a price of $1,537.75. I know that's a zany number, but you can aim for any zany number if you know how.

Now you know what to accept and reject

See, if you know your desired profit margin, you can figure out what price to quote, and then you'll also know what price to reject. Giving away too much free stuff or saying, "I'll do it; I really NEED the money," can be a really bad move. I have heard some of my competitors say, "It's just cash flow" as if that's a good reason—it's not. Sometimes it's just better to reject a low-ball counter-offer and go watch Oprah on TV than to really do the job and lose money!

By the way, this is planning on everything going right. If some small thing goes wrong, you can be in the red, left wondering how you got there when you thought the quote looked so good on paper. Real-life examples include giving away a free re-coat, or free shoe molding, or free reducers, or maybe—God forbid—a free living room refinish that wasn't even on the quote (yes, I did that on a job in West Los Angeles in 1995).

RELATED: Thorough Estimates Can Prevent Job-Site Problems for Contractors

The ol' adding-$1-per-foot method

Let's take a look at the age-old "add $1 to the cost of the materials" trick. That may work out just fine for a $0.89-per-square-foot product, like an 8-mm laminate, but what happens when you have an $8 plank—or higher?

Here's how it calcs out. The selling price for the laminate ($1 + $0.89 = $1.89) would yield a 53% profit margin, while the $8 product (selling for $9) yields only a 11% profit margin. So, as costs change, the "adding $1 trick" fails you—big time.

Does this make you afraid?

I want to pull the car over here for a moment.

If you have plank that costs you $8 per square foot, don't be afraid to charge your customer $11.43 per square foot for it. Heck, I'd round it up to $11.50 so it looks cleaner. Regardless, the thought I want to share is this: Don't be afraid to charge what most customers are already expecting to pay. Of course, some customers will barter on this. Stay resolute. We are entitled to a fair profit, and 30% is a fair profit.

Pulling back out on the road now …

Combating the counter-offer

Suppose you know your labor, materials and overhead cost you $1,000, and you don't know what price to quote the customer. From the example above, based on my business costs, I'd charge $1,428.57, which enables you to pocket a 30% profit margin. Then, your customer comes back and says, "You are too high, let's make a deal at an even $1,200." This is where you not only know that is too low, but you know why it is too low. The counter-offer of $1,200 gives you only 16.67% profit margin ($1,000 divided by $1,200 = 0.833 subtracted from 1 = 16.67%). You tell the customer that won't work, and you've dodged a bullet. If the customer says the next contractor bid the job at that price, than you can know that other contractor is going to end up losing money, even if the job finishes on time with no problems. The other contractor is only making a 16.67% profit, and if even the slightest thing goes wrong, he'll be in big trouble. Plus, he's not going to have enough money to pay his payroll taxes and workers comp premium. The joke's on that guy!

By the way, just to be clear, the 0.833 above is the percentage of how much labor and materials and overhead—your costs—make up of the quote. The amount from 0.833 to 1.00 is your 16.7% profit. It's not much in this example, but the math works out as the job costs climb higher.

What happens when things take too long

Let's go through one more example.

Let's say you sold the job for $1,428.57 and that, to use an easy number, you figure 10% of sales is what your budgeted cost is for labor—in this example, $142.85. At $25 per hour, the job MUST be completed in 5.71 hours (142.85 divided by 25) for you to put your forecasted 30% profit in your pocket. If your employee worked an eight-hour day, you've lost your profit margin. This is what "milking" hours looks like when it gets to your paycheck as the owner of your own business. (On a side note, paying your employees by piece work eliminates "milking" the job for hours, but that is a topic for another article.)

The numbers in all these examples are small so it's easier to understand the logic. Of course, with bigger jobs, the math is exactly the same. Most of us are independent business owners who wear many hats, including everything from selling the job to chasing the money. Knowing your markup and profit margin is another essential hat. You may be the absolute master at installing a herringbone parquet down an S-curved hallway, but if you don't charge the right amount for that epic install, you're going to be seeking a job at Walmart as a greeter sooner rather than later.

In the end, we want enough extra to treat our spouses and children right and save to actually have a retirement. This is how it happens. I hope you make bank on each and every job you do. It's our right, and we work hard to make it happen.

See more from Angelo DeSanto:

A Distinction I Never Wanted: Being Expensive

How I Stand Up to GCs to Get Paid Quickly

Can You Be King of the Hill in Your Wood Flooring Market?

A Wood Floor Pro’s Rant: Post-It Notes and Slow-Pay Customers

See all of Angelo DeSanto's popular blog posts and magazine articles here.